This post was originally published on this site

Savvy cash management, or creative bookkeeping?

The City of Chicago recently announced plans to use funds from the federal American Rescue Plan stimulus to pay down about $500 million in short-term debt it took out in December. The step received scant attention until a public-finance expert published a blog post on the subject in August.

As Amanda Kass, associate director for the Chicago-based Government Finance Research Center, makes clear, the move isn’t improper — but she thinks it isn’t a prudent selection of all the possible steps either. At best, Kass sees it as a financial Hail Mary that will probably work out for the city, at the expense of transparency and public engagement.

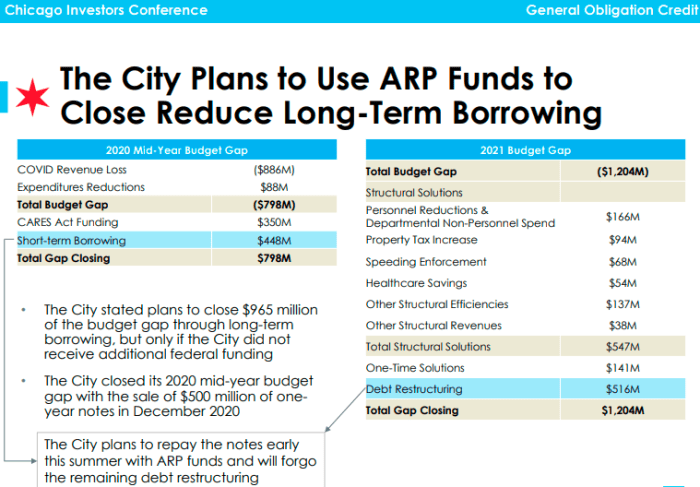

Here’s what happened. Last November, facing a near $800 billion fiscal year 2020 budget gap, due mostly to the pandemic, city managers decided to borrow $450 million in short-term debt, plus interest. City managers reached out to several banks and found JP Morgan offered the best rate. The deal was finalized in December.

The one-year credit line offered a few advantages. Most notably, it bought the city time to see if more fiscal stimulus money would become available.

But it brought some pitfalls, as well. Among them: doing what’s often called a “private placement” with a bank is a known method for letting a municipal entity avoid the scrutiny and public input that comes from issuing bonds into the market. What’s more, the American Rescue Plan funds are not meant to be used to pay down debt, although using them to plug budget holes from lost revenue is allowed.

Finally, the credit line simply represents an uncomfortable maneuver: state and local governments aren’t supposed to borrow to keep their budgets balanced. While many use lines of credit or short-term debt (often called Revenue Anticipation Notes), those are primarily for expected, ongoing revenues that just happen to be lumpy throughout the fiscal year, leaving certain periods of time with no money coming in to support ongoing spending.

As Chicago officials put it in a May presentation to investors, “The City stated plans to close $965 million of the budget gap through long-term borrowing, but only if the City did not receive additional federal funding. The City closed its 2020 mid-year budget gap with the sale of $500 million of one year notes in December 2020. The City plans to repay the notes early this summer with ARP funds and will forgo the remaining debt restructuring.”

Source: May Chicago Investor Conference

The city did not respond to a MarketWatch request for comment.

Related: The Fed’s COVID-era municipal lending program worked for Illinois

“I do think this fits the spirit of the American Rescue Plan program,” Kass told MarketWatch. What she finds troubling is the lack of transparency. In the May investor presentation, city officials referenced an earlier statement about its intentions for the short-term financing, but any such communications proved impossible to track down. (Some publications, including the municipal-market industry standard The Bond Buyer, reported it.)

Also, as Kass put it, “the discourse used to explain the plans is largely directed at the municipal bond market, including credit rating agencies, bank underwriters, and investors.”

More to the point, Kass said, “I think there can be a policy and political debate about the choices here. Should we be using (Rescue Plan funds) for restoring revenue, maintaining current operations, or direct spending programs like rent relief or utility relief?”

Also unclear, she said, is what the city’s Plan B might have been if no additional stimulus had been approved by Washington. In the May investor presentation, officials note that they were prepared to borrow longer-term debt if that had happened — paying more in interest and making an overly indebted situation even worse. What they don’t say is what the tradeoff would have been if that were the case, Kass pointed out.

“Who would have been impacted by spending cuts?” she said. “I don’t see how this relates to city programs and services and communities that are maybe most in need of the city’s attention or have been neglected. I don’t see it connected to the policy decisions that the mayor has stated are priorities. It seems stark to me at a moment when there is so much need.”

Read next: Climate risk is hitting home for state and local governments