This post was originally published on this site

This article is reprinted by permission from NextAvenue.org.

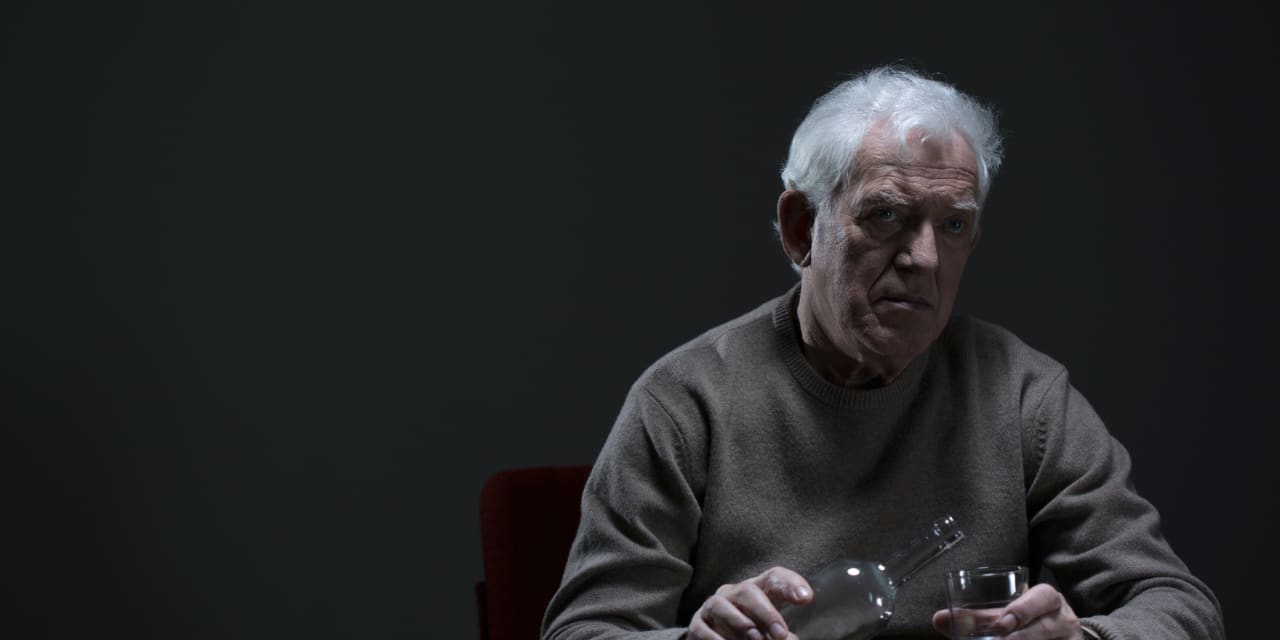

Probably most of us at some time during later life are way more focused on what’s in the rear view than on what’s ahead. This is not necessarily a problem, but if it prevents us from dealing with — or even really seeing — what’s on the horizon, it can be a sign of what has come to be known as the late-life crisis.

The late-life crisis, like its more famous younger sibling, the midlife crisis, really is a thing. Recent research has found that as many as one in three people over 60 will experience it in some form.

The late-life crisis is characterized by dissatisfaction; a loss of identity; an expectations gap and the feeling that life has peaked, so it’s all downhill from here.

The late-life crisis vs. the midlife crisis

While the midlife crisis is typically about the loss of opportunities, the late-life crisis is more about the loss of relevance. Stereotypically, during the midlife crisis, you dye your hair and buy a sports car; during the late-life crisis, it feels pointless to even get out of your bathrobe.

Also, unlike the midlife crisis, which popular culture and the punchlines of late-night comedians tell us is mostly a guy thing, the late-life crisis is not gender-specific. Women and men seem equally likely to experience it.

The particulars of the crisis can be hard to pin down. Is it a time of massive change and reprioritization? A mysterious chasm between the past and the future? Or just a normal sad and panicky feeling of anxiety in response to the challenges of aging?

In a word, yes to all of those.

The late-life crisis can be triggered by a crucible event. The death of a loved one, an illness, money problems or even something as simple as no longer being able to complete that favorite hike or bend into that particular yoga pose can set it off. Or, it can simply be the mind-draining drudgery of more of the same. One day we’re an “active ager” embracing the experience of later life; the next we’re feeling invisible and irrelevant.

Of course, outward changes acknowledged, the real crisis is taking place on the inside. Our response to the inevitable changes brought on by age is what determines whether we’ll experience crisis or have the mind-set to reimagine our future.

Will we get stuck in the past and overwhelmed by morbid thoughts about the end of life? Or will we draw upon past lessons and learning and focus instead on how to make the most of the rest of our life?

Learn more: Depression isn’t a ‘normal’ part of aging — how to treat and prevent it

Your life before the crisis point

Part of the answer has to do with how we’ve lived up until the crisis point.

