This post was originally published on this site

A documented rise in drug-overdose deaths during the pandemic has disproportionately impacted Black and Native Americans, according to a new analysis of government data spanning 2018 to the first several months of COVID-19.

While death rates for drug overdoses grew for all racial and ethnic groups from 2018 to 2020, Black and American Indian and Alaska Native people experienced the biggest increases, according to the report by Kaiser Family Foundation, a healthcare think tank.

In the period between January and September 2020, American Indian and Alaska Native people saw the highest drug-overdose death rates (29.8 per 100,000). Black Americans had the next highest rate (27.3 per 100,000), followed by white Americans (23.6 per 100,000).

While white people still make up the biggest share of drug-overdose deaths in the U.S., Black and Hispanic people have constituted an increasing percentage of these deaths over the past few years, KFF noted, adding that some recent data have shown relatively large shares of people of color reporting substance use.

“These increases in substance use problems come at a time when many people of color have faced a number of negative effects of the pandemic, including increased mental distress and job loss and infection and deaths due to COVID-19,” the KFF authors wrote.

Of course, substance-use disorders were widespread before COVID-19 struck, the report said — but many people who needed treatment weren’t getting it, especially people of color. People’s access to and use of substance-use treatment and services, at least during the pandemic’s early stage, may also have taken a hit, in part because of state and local budget pressures and limitations on how services are delivered.

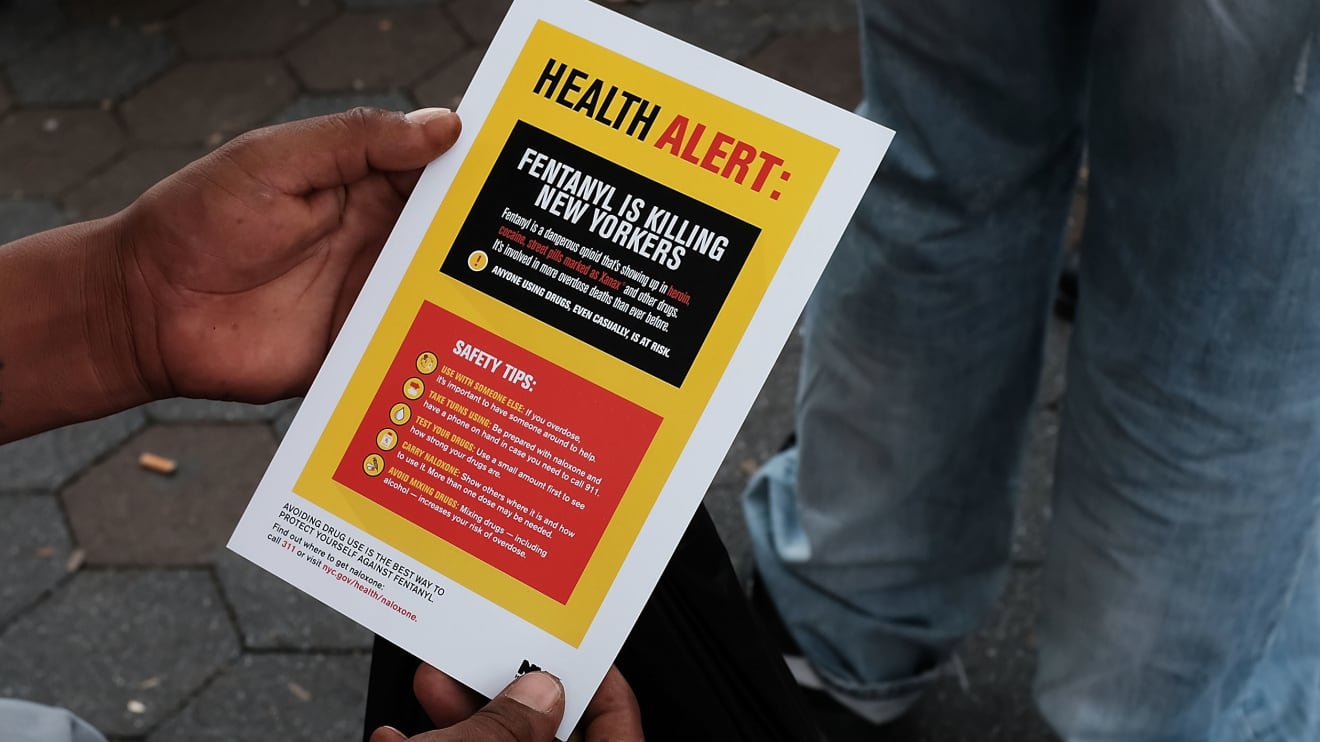

U.S. drug-overdose deaths grew by almost 30% last year to more than 93,000, according to preliminary data published in July by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Experts attributed the record-high number of deaths to the potent synthetic opioid fentanyl, as well as heightened unemployment, social isolation and mental-health impacts brought on by the pandemic.

“

‘COVID-19 has exacerbated preexisting stressors, social isolation, and economic deprivation disproportionately in Black communities, possibly contributing to increased substance use.’

”

During a virtual discussion at the Rx Drug Abuse and Heroin Summit in April, National Institute on Drug Abuse director Nora Volkow described “a perfect storm” contributing to overdose deaths involving not just opioids but also stimulant drugs.

“We have people stressed to their limits by decreases in the economy, the loss of jobs, the death of loved ones,” Volkow said. “On the other hand, we see dealers taking the opportunity to bring in drugs such as synthetic opioids and synthetic stimulants and distribute them to a much wider extent than previously seen.”

Trends contributing to overdose deaths have “shifted,” Volkow added, from mortality in the early stages of the opioid crisis being largely associated with white Americans in rural or semi-suburban parts of the country.

“The highest increase in mortality from opioids, predominantly driven by fentanyl, is now among Black Americans. They’ve had very, very high rates of mortality during the COVID pandemic,” she said. “And when you look at mortality from methamphetamine, it’s chilling to realize that the risk of dying from methamphetamine overdose is 12-fold higher among American Indians and Alaskan Natives than other groups.”

Previous research has uncovered racial disparities in drug-overdose deaths during the pandemic: An analysis of overdose data in Philadelphia through June 2020, for example, found that overdose deaths among Black Philadelphians increased more than 50% from the same period a year earlier. Meanwhile, white residents’ overdose deaths fell, according to the research letter published in the journal JAMA Network Open.

“COVID-19 has exacerbated preexisting stressors, social isolation, and economic deprivation disproportionately in Black communities, possibly contributing to increased substance use,” the study authors wrote. “The preexisting racial disparities in accessing substance use treatment may also be heightened by COVID-19–related shifts in treatment availability.”

Addiction experts who spoke to NPR earlier this year also pointed to policies stemming from the country’s “war on drugs” — arguing they had created a two-tiered system by which wealthy and white Americans experiencing addiction can access needed treatment and healthcare, while poor people and people of color often encounter punitive consequences and face barriers to accessing care.

Some recent federal policy moves — like $4 billion in the American Rescue Plan Act for mental health and substance-use programs, looser restrictions on how substance-use care is delivered, and Biden administration efforts to increase healthcare access — could help people experiencing substance-use issues, the KFF report said.

But “a number of challenges remain,” the nonprofit added, including higher-than-usual unemployment and mental-health concerns, which are associated with substance use.