This post was originally published on this site

Much has been said about the decline of the value premium in stock markets. For at least a decade now, value investors have had a terrible time and the resurgence of value stocks this year has been pretty mild in the United States, though much stronger in the U.K., for example.

But the question if value is dead is one that still haunts us and when it comes to U.S. stock markets

SPX,

(but not the U.K. or Europe), so does the question if small-cap stocks really earn a premium.

In this respect, I like the approach by Simon Smith and Allan Timmermann who looked at 23,000 U.S. stocks from 1950 to 2018 and calculated not just the risk premium for value stocks, small-cap stocks and other factors over time, but also tried to identify breakpoints in the performance of these stocks.

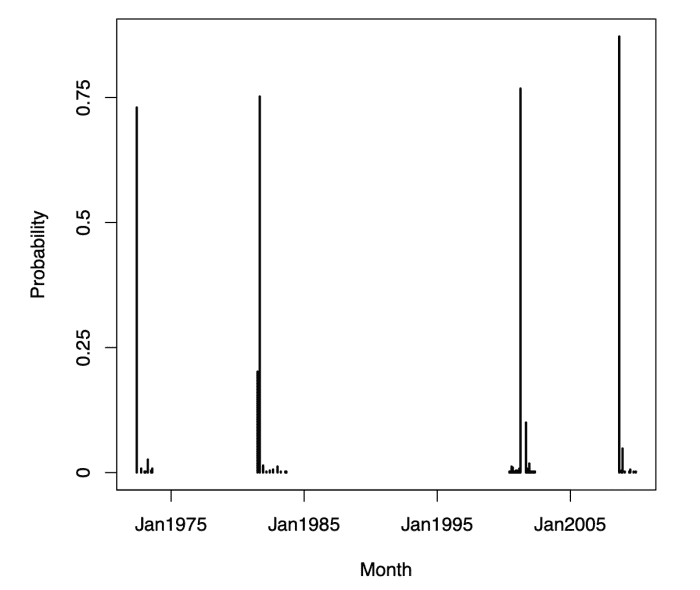

The chart below shows the identified breakpoints for risk premia since 1970. The four “regime changes” happened at the oil price shock in 1972 that triggered the high inflation era of the 1970s, the change in monetary policy by the Fed in 1981 and the switch to interest-rate and inflation targeting under Volcker, the crash of the tech bubble in 2001, and the financial crisis and introduction of zero interest rates in 2008.

Ex-post identified breakpoints in stock markets

Source: Smith and Timmermann (2020)

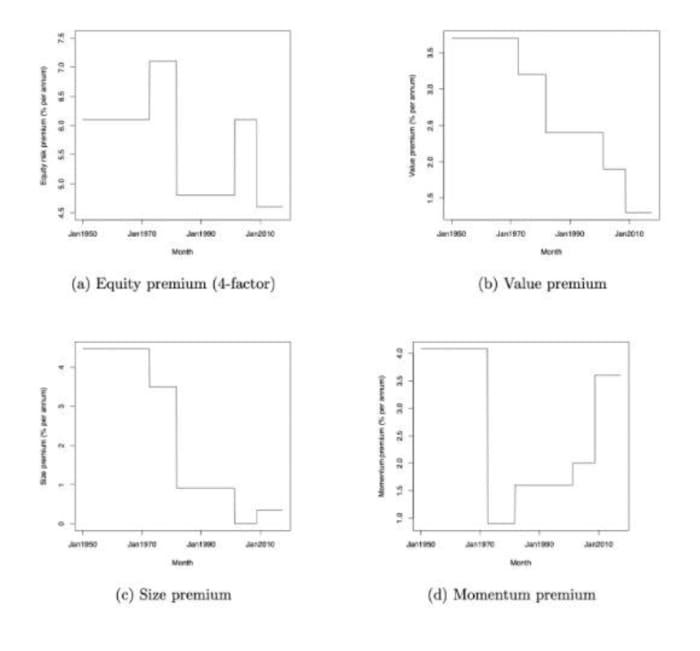

How momentous these events would be for stock markets and investment styles like small-cap or value investing would only become clear years after the fact, but they significantly changed the risk premia earned with these styles as shown in the chat below.

Change in risk premia of different risk factors

Source: Smith and Timmermann (2020)

The risk premium due to equity-market risk (the famous beta of the CAPM model) has basically disappeared since the Fed changed its monetary policy to focus more on inflation and stabilizing the economy. And where there is less economic volatility, there is less systematic volatility in share prices and the equity premium disappears. The equity premium got a revival between 2000 and 2010 but that turned out to be short-lived.

The value premium, meanwhile, has lost more and more of its appeal with every breakpoint. Less inflation in the 1980s reduced the value premium. Even after the tech bubble burst, the outperformance of value was not so much due to a resurgent value premium but more to a resurgence of other risk factors that overlapped with the value premium. But ever since central banks have introduced zero interest rates and QE, the value premium has definitely disappeared.

Small-cap stocks

RUT,

meanwhile have stopped outperforming pretty much the moment the size premium was documented by researchers in the late 1970s. It seems that more macroeconomic stability introduced by the changed Fed policies in the early 1980s has led to a shrinking premium for small-cap stocks in the United States since small-cap stocks are typically more sensitive to economic swings.

Instead, what has increased over time is the momentum premium. Markets have started to trend more and these trends have lasted longer and longer, giving momentum approaches to investing an edge and increasing performance.

Of course, the problem with this entire analysis is that we just had another massive shock to the system in the form of a pandemic. We will only know in a couple of years if this has triggered another change in market dynamics and risk premia for value, momentum, and small-cap stocks.

In my view, the best way to invest is to assume that there was no break in market regime, simply because, as I have explained in my 10 rules for forecasting, as an investor, it is never a good idea to assume massive changes or extreme outcomes.

It is tempting to listen to all the people who claim that the world has changed and we are now entering a new era, but in reality, the world changes less than we want to believe, and for investment performance it is usually better to assume that things haven’t changed all that much after all.

To me, this means that while I am optimistic for value stocks in the short term (i.e. over the next 12 to 24 months), I don’t see a bright future for value in the long run.

Joachim Klement is a former chief investment officer who now writes the Substack newsletter Klement on Investing, where this was first published — Is value dead and if so, since when? He is also the author of the free book “Geo-Economics: The Interplay between Geopolitics, Economics, and Investments,” published by the CFA Institute Research Foundation. Follow him on Twitter @joachimklement.