This post was originally published on this site

Record demand for the Federal Reserve’s overnight reverse repo program could touch a new milestone of $1.4 trillion by year’s end, says Barclays rates strategist Joseph Abate.

That’s mainly because he sees demand for the facility climbing if debt-ceiling negotiations in Washington drag out through the fall, which could cause the already dwindling supply of Treasury bills to shrink even further.

“How high will balances in the RRP get?” Abate asked, referring to short-term use of the Fed’s reverse repo program, in a Monday note. “We expect the RRP to reach $1.4trn over the next 3 months as debt ceiling reduces bill issuance.”

Abate earlier in August dubbed the Fed’s reverse repo program a “replacement bill provider” to the U.S. Treasury, calling it a key alternative for cash investors who might otherwise keep their liquidity in bills.

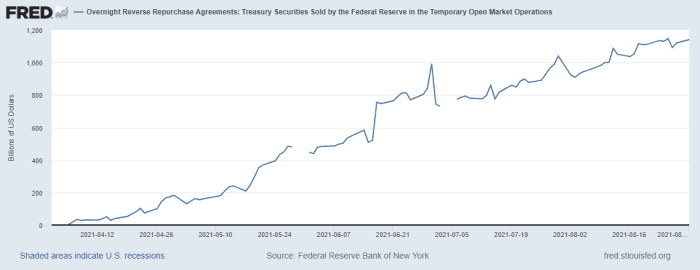

Demand for the facility has climbed since April, as low global rates and trillions of dollars’ worth of pandemic stimulus have washed through financial markets.

Demand for Fed facility tops $1 trillion and counting

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

The overnight Fed program has been a haven for money-market funds and other financial firms looking to park the flood of cash sloshing through the financial system overnight, while retaining its value.

Use of the facility neared $1 trillion for the first time in June, after the central bank increased the rate it paid to users to 5 basis points from zero, as part of its effort to keep short-term rates in the Fed’s target range of 0% to 0.25%.

Now the facility might also be needed to keep markets from going haywire if Congress doesn’t act to raise or suspend the debt limit before time runs out over the next few months.

The big reason? After dwindling all year, the Treasury-bill market has shrunk by nearly $850 billion, a figure Abate expects to contract by another roughly $300 billion as prolonged debt-ceiling talks force the Treasury to spend down its cash account and trim bill issuance.

“To settle its coupons, given the binding constraint of the debt ceiling, the Treasury could need to cut bill supply further this summer,” he wrote.

By the end of July, when the debt-ceiling suspension expired, the Treasury had about $459 billion in cash at the Fed, according to Abate, who expects the Treasury to have enough cash and borrowing capacity to operate normally through the end of October.

Stock investors mostly have shrugged off concerns about the debt-ceiling impasse, with the S&P 500 index

SPX,

and Nasdaq Composite Index

COMP,

both extending further into record territory on Monday, as the 10-year Treasury yield

TMUBMUSD10Y,

edged below 1.3%.

But without a debt-ceiling deal soon, nervousness could build this fall around potential bill repayment delays. Abate thinks that could cause more money to be pushed into the Fed’s overnight repo facility, lifting it to a roughly $1.4 trillion milestone.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen in early August told congressional leaders that her department began taking extra steps to avoid default, while also urging Congress to act “as soon as possible” on the borrowing limit.

A group of Republican senators in mid-August signed a pledge to force Democrats to increase the debt ceiling to avoid a U.S. default, but without GOP votes.

Until a deal happens, the Fed facility might serve as a stabilizing force. Specifically, the Fed several months ago increased the cap on how much each counterparty could park overnight in the reverse repo facility to $80 billion, but those caps haven’t come close to being tapped out.

Abate estimated that money funds, a key of the overnight program, were using only about 25% of available RRP capacity, while serving as a broader stabilizing force for markets.

“In addition to meeting money funds’ unmet bill demand, the RRP has helped to put a floor under all market rates,” Abate wrote, adding that 3-month Treasury bills have traded to close to the RRP rate since it was bumped up to 5 basis points.

But even in the event Washington ends up reaching a debt-ceiling agreement by October, demand for the Fed’s overnight program won’t suddenly end, said John Canavan, a lead analyst at Oxford Economics.

“The Treasury bill and Treasury cash-balance issues should only partially reverse in Q4,” Canavan wrote in a Friday note. Specifically, if the Fed starts to taper its $120 billion a month in asset purchases this year, he still expects it to take eight months for the large-scale asset purchases to wind down, a stretch that would continue to add liquidity to markets.

After that, “any decision to shrink their balance sheet and remove liquidity will remain a long way off,” he wrote.