This post was originally published on this site

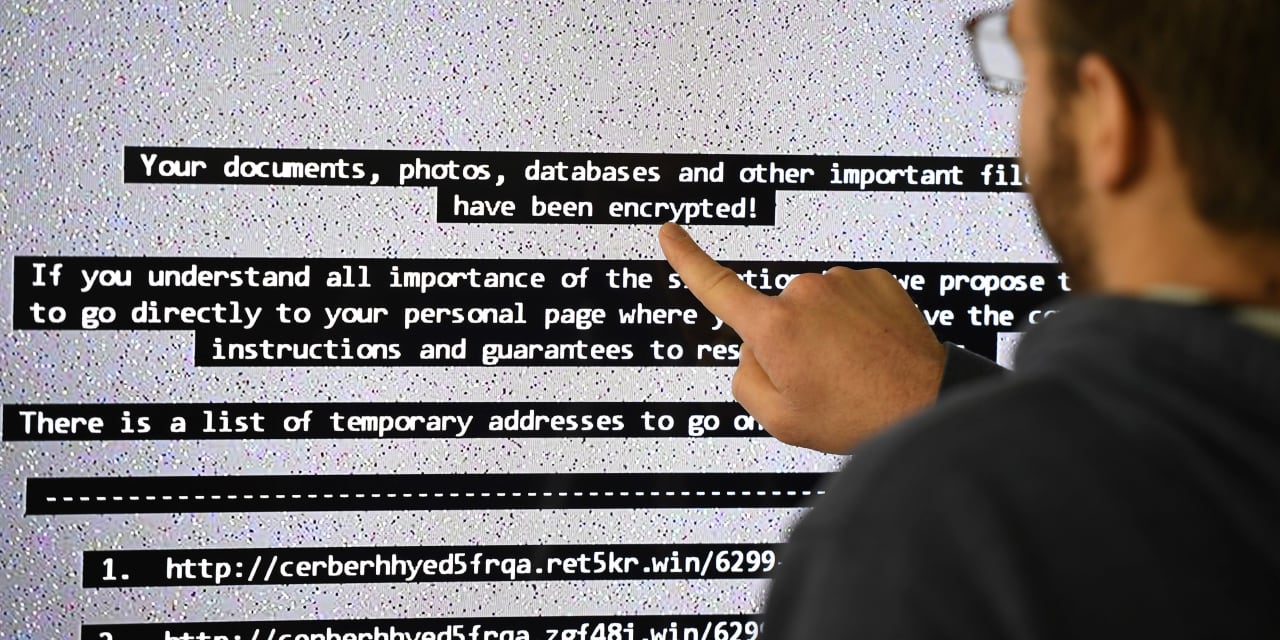

IT-management-software maker Kaseya said in early July it had succumbed to a ransomware attack, which exposed data and compromised over 1,500 companies in its database. What’s worse, the real numbers could be higher, making this one of the largest known supply-chain cyberattacks ever.

This wasn’t the first, nor it will be the last, such attack. However, certain details made cybersecurity experts worried: First, hackers used a zero-day exploit, i.e. a yet unknown flaw in the code, to execute their attack. Second, they targeted a company that isn’t as valuable a target as a bank, for example, but has a strategic significance due to its connection with the companies it serves.

According to experts, independent hackers are upping their game, employing advanced tools and strategies, acting like elite government-backed hackers, rather than mere criminals.

While I don’t necessarily disagree with this assessment, I can’t help but wonder if these experts have underestimated the global hacker community? Also, it is as if they’re not aware of the state and rapid growth of global data infrastructure.

Globalization and unification

We live in the era where digital globalization and unification have reached the highest levels in history. In addition to some benefits, this also brought multiple risks to the table.

One is centralization. Instead of having a decentralized structure that is fragmented across multiple nodes, the data is often stored in a unified system, which means there is a singular point of failure. When that system gets breached eventually, the attacker can gain access to more information and power than he would’ve had if he had accessed a walled-off segment of the same system.

This is especially the case with cloud-based services. The monopoly power of tech giants and service providers growing across the developed world is another pain point as it ensures that a handful of companies provides services to the vast majority of enterprises that share a unified infrastructure and software backbone.

While it may not be obvious to those less tech-savvy, it’s quite easy even for a newbie hacker to discern what operating system (OS), content management system (CMS), marketing technology (martech) platform or other point of entry his victims use, and what kind of vulnerabilities — if any — exist for the version the victim is currently using.

All that’s left is to execute the attack and cover his tracks.

Social engineering

Finally, one must never underestimate the power of social engineering; this approach is superior to any other as it provides access to valuable information regardless of the failsafes in place. If anything, experience has taught us that no system is impervious to hacking.

This also means that the endgame shouldn’t be to make a system “unhackable.” Rather, the goal should be to limit and mitigate the damage that could result from a possible breach.

Placing countermeasures that make hacking more trouble than it’s worth is a better tactic than enticing hacker with huge vaults of digital treasure. Instead of relying on “good old Windows” or WordPress, one should use lesser-known, or even bespoke, operating systems and software whose exploits aren’t publicly available.

But these investments require knowledge and additional funds, and companies are either reluctant, unqualified or incapable of making the necessary move.

However, there is more that companies can do to protect their data and network.

Zero trust

Earlier in the article, I mentioned the significant benefits of decentralization and fragmentation of the IT infrastructure as the best means for mitigating malicious attacks. Both of these features are hallmarks of the zero trust principle.

The main concept behind zero trust is that devices should not be trusted by default, even if they are connected to a managed corporate network such as the corporate local area network (LAN) and were previously verified. Every device within the network should have access only to necessary software and infrastructure — e.g., only an accountant’s computer should have access to accounting software.

This way, a hacker needs to overcome a lot of hurdles, authenticate multiple times and sidestep many security procedures to complete his task — and even then, data he gains access to is limited to what the hacked entity was privy to.

The beauty of this approach was best demonstrated when hackers gained access to the Verkada cameras used in Cloudflare

NET,

offices. As the chief technology officer of the company said on the corporate blog:

“To be clear: This hack affected the cameras and nothing else. No customer data was accessed, no production systems, no databases, no encryption keys, nothing. Some press reports indicate that we use a facial recognition feature available in Verkada. This is not true. We do not.

“Our internal systems follow the same zero trust model that we provide to our customers, and as such our corporate office networks are not implicitly trusted by our other locations or data centers. From a security point of view, connecting from one of our corporate locations is no different than connecting from a non-Cloudflare location.”

The chain is as strong as its weakest link. By applying zero trust principles, the network architect assumes every link is the weakest one. In this case, it was the Verkada cameras.

However, even with a zero trust model in place, a hacker could still get his hands on valuable information, such as customer data.

Big data companies like to use (and abuse) the data provided to them by their customers and users, and rarely implement adequate measures to protect it. Hackers are very much aware of this negligence, and are all too happy to help themselves to stored credentials, which have an enormous value not only on the black market, but also for subsequent phishing and social engineering attacks.

So let’s add one more item to the list: Companies need to make sure consumer data is encrypted, and in the spirit of zero trust principles, is used and accessed on an as-needed-basis and in an encrypted state whenever possible.

Good hackers?

However, the story about hacking does not end here. By now we’ve learned that hacking = bad. But are there scenarios where hacking might actually be a good thing? Furthermore, do we really need unhackable systems in this day and age?

In a world growing increasingly authoritarian, it would be ill-advised to strive for an infrastructure impervious to scrutiny and whistle-blowers. While companies and government organizations may not like to remain vulnerable, gaining unauthorized access to critical information is imperative in case these organizations overstep their boundaries, which has often and repeatedly happened throughout history.

Edward Snowden’s act of social engineering lifted the veil and exposed damage that the National Security Agency (NSA) did to the personal freedoms of Americans. WikiLeaks and others gave the public the necessary insight into the works and actions of elected officials and organizations. Media organizations have done the same over the years, exposing corruption.

This kind of unauthorized access allows for bottom-up control and should always be a welcome sight for the truth-seekers and individuals who refuse to blindly trust everything governments and companies do or say in their effort to rule and not serve the citizens. Having these kinds of failsafes is the last-resort protection against tyranny and, as such, should be a desirable weakness in the eyes of the average person.

Now, perhaps, more than ever.

What is your take on recent hacks? Does your company or the company you work at employ any of the countermeasures mentioned in this article? Let me know in the comment section below.