This post was originally published on this site

Americans have been spoiled for decades by an environment of low inflation. Now that inflation is back — for however long that lasts — we need to change the way we think about our incomes, investments, debt and spending.

Inflation changes everything, and sometimes in surprising ways. If we don’t factor inflation into our calculations, we’re going to get fooled time and time again by what economists call “the money illusion.” The danger is that we might believe we’re doing better financially than we really are because we’re paying attention to nominal figures instead of what our money can buy.

Breaking news: U.S. inflation shows signs of moderating in July

The money illusion

Investopedia explains the money illusion this way: “People have a tendency to view their wealth and income in nominal dollar terms, rather than in real terms.”

“In other words,” says Wikipedia, “the face value (nominal value) of money is mistaken for its purchasing power (real value) at a previous point in time.”

Amid low inflation, such as the period from roughly 1990 to 2020, the purchasing power of a dollar didn’t change that much from year to year, so people could sort of get away with ignoring how inflation was slowly eroding their income and wealth. But that denial is no longer tenable.

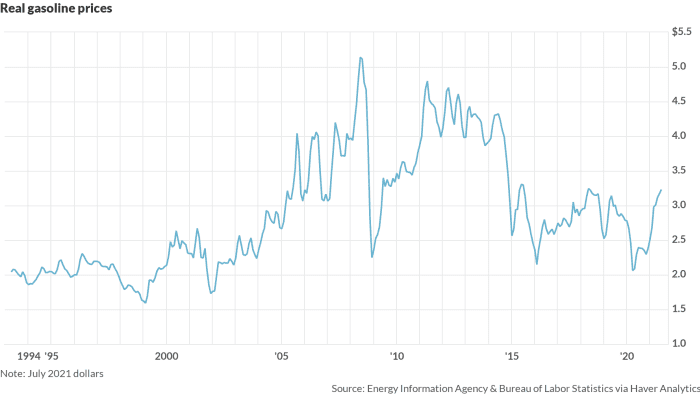

We see the money illusion everywhere, and it’s going to be a problem as long as inflation remains high. For instance, we often hear of people bragging that their home’s value has doubled in 10 years. We hear politicians griping that gas prices are the highest they’ve been since 2014.

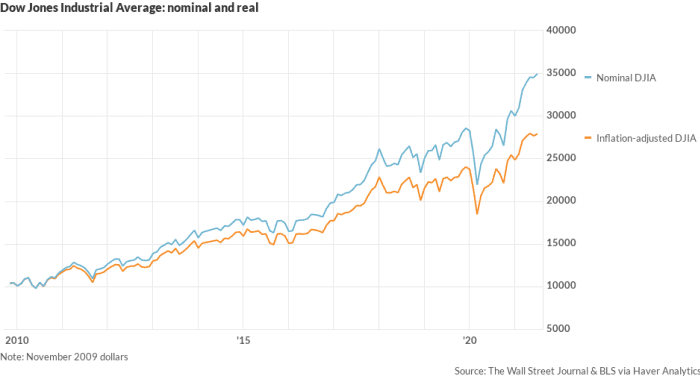

And the market cheerleaders tell us that the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

closed at a record level on Tuesday.

We aren’t as wealthy as we think.

Those people are suffering from the money illusion, because they are ignoring the effects of inflation on the purchasing power of a dollar over time. In real terms, their home’s value is up 55%, not 100%. In real terms, gas prices are down 24% versus the 2014 peak. And, in real terms, the Dow hit a record on May 10, not Aug. 10. (Throughout this column, I am using the consumer price index to adjust nominal values.)

Gasoline is about $1 cheaper than it was at the peak in 2014.

Those people are pretending that the nominal price of houses, equity shares or gallons of gas today is directly comparable to what it was months or years ago. It’s like your smug granddad lecturing you about how a candy bar “ought” to cost a nickel, just as it did back in the day.

Everyone knows a nickel isn’t worth what it used to be and we should start acting like we know it.

Wages are really falling

Sometimes the money illusion clouds how we see the broader economy. If we look at the 4% increase over the past year in nominal hourly earnings, we’d think workers were doing OK and that maybe higher wages are pushing up selling prices, which would be a worrisome sign that the current spate of inflation is going to become permanent.

But real wages aren’t even keeping up with inflation. Real earnings are down 1.2% in the past year and have fallen at a 3.3% annual pace so far this year. Inflation isn’t a wage-push story.

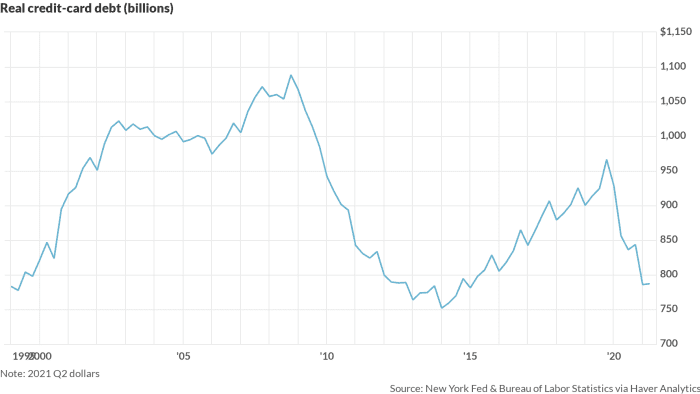

Another example: There’s been a lot of news recently about how Americans are bingeing on credit this year. But the economists and journalists responsible for this story line are suffering from the money illusion.

Yes, in nominal terms, household debt rose in the first half of the year. But in real terms, debt was unchanged. What’s more, real credit-card debt has dropped by $179 billion since the end of 2019; it’s as low as it was in 1999.

Credit-card debt is not exploding, as some are telling us.

Americans are still deleveraging, just as we have been for more than a decade. It’s only the large run-up in inflation this year that makes it seem as if debt levels are rising. We’re going to pay back this debt with inflated dollars, so it makes sense to analyze it in real terms.

We shouldn’t let our brains give us the wrong idea about what’s really going on.

The money illusion makes it seem as if our incomes, our assets, our debts and our spending are all bigger than they really are. What matters most is what our money can buy.

Rex Nutting has been covering the economy for MarketWatch for more than two decades.