This post was originally published on this site

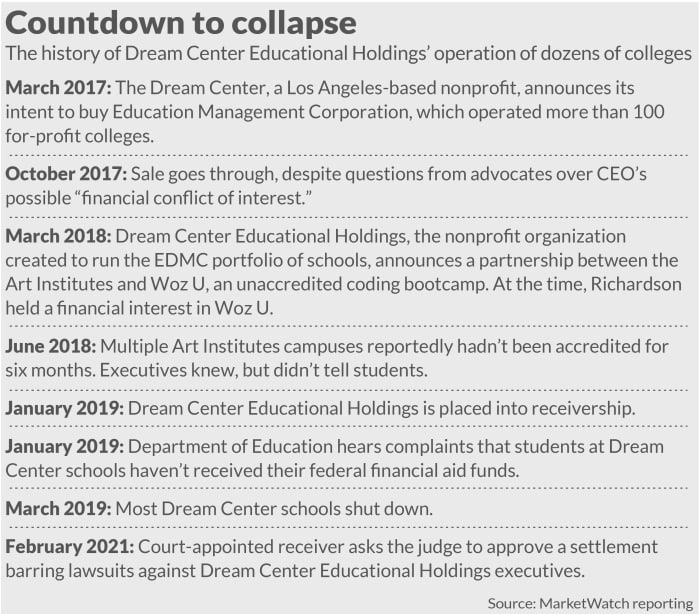

When the Dream Center, a religious nonprofit, agreed to buy dozens of struggling for-profit colleges in 2017, the transaction was hailed as an opportunity for the schools to have a “fresh start.”

The parent company of the schools — which included The Art Institutes and Argosy University — had been investigated for using “boiler room” recruitment tactics to lure students into taking on debt for degrees that didn’t pay off in the labor market.

Just two years later, the schools had closed and the initiative collapsed. Tens of thousands of students had their educations interrupted and were left with an unpalatable set of choices: They could apply to have their federal student loans canceled and start their schooling over, or they could attempt to transfer their credits elsewhere — a daunting task because credits from colleges with for-profit history rarely transfer to public or nonprofit private schools successfully.

The executives who ran the colleges, meanwhile, are expected to graduate from the failed schools with little pomp and circumstance.

Dream Center Educational Holdings availed itself of the opportunity to wind down its operations with few consequences. The organization has been in receivership, a process similar to bankruptcy, since 2019. Mark Dottore, the court-appointed receiver tasked with sifting through the remains of the enterprise, is now asking the judge monitoring the case to shield top executives from any liability over their management of the schools.

The judge, Dan Polster, who is also overseeing sweeping litigation surrounding the opioid crisis, is also being asked to end pending lawsuits that students filed against the executives, alleging they were harmed by the leaders’ and the schools’ conduct. Dottore argued in court documents that a settlement or verdict in one class-action lawsuit filed by students would allow the students to unfairly access the receivership’s assets ahead of other creditors.

If the executives walk away from the Dream Center fallout relatively unscathed, they wouldn’t be the first. Over the past several years, leaders in charge of colleges that have collapsed amid allegations they misled students, investors and taxpayers, have faced little more than fines.

A recent analysis from the National Student Legal Defense Network, which is representing former Dream Center students in litigation, found that the government has failed to collect on more than $1 billion in debt owed to it by higher education institutions. In most cases, the debt is comprised fines for misconduct or student loan discharges when schools collapse or mislead students.

“

‘When students are harmed, executives who hurt them should be held accountable.’

”

“When students are harmed, executives who hurt them should be held accountable,” said Aaron Ament, the president and co-founder of the National Student Legal Defense Network. “We are helping students seek justice and stand up against the Dream Center and its executives. We hope the Department of Education asserts its rights to collect on over $100 million in liabilities it has incurred as a result of the Dream Center debacle.”

In addition to holding executives accountable, advocates for the former students, some of whom are still burdened by the debt they took on to attend these schools, are also urging the Biden administration to ensure that, going forward, leaders of schools at risk of collapse are held personally liable for any financial losses that arise from their conduct — a step they say could decrease incentives for executives to engage in troubling behavior and protect students and taxpayers if the schools do ultimately fail.

The push comes as student loan borrowers and advocacy organizations are watching to see how the Biden administration will approach for-profit college oversight after four years of a Trump-era Department of Education they say was too cozy with the for-profit college and student loan industries. Under President Joe Biden, the Department has already cancelled more than $1.5 billion in student debt from former for-profit college students. But attorneys who represent former for-profit college students say officials must go further.

‘A shameful attempt’ to skirt rules governing for-profit colleges?

Almost as soon as the Dream Center announced it would purchase Education Management Corporation, which owned for-profit college chains including the Art Institutes and Argosy University, consumer and borrower protection organizations began warning the Department of Education about the deal. Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey called EDMC’s decision to sell the schools to a nonprofit, “a shameful attempt” to skirt rules governing for-profit colleges. She noted that the more than 100 EDMC programs showed “outrageous levels of unaffordable student debt.”

A recent report from the Department of Education’s Office of Inspector General, an internal watchdog, found that in reviewing the transaction before the sale went through, the Trump-era Department identified “significant financial risks,” including that the Dream Center had lost the backing of an investor who was supposed to provide at least 50% of the capital for the organization to purchase the schools.

Despite these risks, the Department allowed the transaction to move forward, “deviated” from the Office of Federal Student Aid’s “financial analysis procedures,” and reduced the letter of credit it was requiring the new owners to post, the report found. The Department asks colleges that appear financially risky to post letters of credit often tied to a certain percentage of the financial aid funds an institution receives to mitigate the risk to taxpayers, while still allowing the school to participate in the federal financial aid program.

“

‘It was not a question of if it was going to succeed, but when it was going to collapse.’

”

“It was not a question of if it was going to succeed, but when it was going to collapse,” said Beth Stein, a senior advisor at The Institute for College Access and Success. Between 2010 and 2012, Stein, then-chief investigative counsel for the Senate’s Health Education Labor and Pensions committee, led a landmark Senate investigation into for-profit colleges.

“They’d had a massive settlement,” Stein said, referring to a 2015 deal in which EDMC agreed to pay nearly $100 million to settle claims brought by the Justice Department that the company illegally paid recruiters based on how many students they enrolled.

The settlement and the schools’ poor track record of placing graduates in good jobs, despite the relatively high cost of their degrees, hurt the reputation of EDMC schools, particularly the Art Institutes chain, Stein added. The inspector general report also found that the Department flagged the longtime failing financial health of the EDMC schools as a possible risk associated with the transaction.

‘They would call them synergies, but I would call them conflicts of interest’

But it wasn’t just EDMC’s record that concerned advocates. They also raised questions about the structure of the transaction and the executives involved. As part of the deal, the Dream Center created a nonprofit affiliate organization called Dream Center Education Holdings to run the schools and tapped a group of executives who had been involved in the for-profit college industry for more than a decade to head it.

Brent Richardson served as the organization’s chief executive officer, his brother Chris, the general counsel, and Shelly Murphy, who’d worked with the Richardsons in various companies for years, was the organization’s chief officer of regulatory and government affairs, according to court documents.

The Richardson Family Trust was given the opportunity to play a role in financing the deal, an arrangement that consumer and borrower protection groups said would create a “financial conflict of interest” that could motivate leadership to run the schools for the benefit of financiers instead of students. At the same time Murphy and the Richardsons were embarking on the Dream Center project, Brent Richardson and Murphy were financially and operationally involved with a for-profit technology education company. Court documents allege the roles in both organizations blurred.

“It was clear they were trying to build — they would call them synergies, but I would call them conflicts of interest,” said David Halperin, a Washington, D.C.-based attorney who has written extensively on the Dream Center and for-profit colleges. “There’s just a whole lot of different entities that the same people were involved in over and over again,” Halperin said.

Investors transform a small Christian college

The Richardsons had experience in the business of education. They were part of a group of investors in the mid-2000s that transformed Grand Canyon University from a nonprofit Christian college into an online education juggernaut with a nearly $4 billion market cap — growth fueled in part by aggressive recruiting tactics, a Senate investigation alleged in 2012. Brent Richardson also served as chief executive officer of the school for a period.

Bob Romantic, a spokesman for Grand Canyon, wrote in an email that the school “grew rapidly” after taking on investors “as a way to raise capital and grow the university as a for-profit institution,” adding that the growth has been consistent over the past 12 years, including during the pandemic.

“That growth is a reflection of our ability to offer private Christian education that is affordable to all socioeconomic classes of Americans,” Romantic wrote, noting that the school hasn’t raised tuition on its in-person campus in 13 years and citing the school’s loan default rate of 5.6% (The share of borrowers nationally who defaulted on their loans within three years of entering repayment was 9.7%).

The institution, he said, has grown because of the relative value it offers at a time when the cost of higher education has been growing 3½ times as fast as the cost of living.

Richardson’s involvement with the school proved lucrative. Over the years, he’s earned millions selling Grand Canyon stock, including on election day 2016, when he sold 55,000 shares worth $2.6 million.

A fizzled partnership with Woz U

Not long after the Dream Center took over the EDMC schools, challenges with the executives’ management of the portfolio became apparent. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported in June 2018 that multiple Art Institute’s campuses hadn’t been accredited for roughly six months. Accreditation is a seal of approval required for schools to receive federal financial aid and lends schools and credentials legitimacy in the labor market.

Though executives knew the campuses weren’t accredited, they didn’t tell the students, court documents allege. Students enrolled, borrowed and paid to attend the schools, unaware of the change in status that could put the schools’ future and their careers in jeopardy.

During the same period, Brent Richardson pushed the Art Institutes to offer a software development program through a partnership with Woz U, a for-profit, non-accredited technology education company, according to a report from the court-appointed administrator overseeing the settlement between Dream Center Educational Holdings and the Department of Justice (DCEH inherited the settlement from EDMC). At the time, according to the report, Brent Richardson held a financial interest in Woz U and Murphy was a spokesperson for the company, which describes itself as created by Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak.

Under the arrangement, Dream Center Educational Holdings was set to pay Woz U a $20,000 start up fee, another $10,000 per campus where the Woz U program opened, and 30% of the funds received for tuition payments and various fees, according to the report.

When employees raised questions about the structure of the relationship between Art Institutes and Woz U and how that might impact Dream Center’s compliance and accreditation requirements, Richardson responded, “Understand this. I run DCEDH. I run Woz U. You don’t question this,” according to the documents.

The partnership ultimately fizzled, but it sparked concern from the court-appointed administrator overseeing the settlement between Dream Center and the Department of Justice about whether marketing materials for the program misled students about the relationship between the Art Institutes and Woz U in the initial rollout of the partnership.

‘Worse off than they expected’

Another “set of issues,” related to the partnership, the administrator wrote, “dealt with whether, given the involvement of DCEH CEO Brent Richardson and others in Woz U, DCEH management was using their non-profit educational institution to provide themselves financial benefits through other vehicles.”

Leo Beus, an attorney representing Brent Richardson, declined to comment on any of the details in this story. “Whatever story you write, I don’t think it will be accurate” if it implies his client did anything wrong, Beus said.

The court-appointed administrator overseeing the settlement between the Department of Justice and EDMC, which Dream Center inherited, noted in a report that included materials and interviews in the year leading up to October 2018, that Dream Center Educational Holdings leadership “is clearly driven to save what they believe to be a business at serious risk of failure.”

“One they believe to be worse off than they expected or were led to understand at the acquisition — and have found limited capital available to invest in its long-term compliance future,” he wrote.

An attorney representing Brent and Chris Richardson in a lawsuit filed by former Art Institute students alleging they and Murphy knew about the schools’ accreditation issues and intentionally misrepresented that to students, didn’t respond to multiple messages seeking comment. Murphy also didn’t respond to multiple emails seeking comment. When a reporter called a phone number listed in court documents as belonging to Murphy, she was told she had the wrong number.

Students’ financial aid stipends went missing

Roughly two years after purchasing them, Dream Center Education Holdings sold or closed the bulk of the EDMC schools despite lobbying the Trump-era Department of Education to fix the accreditation issue and keep federal financial funds — taxpayer dollars that are crucial for most colleges to operate — flowing to the schools.

Amid the collapse, the organization entered receivership, a process that, unlike bankruptcy, allowed Dream Center Educational Holdings to continue to access federal financial aid. Still, it wasn’t enough to staunch the harm to students. In the same month the court-appointed receiver took over, students at some Dream Center schools noticed that their financial aid stipends — the money students receive in excess of tuition to pay for living expenses — were missing.

Marina Awed was in her last semester of law school when she intervened in the Dream Center Educational Holdings receivership.

“I was really scared that the school was going to shut down and that I was going to have to start law school all over,” Marina Awed said of that period. Awed was in her final semester at Western State College of Law, a law school in the Dream Center portfolio, when her financial aid funds went missing.

Once Awed realized she and her fellow students’ fates were tied up with the Dream Center’s corporate unwinding, she intervened in the receivership, speaking to the judge about how the situation was impacting her life and career.

More than two years later, Awed, who was able to finish law school and is now an attorney at her own firm, the Awed Law Group, is still waiting for answers about where that financial aid stipend went. The Department of Education sent the funds to Dream Center Educational Holdings to distribute to students, according to a 2019 letter from the agency, but it’s still unclear where the money went.

The inspector general report found that in February 2019, the receiver sent the Department a list showing about $16 million in unpaid student stipends and disbursement request. The watchdog found that neither the Dream Center nor the schools themselves drew down the funds for the students on the list and the students never received the payments. An attorney for Dottore wrote in an email that records related to the stipends were turned over to the government for investigation.

“Maybe to them millions of dollars is not that big of a deal,” Awed said, speculating about the Department of Education’s motive in not doing more to seek out the missing funds.

“What occurred with the Dream Center during the previous administration underscores the importance of stronger policies to review and approve changes in ownership among colleges and universities,” a department spokesperson wrote in response to the inspector general’s report. “These students simply deserved better. Our administration is committed to strengthening the department’s policies to protect against situations such as this from occurring again — including through upcoming regulatory action.”

The agency also plans to review policies surrounding letters of credit, “to ensure that we have sufficient financial protections in place for taxpayers,” the spokesperson wrote.

A contentious settlement that could protect execs

Now, Dottore, the receiver, is pursuing a settlement that would protect Dream Center Educational Holdings’ directors and officers, including the Richardsons and Murphy, from lawsuits arising out of their conduct while they ran the Dream Center schools.

Under the terms of the deal, the executives would agree to direct one of the insurance policies taken out by Dream Center Educational Holdings that protected them from liability over conduct arising out of their roles at the organization to pay $8.5 million to the receivership estate. In exchange, Dottore would agree not to pursue legal claims against the executives under that policy (he could still pursue additional claims covered by other tiers of insurance held by DCEH).

The agreement is contingent on barring all past, present and future lawsuits over the same conduct, Dottore stated through a brief filed by his attorney. If the insurance policies pay out $8.5 million as part of the deal, the executives’ coverage would be exhausted. In the absence of the bar order, they face the risk of litigation without insurance coverage. “That is an untenable result” for the executives, the February court documents read.

If the court approves settlement, students and other creditors could file claims asking to benefit from those funds. Still, at least one group of students — former Art Institute students who filed a class-action lawsuit against the school, DCEH, the Richardsons and Murphy — are unlikely to receive anything from the receivership estate, according to court documents filed on Dottore’s behalf.

Students may not be compensated

They “are not entitled to a claim in this receivership,” the July documents argue, because they have already been compensated for any potential claims by the discharge of their federal student loans. In addition, the brief states that the government or taxpayers’ claims against the receivership include the money paid to the students as part of the loan discharge.

February court documents filed on behalf of Dottore also accused the students, who are represented by National Student Legal Defense Network, of pursuing their claims in another forum “and snatching payment from the very assets that should have paid the Receivership’s stayed creditors.”

The students’ attorneys pushed back against the notion that they were already compensated for the harm they allegedly experienced through loan discharges, writing in August court documents that loan cancellations don’t include refunds for money spent out of pocket or through private loans to cover the students’ education.

In addition, the attorneys wrote, the students aren’t trying to recover loan cancellations twice through their lawsuit. Instead, they’re seeking other college expenses they haven’t been compensated for, as well as damages.

In affidavits, the four named plaintiffs in the lawsuit described the harm they experienced as a result of the executives’ alleged conduct in their own words. They described receiving transcript addendums from the Illinois Institute of Art saying that courses or degrees completed since January 20, 2018 were not accredited.

They are each seeking damages. The highest amount of individual damages among the named plaintiffs is $108,177, which would cover the entire cost of attendance minus grants, federal student loan discharges and refunds on debt owed to the school. The judge overseeing the students’ lawsuit in Illinois recently denied the motions to dismiss the case filed by the Richardsons and Murphy. But if the Ohio court approves the bar order, the future of the suit could be in jeopardy.

The former students wrote to the judge that they and other potential members of the class “should be permitted to pursue our claims for damages against the Dream Center Foundation, Brent Richardson, Chris Richardson, and Shelly Murphy.”