This post was originally published on this site

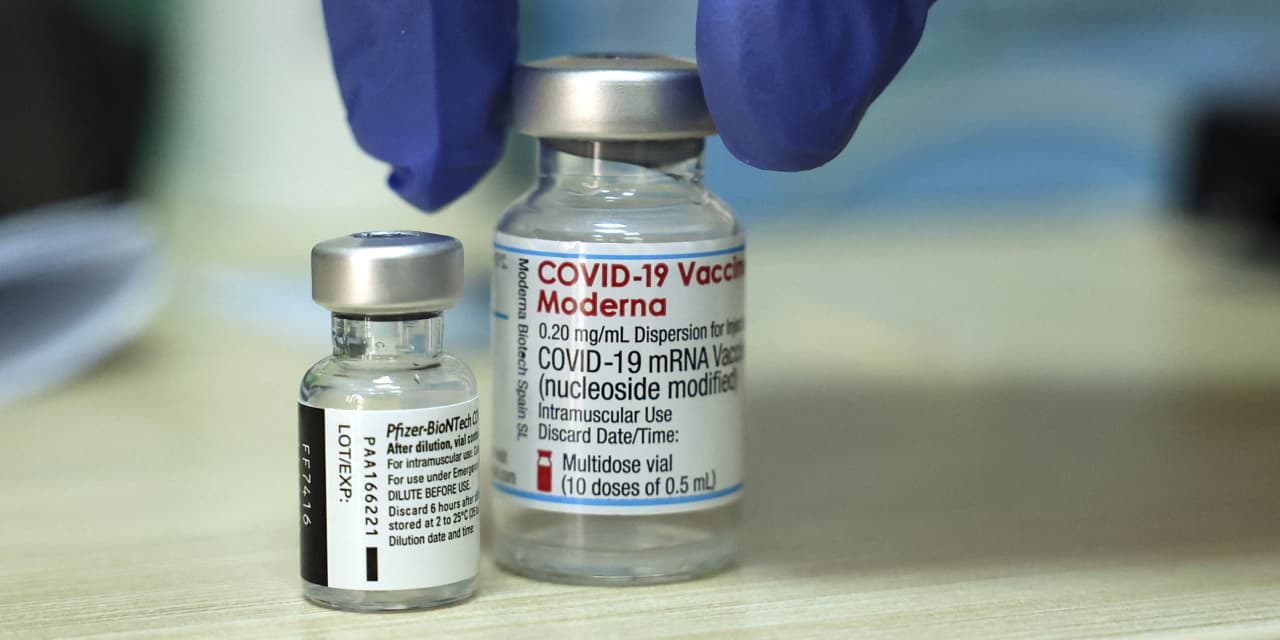

The decision to give out extra doses of Moderna and Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccines pits federal health officials who say the shots may not protect people from severe disease in the future against the public-health experts who disagree with their logic.

“It just doesn’t make sense on the surface,” said Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “This whole effort of giving a third dose will, frankly, do little to get us on top of this pandemic because the issue here is not boosting the vaccinated. The issue is vaccinating the unvaccinated.”

The majority of COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths are occurring in people who are unvaccinated. Only about 60% of the U.S. population who qualify for a shot are fully immunized, though vaccination rates are increasing.

However, federal health officials, citing concerns about waning immunity, announced last Wednesday that the Biden administration plans to allow adults in the U.S. who are fully vaccinated with the mRNA vaccines developed by Moderna Inc. MRNA or Pfizer Inc. PFE and partner BioNTech SE

BNTX,

to get a third dose starting Sept. 20 with a few caveats.

“

“I don’t think it’s true that just because you start to see fading of immunity defined as increasing incidence of asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic disease that therefore means the [waning] protection against serious illnesses is right around the corner. It could be three years from now. It could be four years from now.”

”

The extra dose must be administered at least eight months after the second shot, only to those age 18 and older, and will likely be made available first to higher-risk people, including residents of nursing homes and healthcare workers or those who were vaccinated back in December and January.