If we generally feel fulfilled by a life well spent, we’re apt to have the mind-set to glance back in the rearview mirror with satisfaction and to look forward through the windshield with hope. But if we’re in the midst of a long arc of dissatisfaction that has been simmering for some time, we’re more apt to feel despair when faced with limited years and what we take to be limited possibilities ahead.

Most of us go through periods in our lives when we feel like something’s missing, when it seems like we’re off course or lack direction. But the late-life crisis is different. In the late-life crisis, we feel the clock ticking.

One thing is certain, however: the degree to which we are able to admit being in the late-life crisis determines the degree to which we’ll be able to move through it.

Questions to ask yourself

Asking ourselves a series of questions, like those that follow, can help us to see whether we’re experiencing a crisis:

Do you often find yourself looking in the mirror and thinking, “Who is this person?”

Do you feel reluctant to tell people your age?

Do you obsess about your appearance, trying to “anti-age,” to look younger?

Do you often compare yourself with others your age (and worry that you’re not measuring up)?

Do you often find yourself thinking about your mortality?

Do you avoid discussing with your loved ones what you would like for them after you’re gone?

Do you often question the value of your religious or spiritual beliefs?

Do you often feel down or empty for long periods?

Do you often feel detached from activities that once gave you pleasure?

Do you feel bored or stuck in your personal relationships?

You might relate to a few of these behaviors, thoughts and feelings. But if you answered a definite “yes” to more of the questions than you answered “no,” it’s possible that you are in (or entering into) a late-life crisis.

So, what can you do if you know that you’re in (or on the cusp of) a late-life crisis? How can you successfully move forward?

It is useful to frame the crisis in a new way.

Also read: Am I lonesome? ‘I’m fine. I’m fine.’ How single men can prepare to age alone

How to frame a late-life crisis

The late-life crisis is an opportunity for us to reframe what it means to get old — to change our mind-set from danger to opportunity, from living a default life to living a good life. This means choosing how to see a new image in the mirror.

Instead of looking back and lamenting our losses and what we never did, we can gaze in the rearview mirror and see the lessons we can learn from it. Reflection on the past can be an opportunity for growth — a chance to draw upon our past experiences in order to apply that insight to the future.

Also on MarketWatch: Love and money: How your relationship with your spouse and your finances are connected

Instead of living life in the rearview mirror, focused on “shoulds” (I should have worked harder, loved better, learned more, earned more), we can live for the windshield and practice more of the “coulds” (I could work harder, love better, learn more, and so on) from here on out.

The late-life crisis is an opportunity for us to acknowledge that we need to have real conversations with family, friends and others. Key to avoiding or managing a late-life crisis is to not go it alone; isolation is fatal.

We should also aim not to be a person of success, but rather a person of value. Being a person of value requires transcending self-absorption and taking a stand on the highest and holiest vision of life. It means doing more of what our deepest self desires. It means growing whole through crises.

Research has consistently shown that people who persevere through war, natural disasters, economic strife, divorce, illness and loss of loved ones can come out on the other side stronger and more resilient.

Purpose is even more essential for surviving and thriving in bad times.

Purpose and practice

Purpose is a verb; it is a path and a practice. Any number of practices can help a person avoid or handle a late-life crisis, just so long as the person commits consistently to those practices.

For instance, the practice of journaling can help us better understand ourselves, but only if we journal on a regular basis.

The good news is that later life can be the perfect time to commit to such practices, since there are likely to be fewer obstacles in the way of our doing so. We’re apt to no longer have the excuses, like a busy work schedule or a long daily commute, that enabled us to avoid committing ourselves earlier in our lives.

Sometimes, as we get older, we’re inclined to think that it’s too late to grow older — to get started doing something new — and besides, why not just relax and enjoy life as we know it?

Point taken.

On the other hand, our recognition that the time we have left is limited can be a spur to action. Knowing that we have limited years remaining to grow in some aspect of our life may be the inspiration to finally do so.

This article is an excerpt from “Who Do You Want to Be When You Grow Old? The Path of Purposeful Aging,” by Richard J. Leider and David A. Shapiro, published by Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Richard J. Leider is the founder and of Inventure: The Purpose Company, whose mission is to help people unlock the power of purpose. Widely viewed as a pioneer of the global purpose movement, Leider has written or co-written 11 books including three bestsellers which have sold over one million copies. His latest book is “Who Do You Want to Be When You Grow Old?”

David A. Shapiro is a philosopher, educator and writer whose work consistently explores matters of meaning, purpose and equity in the lives of young people and adults. He is a tenured philosophy professor at Cascadia College, a community college in the Seattle area. He is co-author of “Who Do You Want to Be When You Grow Old?”

This article is reprinted by permission from NextAvenue.org, © 2021 Twin Cities Public Television, Inc. All rights reserved.

More from Next Avenue: