This post was originally published on this site

Millions of Americans now receiving pandemic aid will see their benefits end in September.

There’s no shortage of politicians, corporate executives and economists who say this is good, claiming the no-strings-attached cash has acted as a disincentive to work. The number of job openings nationwide, which swelled to a record 10.1 million at the end of June, would appear to support this point.

But is this conventional wisdom wrong? Based on preliminary data from more than two dozen states, which have already cut off an extra $300 in weekly unemployment benefits to some 3.5 million Americans, it may be.

Dr. Arindrajit Dube, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, has looked at what has happened in those states. He notes that half of U.S. states have ended all or most of the pandemic unemployment insurance (UI) programs, the vast majority in June. All have stopped the $300 weekly payments, called Pandemic Unemployment Compensation, or PUC. Twenty-one of 25 have ended Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation, or PEUC, which extend benefits beyond the 26 weeks that most states offer.

An unexpected finding

So what happened next?

Since millions of jobs aren’t being filled, wouldn’t those getting cut off quickly find work? Dube’s research points to a different, albeit preliminary, judgment. Looking at a key data point — weekly employment to population ratio (EPOP) relative to the expiration of benefits — he writes that “between early June and early July, the EPOP rates in the states seeing large drops in (unemployment payments) saw no uptick in employment.”

In fact, the ratio declined by 1.4 percentage points over the same period, while rising 0.2 percentage point in states that did not end pandemic payments.

To sum up: Benefits have been cut off, but Dube says this “doesn’t seem to have translated into most of these individuals having jobs in the first 2-3 weeks following expiration.”

To be fair, it’s early, as the professor writes, and that “more data is needed to paint a fuller picture.” We’ll get more data next week, when the Labor Department issues its state employment and unemployment for July.

Different forces at work

What’s going on here?

“Early indications are that (unemployment) benefits have had some effect on job search,” says Julia Pollak, chief economist at Santa Monica, California-based Ziprecruiter, “but the effect is likely rather small because there are other things that are keeping people out of the labor force.”

She cites the obvious reason: The pandemic, which is resurgent in much of the country, and child care, which has caused droves of workers — largely women — to stop working. Data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas puts this number at 1.3 million.

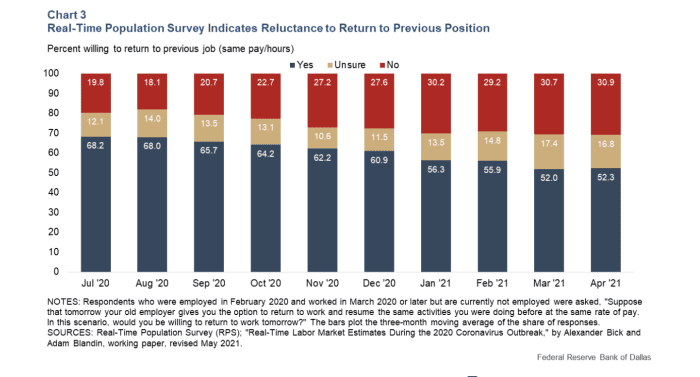

There is other data. The Dallas Fed says 31% of workers are reluctant, for whatever reason, to return to their previous job. It’s a data point that has increased slowly but steadily for more than a year.

Beyond this, there are actually some pretty good reasons for people to take their time going back to work. Lots of Americans, pandemic notwithstanding, are feeling flush. In case you’ve forgotten, the pandemic occurred at the end of a long stock market expansion, and after the short-lived bear market of February-March 2020, prices fully recovered and then some. Meanwhile, housing prices have surged nationwide, allowing millions to refinance at lower rates and take out cash. Savings have also surged.

“The country went on an unprecedented saving spree,” says the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

On top of this, there is all the cash — trillions — dropped on Americans by the Trump and Biden administrations.

The unemployed are taking their time

A rising tide doesn’t lift all boats, but it has lifted enough, Pollak says, to give many Americans the sense that they don’t have to jump at the first job offer that comes their way.

“We ask active job seekers: Do you feel financial pressure when looking for a job? And only about a third feel compelled to take the first offer they get,” she says. “People have more time. That’s a challenge for employers.”

Thus, jobs aren’t being filed because folks are getting a measly $300 a week from the government. They’re not being filled because people aren’t financially compelled to go back to work, particularly if it involves commuting.

There’s a broader observation to be made about working for the sake of working, of striving and achieving and proving yourself in the marketplace, regardless of the financial position you’re in. But that’s a discussion for another day.

And I don’t want to sugarcoat this. There is no question that millions of Americans are struggling, and for whom $300 a week is a big deal. But there’s also plenty of data to suggest that many others are riding out the pandemic in good shape.

There’s no one-size-fits-all policy to accommodate everyone. If times are flush for millions, then surely we can find a way to continue helping those who aren’t so fortunate.