The White House’s plan appears to be dependent on authorization from the Food and Drug Administration, a recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, and a stamp of approval from the CDC itself. (These steps are part of the normal process of bringing vaccines to Americans during the pandemic.)

That said, how the plan was announced and the rationale behind the decision has perplexed some infectious-disease physicians.

Telling Americans about a plan before the FDA or the CDC have weighed in makes it seem like a “political decision, as opposed to a scientific decision that is being made by the appropriate regulatory agencies,” said Dr. Céline Gounder, an infectious disease specialist and epidemiologist for the NYU Grossman School of Medicine who was a member of President Biden’s COVID-19 Advisory Board. “The process doesn’t feel like it’s being followed.”

Beyond the optics of the announcement, Gounder and other experts have questioned the science used to back the decision.

Health officials cited three studies that showed breakthrough infections are increasing but the risk of hospitalization and death among the vaccinated remains low. But in their public comments, they hinted at a different set of worries for the future.

“We are concerned that the current strong protection against severe infection, hospitalization and death could decrease in the months ahead,” CDC director Dr. Rochelle Walensky said Wednesday.

The experts interviewed for this story say it’s not a logical leap to begin offering boosters now because protection against hospitalization and death could decline in the future. Traditionally, science and data lead the decision making in medicine. (That said, no one disputes that the vaccines are less effective against the delta variant, which is thought to make up nearly all cases in the U.S.)

“I don’t think it’s true that just because you start to see fading of immunity defined as increasing incidence of asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic disease that therefore means the [waning] protection against serious illnesses is right around the corner,” Offit said. “It could be three years from now. It could be four years from now.”

This is why Offit viewed the highly publicized data that came out of the outbreak in Provincetown, Mass., as a good thing. His take? No one died, only four vaccinated people were hospitalized, and most of the roughly 450 infections were mild or moderate.

“The goal has always been to prevent serious illness, to keep people out of the hospital, to keep them out of the ICU, to keep them from dying,” Offit said.

A changing stance on COVID-19 booster shots

The White House’s U-turn on booster shots is frustrating to many, in part because officials came out against them so strongly up through the second week of August.

Six weeks ago, the CDC and FDA said COVID-19 booster shots were unnecessary; Dr. Anthony Fauci, Biden’s chief medical advisor, said the same thing then, as did National Institutes of Health director Dr. Francis Collins.

Then, a week ago, officials said some people with weak immune systems, like organ-transplant patients, will be allowed to get a third dose but the general public did not need one. “Other individuals who are fully vaccinated are adequately protected and do not need an additional dose of COVID-19 vaccine at this time,” FDA acting commissioner Janet Woodcock said Aug. 12.

The following day, the CDC’s Dr. Kathleen Dooling said that while certain immunocompromised people may need a booster, “other fully vaccinated individuals do not need an additional dose right now, according to presentation slides.

This all changed with Wednesday’s announcement.

For Gounder, it makes a lot of sense to also give an extra shot to people who are older than 80 and those who live in nursing homes. These are individuals who are less likely to have robust immune systems and breakthrough infections for them are more likely to mean severe disease and possibly hospitalization.

In addition, giving an extra dose to someone who is immunocompromised is a different strategy than “boosting” the general population, in part because some of those individuals never mounted an immune response at all with the first two doses, Gounder said. In some of these cases, the third dose only helped some but not all of those types of patients develop an antibody response.

“Those three groups, I think there’s good evidence to giving extra doses,” she said. “It’s when you start to look at the rest of the population that it’s not clear.”

That’s why both Gounder and Offit say that the best value for the COVID-19 vaccines is making sure they get to people who are unvaccinated and unprotected against the delta variant.

“If you look at communities that have high vaccine rates, they have very low disease rates and areas that have low vaccine rates have very high disease [rates],” Offit said. “The vaccine is working. It doesn’t work if you don’t get it.”

Read the studies that informed the CDC’s decision for booster shots: