This post was originally published on this site

The stock market is not a bad place to be if high U.S. inflation turns out to be more than transitory. It’s also not a bad place to be if inflation’s recent spike turns out to be merely temporary.

This relationship that stocks have to inflation is comforting, because the current inflation debate remains as unresolved as ever. Even though the most recent U.S. inflation data showed the Consumer Price Index in July to have retreated slightly from June, its 12-month rate of change still stands at a 20-year high.

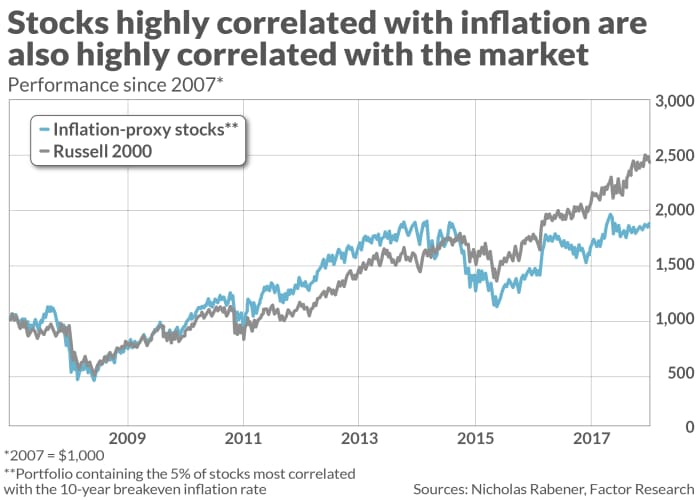

Consider the performance of a hypothetical portfolio constructed by Nicholas Rabener, founder & CEO of FactorResearch in London. The portfolio contained the 5% of stocks that, at any given time, had the highest trailing five-year correlation with the 10-year breakeven U.S. inflation rate. That rate equals the difference in yields between the 10-year U.S. Treasury

TMUBMUSD10Y,

and 10-year TIPS; it represents the bond market’s bet of what inflation will be over the coming decade.

The chart below shows that this hypothetical portfolio was highly correlated with the Russell 2000 index

RUT,

a benchmark for the small- and midcap sectors of the U.S. stock market. Meaning that when there is an unexpected uptick in inflation, the most inflation-sensitive stocks don’t on average do any better or worse than a broad index fund.

This is good news because it means you don’t have to go out of your way to find the handful of stocks most likely to perform best if inflation climbs even higher. A Russell 2000 index fund, such as the iShares Russell 2000 ETF

IWM,

should do just as well, assuming the future is like the past.

What if higher inflation is transitory? The lesson of the chart is that a Russell 2000 index should also perform fine.

To be sure, Rabener emphasized in an email, his analysis focused only on the past two decades, for which data exists for the breakeven inflation rate. Upon focusing instead on changes in the CPI back to the late 1940s, he did find that certain sectors — notably energy — outperformed the market when inflation was high. Nevertheless, he added, this knowledge has “only limited practical value as investors are not particularly skilled at forecasting inflation.”

Value and growth when inflation is high

I reached similar conclusions when analyzing growth- and value stocks during high- and low-inflation environments. That’s surprising, since the widespread narrative on Wall Street is that value stocks are the place to be when inflation is heating up.

This narrative is mistaken, as I reported in a June 2021 column, because there is an inconsistent correlation between value stocks’ relative performance and the CPI’s trailing 12-month change. Yes, value’s relative strength vis-à-vis growth has been positively correlated with inflation at times; this past year has been one such occasion.

Yet there have been other times when just the opposite has been the case. Perhaps the most spectacular example of this came in the wake of the internet bubble’s bursting, when inflation expectations fell dramatically and value beat growth by a huge amount. In fact, value beat growth in the early 2000s by more than in any other several-year period in the past century.

The bottom line? We have yet more evidence of the stock market’s famous efficiency. It does a remarkable job reflecting all information that investors collectively have at any given time. By the time you or I read the inflation headlines, that reality has long since been reflected in stock prices. We gain no advantage over the market by shifting into or out of value stocks after reading those headlines.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: One look at junk bonds tells you that stock investors now are too bullish

Plus: The housing market is so hot, a burnt-out Bay Area home is drawing cash bids above $850,000