This post was originally published on this site

This article is reprinted by permission from NextAvenue.org.

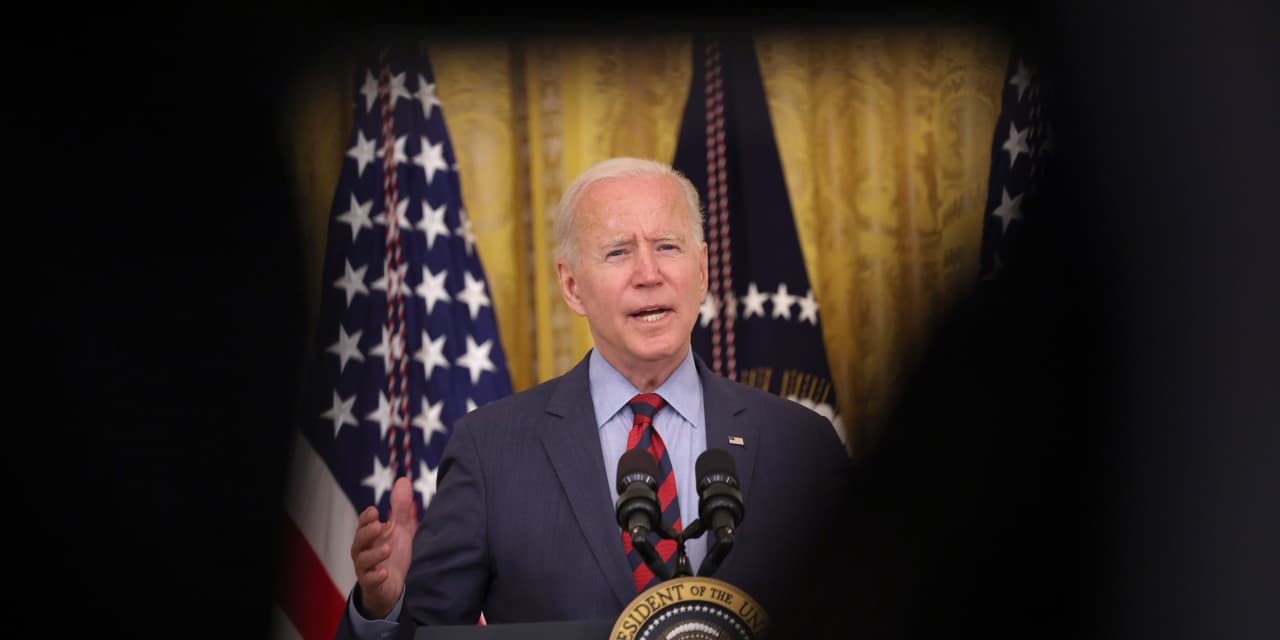

I would like to see the Biden administration take a bigger and bolder approach to aging — planning for the long term and not just the next four to eight years in office. In the same way that President Joe Biden appointed John Kerry as a presidential envoy to lead the fight against climate change, I believe there should be a presidential envoy to head up the administration’s efforts related to aging, longevity and retirement security.

A lot has changed since the Older Americans Act, the centerpiece of U.S. aging policy, was enacted in 1965.

Back then, life expectancy from birth in the U.S. was about 70 and the median retirement age was 65. Old-age policy focused on aging mainly as a time of functional limitation, frailty and dependence. It was about how best to care for people in their relatively short retirement years. At 65, you likely kissed your grandkids, did a little fishing or golf, collected your monthly Social Security benefit and were dead within five years.

Aging policy needs to reflect our longer lives

Today, thanks to advances in science, public health and technology, many Americans are living longer, fitter lives. A 60-year-old in reasonably good health has a 50% chance of living into their 90s. Current life expectancy is about 79, and there’s a good chance it will approach 100 in coming years.

And the older American population is not only enormous, it’s growing. By 2030, the number of adults over 65 will outnumber children under 18.

But with pensions fast becoming a relic of the past and real wages flat or falling for decades, millions of older adults have been too strapped to save. According to The New School Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis, the median retirement savings for middle-income people 55 to 64 is only $60,000. Financing a long life with meager resources to cover even basic expenses is a national problem that looks only to worsen.

The coming seismic demographic shift will have profound implications for nearly every sector of society. It is already evident in the labor market, where nearly a quarter of the U.S. workforce is currently 55 and older, a cohort projected to increase to one-third in the next decade.

So, while longer life is a game changer, old-age policy can seem, well, stuck in a 1965 time warp.

We need a national envoy with an overview of a new paradigm on aging that seeks to maximize the benefits of longevity through a life course approach.

Even taking genetics into account, the aging process is, to a degree, malleable and adaptive, influenced by a variety of exogenous factors throughout one’s life — including public health, environment and behavior. A growing body of research shows that our experiences in early life are important determinants of health and well-being in later life.

Our rate and manner of aging is different from our parents and grandparents and will continue to change. “Old” in the future may well not look like the “old” of today, as science and technology are able to prevent or postpone age-related functional decline and some chronic diseases.

A longevity agenda under this scenario is a potential asset to be harnessed for the nation. It offers an opportunity for people of all ages to maintain their physical and cognitive abilities and to remain independent, healthy and productive longer.

What a presidential envoy could do

Although we do have an Assistant Secretary for Aging who is the acting administrator at the federal Administration for Community Living, or ACL, (Alison Barkoff), that’s a job with a somewhat narrow focus: maximizing the independence, well-being and health of older adults, people with disabilities across the lifespan and their families and caregivers.

