This post was originally published on this site

Retirees should continue betting that inflation’s recent spike will be transitory.

I concede that this is getting harder to do, however. I first made this argument two months ago in response to the report that April’s Consumer Price Index’s 12-month rate of change was the highest in 13 years. Since then the CPI has risen even more, and its latest 12-month rate of change is now higher than it was then.

For this column I’m adding an additional perspective to the arguments I advanced then. As far as I can tell, it hasn’t been included in the myriad discussions that have taken place up until now.

Read: Planning for retirement? You should also plan for inflation

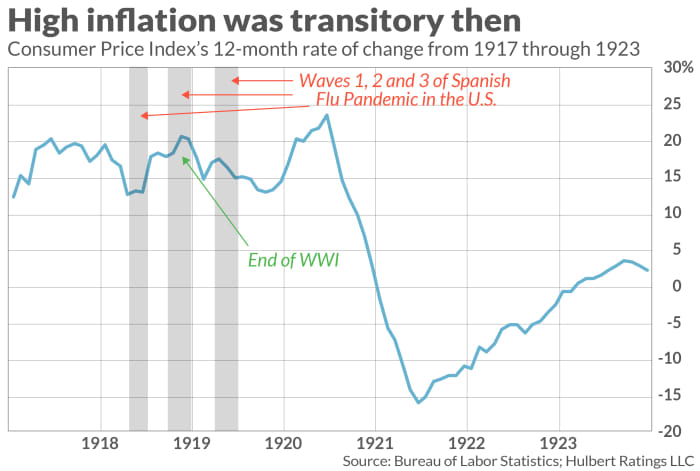

This additional perspective comes from analyzing how inflation responded a century ago when the Spanish-flu pandemic came to an end. This history is relevant, since Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell this week argued that inflation has spiked upward because of “production bottlenecks” and “supply constraints” caused by the economy opening up after the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns.

The Spanish Flu pandemic a century ago provides the ideal laboratory for testing Powell’s argument. Did inflation spike upward as the economy emerged from that pandemic? And, if so, was it merely transitory?

Read: What inflation means for your retirement

The accompanying chart provides an answer. It plots the Consumer Price Index from 1917 (before the pandemic started) until 1923 (well after its end). Sure enough, the CPI spiked upward after that pandemic’s third and final wave came to an end. After spiking, however, the CPI’s 12-month rate of change plunged. By mid-1921, in fact, there was double-digit deflation, when the CPI was 15.8% lower than where it stood in mid-1920.

To be sure, there was a lot else going on in the world in the early 1920s, which is why history at best only rhymes rather than repeats itself exactly. World War I had just come to an end, for example, and the redirection of the economy from war production to consumer goods no doubt exacerbated supply shortages and bottlenecks.

But the overall pattern is clear, and it supports the current “inflation is transitory” argument. In fact, the century-ago experience suggests we might want to be worried about economic weakness, if not an outright recession, in the next year or two.

This perhaps helps to explain why interest rates have come down even as the CPI’s 12-month rate of change has risen. The Treasury’s 10-year yield, for example, is currently 0.4 of a percentage point lower than where it stood in March—even though the CPI’s 12-month rate of change over this same period has risen by 2.6 percentage points.

In an early June column, I mentioned an inflation forecasting model maintained by the Cleveland Federal Reserve that, according to my tracking, has one of the better historical track records. Its latest forecast, updated after this week’s unexpectedly large jump in the CPI, is that inflation over the coming decade will average 1.61% annualized. That’s well below the Fed’s widely-advertised 2% inflation target and well below the CPI’s latest 12-month change of 5.4%.

To be sure, many monetary experts and academic researchers disagree, insisting that inflation’s recent spike is more than just transitory. So there are no guarantees. Still, I think it is relevant that the last time our economy emerged from a pandemic, inflation spiked only temporarily and then plunged.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com