This post was originally published on this site

There’s a limit to how much happiness money can buy.

That’s one of the more provocative lessons I draw from a recent survey of retirees conducted by the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI). Conducted last fall, the EBRI surveyed 2,000 retirees between the ages of 62 and 75 with less than $1 million in retirement assets. One of the numerous questions on the survey asked retirees to rate their level of satisfaction with retirement life.

The ability to correlate their answers with retirement assets traces to how the EBRI sliced and diced their sample. Based on income, wealth and spending factors, retirees were placed into five categories or profiles.

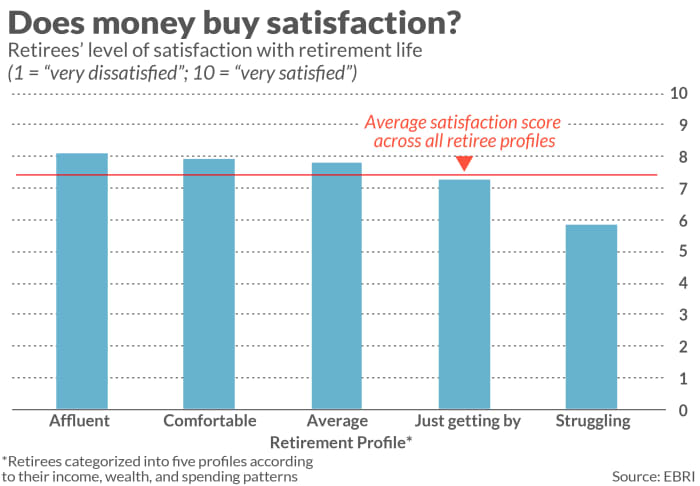

The accompanying chart plots these five profiles’ average satisfaction scores. Notice that, but for one profile, the scores all fall within a fairly close range.

The one outlier is the so-called “Struggling” profile, with an average satisfaction score of 5.75, with 1 indicating extremely dissatisfied and 10 indicating extreme satisfaction. And it’s hardly a surprise that retirees in this group had lower satisfaction levels than the other four.

That’s because, according to EBRI, the retirees in this profile “had low levels of financial assets (less than or equal to $99,000) and income (less than $40,000 annually)… more likely than any other group to rent rather than own their homes; … most likely to have unmanageable debt, such as credit card and medical debt… [and] rely on Social Security to provide the bulk of their retirement income.”

At the other end of the spectrum, retirees in the EBRI’s “Affluent” profile typically had high levels of financial assets ($320,000 or more) and annual income of $100,000 or more. Furthermore, “they were mostly mortgage-free homeowners, with no debt… [and] rarely reported having credit card and auto loan debt.” So it’s entirely to be expected that retirees in this category would report higher satisfaction levels than retirees in the “Struggling” profile.

What is surprising, however, is the average satisfaction scores in the three profiles in between these two extremes. Notice that they are quite close to that of the “Affluent” profile. Though I don’t have access to the underlying data, my hunch is that the differences in the scores for these upper four profiles (all those besides the “Struggling” category) aren’t statistically significant.

The conclusion I draw: Once we jump over some initial financial hurdle in preparing for retirement, there’s relatively little correlation between more wealth and greater happiness. Furthermore, that initial hurdle is fairly low.

The investment implications

Perhaps the most important investment implication I draw from this is that it’s better to avoid the worst-case scenario than it is to “shoot the moon” and bet everything on attaining the best-case scenario. Once you have your basic financial needs met, additional wealth has quickly diminishing returns in terms of your retirement satisfaction. So it makes little sense to incur inordinate risks in pursuit of those diminished returns.

One portfolio move you might make in response to this investment implication is to annuitize part of your retirement portfolio. By doing that you can lock in a guaranteed monthly payout that will last as long as you (or a spouse) live. Your goal might be to annuitize enough of your portfolio so that you jump over the low hurdle identified in the EBRI survey—thereby avoiding ending up in the “Struggling” profile of retirees.

To illustrate, consider the stream of annuity payments you could lock in if you purchased a $100,000 annuity as a single male, aged 65. According to ImmediateAnnuities.com, at current rates you could secure a guaranteed monthly income of $501 per month until your death. That would be above and beyond any Social Security or pension payments you are already entitled to.

Whether or not an annuity is a good idea depends on a host of factors, such as whether you are likely to outlive your actuarial life expectancy. You most definitely should consult a qualified financial planner before considering an annuity, since the devil is in the details.

In any case, note that it’s unlikely you’ll want to annuitize your entire retirement portfolio. The optimal amount depends on any of a number of assumptions—such as your age, your marital status, your portfolio size, your life expectancy, the markets’ returns, and so forth. Several years ago, David Blanchett, head of retirement research at Morningstar, analyzed more than 78,000 possible scenarios, each one of which represents a different set of assumptions. The average optimal annuity allocation across all those scenarios was 31%.

The bottom line? Only to a limited extent can money buy you retirement satisfaction. Plan accordingly.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com