This post was originally published on this site

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Beating the market is so difficult that you’d be excused for giving up.

But unlike what happens when you give up elsewhere in life, in the investment arena it’s actually a shrewd strategy for winning. Overconfidence, on the other hand, is one of investors’ biggest pitfalls.

After more than 40 years of rigorously auditing the performance of investment advisers, I have learned that over the long term, buying and holding an index fund that tracks the S&P 500

SPX,

or other broad index nearly always comes out ahead of all other attempts to do better, such as market timing or picking particular stocks, ETFs and mutual funds.

It’s amazing when you think about it: What other pursuit in life is there in which you can come close to winning every race by simply sitting on your hands and doing nothing?

I’m not saying it’s impossible to beat the market. What I am saying is that it’s very difficult and rare. And it’s even rarer for an adviser who beats the market in one period to do so in the successive period as well.

I am not the first person to point this out. But what I can contribute to the debate is my extensive performance database that contains real-world returns back to 1980. It compellingly shows how impossibly low your odds are of winning when trying to beat the market.

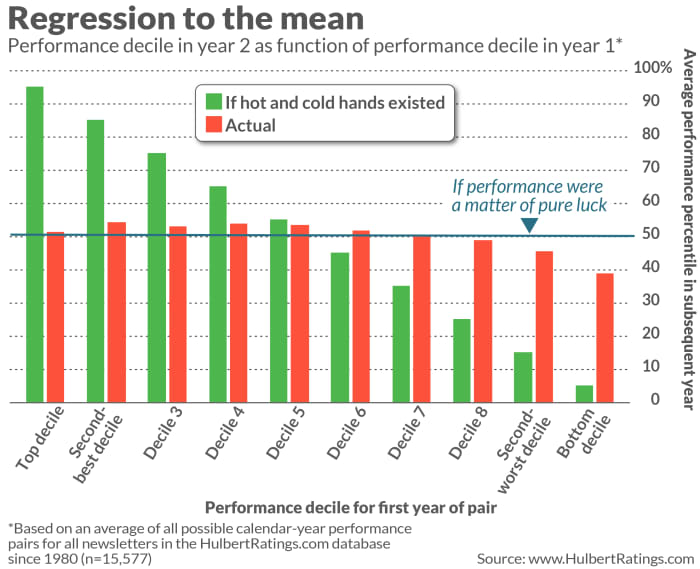

My first step in drawing investment lessons from my huge database was to construct a list of investment newsletter portfolios that at any point since 1980 were in the top 10% for performance in a given calendar year. Given how many newsletters my Hulbert Financial Digest has monitored over the years, this list of top decile performers was sizable, containing more than 1,500 portfolios. By construction, the percentiles of their performance rank all fell between 90 and 100, and averaged 95.

What I wanted to measure was how these newsletter portfolios performed in the immediately succeeding year. If performance were a matter of pure skill, then we’d expect that they would have been in the top decile for performance in that second year as well—with an average percentile rank that also was 95.

That’s not what I found, however—not by a long shot. These newsletters’ average percentile rank in that second year was just 51.5. That is statistically similar to the 50.0 it would have been if performance were a matter of pure luck.

I next repeated this analysis for each of the other nine deciles for initial-year performance rank. As you can see from this chart, their expected ranks in the successive years were very close to the 50th percentile, regardless of their performance in the initial year.

The only exception came for newsletters in the bottom 10% for first-year return. The average second-year percentile ranking was 38.8—significantly below what you’d expect if performance were a matter of pure luck. In other words, it’s a decent bet that one year’s worst adviser will have a below-average performance in the subsequent year too.

What these results mean: While investment advisory performance is not a matter of pure randomness, the deviations from randomness primarily occur among the worst performers—not the best. Unfortunately that doesn’t help us to beat the market.

By the way, don’t think that you can wriggle out from these conclusions by arguing that other kinds of advisers are better than newsletter editors. At least in regards to the persistence (or lack thereof) between past and future performance, newsletter editors are no different than managers of mutual funds, ETFs, hedge funds and private-equity funds.

How to become a better investor: Sign up for MarketWatch newsletters here

Beware of arrogance

While I believe the data are conclusive, I’m not holding my breath that it will persuade many of you to throw in the towel and go with an index fund. That’s because the typical investor all too often believes that the poor odds of beating the market apply to everyone else but not to him individually.

It reminds me of the famous study in which almost all of us indicate we’re better-than-average drivers.

This arrogance has obviously dangerous consequences on our roads and highways. But it’s dangerous in the investment arena as well because it leads investors into incurring greater and greater risks.

That creates a downward spiral: When the arrogant investor starts losing to the market, which inevitably happens sooner or later, he pursues an even riskier strategy to make up for his prior loss. That in turn invariably leads him to suffer even greater losses. And the cycle repeats.

The temptation of arrogance is particularly evident when it comes to social media. Psychologists have found that younger investors are far more inclined to pursue risky strategies when they are being watched than when operating alone. This helps to explain the bravado that so frequently is exhibited on investment-focused social media platforms.

Buying and holding an index fund is boring. Adherents are rarely drawn to social media in the first place, and even if they are, they rarely post that they are continuing to hold the same investment they’ve had for years.

Beware of this trick, too

A similar dynamic leads those who frequent social media to brag about their spectacular winners while ignoring their losers. One frequent way they do it is to annualize their returns from a short-term trade and then boast about that figure. Imagine a stock that goes from $10 to $11 in a week’s time. In itself, that doesn’t seem particularly remarkable. On an annualized basis, however, that is equivalent to a gain of more than 14,000%.

Readers of these social media boasts initially must believe they are the only ones with a mixture of both winning and losing trades. Only later do they discover the unspoken rules of social media platforms: it’s bad form to ask fellow investors about their losers, just like it’s poor etiquette after a round of golf to ask the boastful golfer whether he actually beat par.

Humility is a virtue in the investment area. We would do well to remember Socrates’ famous line: “I am the wisest man alive, for I know one thing, and that is that I know nothing.”

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.