Appointing a presidential envoy on aging, longevity, and retirement security would send a powerful signal about the need to fundamentally change the paradigm on aging and speak to the urgency of grappling with the new challenges and opportunities of a rapidly aging U.S. population. It would make longevity — with all its implications for labor markets, financial markets, the health care system, housing, transportation and education — a front burner issue elevated to the highest strata of government.

Retirement experts like Prof. Teresa Ghilarducci and Next Avenue writer Chris Farrell have recommended an Older Workers Bureau within the U.S. Department of Labor. That would be useful, for sure, but I fear is too small a response.

Longevity is a grand challenge up there with climate change and requires an all-of-government approach for Americans of all ages.

The outdated view of older adults as mainly passive recipients of government benefits can lead to policies that focus mainly on meeting the special needs of people over 65 with declining abilities, leaving behind millions who are still active but also need policies and programs customized to their challenges.

Take a look at the president’s American Jobs Plan. Its bold promise to invest in multiple sectors of the economy to stimulate economic growth and create jobs could be hugely helpful for older Americans who need, or want, to work. Yet in the initial high-level outline of the plan, older adults are mentioned only once — as “aging relatives” in the section on the care economy. Experience has shown if older workers are not specifically targeted for services there’s a good chance they will be overlooked.

Read: This state sees age as an asset and wants to put older residents to work

The plan’s proposed $400 billion investment in home and community care for older Americans and people with disabilities could absolutely meet a critical need for those requiring care and for those who are providing it. But where’s the mention of older workers?

A life course approach to longevity

A development life course approach to longevity, spearheaded by a presidential envoy, would recognize that facilitating longer working opportunities can’t just begin in older age. If we raise young people to be lifelong learners, they’ll know how to return for new skills and training at key junctures throughout their lives. Older and younger people should be learning side-by-side, just as they work side-by-side.

When Congress crafts legislation to implement the American Jobs Plan’s investments in job training and other programs, it will be important to include strong oversight and incentives to ensure that employers and employment- support service providers who receive federal dollars prioritize the needs of older workers as much as younger ones.

Similarly, to ensure that older workers have a shot at some of the “good construction jobs” promised in the American Jobs Plan, lawmakers should highlight and prioritize technological innovations to make work in our later years possible. This includes investment in assistive technologies that maintain mobility and take the repetitive strain off of older (and younger) workers in physically demanding jobs.

Also see: Were older workers hurt disproportionately by the COVID recession?

As our nation is “building back better,” it’s time to look at current old-age policy and traditional service delivery models with fresh eyes to determine what should stay, what can go, what needs more funding, what needs to be overhauled and what new programs, private-public partnerships and incentives are needed.

The need for a broad government approach

Preparing for longevity will require a multidisciplinary, broad government approach. A presidential envoy on aging, longevity and retirement security can lead this initiative, conferring with the nation’s aging network and working collaboratively to oversee development of a new policy framework on aging.

This person would be responsible for building consensus around it, choosing priorities and advising on research and infrastructure needs as well as legislative action. The envoy would draw on best practices globally (looking at, for example, what Singapore, Japan, Sweden and the U.K. are doing), host convenings in and out of government and support cross-pollination of ideas from experts in business, the nonprofit sector and academia.

An age and longevity agenda would continue to stand up to prescription drug companies, protect and strengthen Medicare and the Affordable Care Act, preserve and strengthen Social Security and expand and add teeth to age discrimination laws in employment.

Read: How can I make sure that the money I’ve saved will last my whole retirement?

It would also support new programs and initiatives helping older adults maintain their health, well-being and financial wherewithal over a much longer life; invest in biogerontology research; provide incentives to attract more private sector capital and competencies into the longevity space, prioritize redesign of work systems to make work in later years possible; provide incentives to increase the stock of sustainably built affordable housing and support services and provide opportunities for adults of all ages to retool and develop throughout their careers.

It’s time to muster the political will and sustained commitment to meet the challenge of preparing for longevity.

The Older Americans Act has been reauthorized through 2024 and between now and then is enough time to set a new policy framework and approach to aging. A presidential envoy on aging, longevity and retirement security — with the resources, authority, access and backing from the highest echelons of government — can help get the job done.

And now let me add a personal comment:

President Biden and me

I met Joe Biden when he was Vice President at a dinner in his honor at the home of a friend and her husband. As he was leaving, a small crowd gathered; I had a question for him but was too far back to ask. Then he noticed me, a lone 60-something Black woman standing outside the circle that had gathered around him. He motioned for me to come forward. We then talked for about four minutes, mostly about the issue I care deeply about: the financial insecurities of older Americans.

Related: Why won’t anyone hire this 60-year-old?

Not once did his eyes leave my face to scan the room for someone more important to engage — a small thing but rare and revealing in Washington, D.C. where power and optics matter.

On January 20, 2021, Biden, at 78, became the oldest person to take the presidential oath of office. Watching his swearing in, I thought this is a man who knows what it is like to be discounted, underestimated and overlooked because of his age — to be told to step aside to make way for a younger person.

As a 67-year-old Black woman, that’s something I have in common with the president. And I am hardly alone; it’s the experience of millions of older Americans, a generation at risk of being minimized in the 21st century workforce, downsized and outsize into silent shame and poverty.

I hope our president will champion policies and programs for the millions of older adults in their 50s, 60s and beyond who are facing rampant workplace age discrimination and other barriers hindering their participation in the workforce and in life. Appointing a presidential envoy would help.

Elizabeth White is a Next Avenue Influencer in Aging, an aging advocate, a consultant and author of “55, Underemployed and Faking Normal.” Follow her on Twitter @55fakingnormal and on Facebook at 55 & Faking Normal.

This article is reprinted by permission from NextAvenue.org, © 2021 Twin Cities Public Television, Inc. All rights reserved.

More from Next Avenue: