This post was originally published on this site

After a nightmare year for French vineyards in which the pandemic saw revenues plunge and winemakers forced to send their unsold wine to distilleries, sometimes to be turned into hand sanitizer, the sector is trying to bounce back.

In Bordeaux, the epicenter of the global fine wine market, the wine harvested during that difficult time has just been through its en primeur campaign, often known as “wine futures” in English.

The en-primeur system dates back to the 18th century, and was modernised in the 1970s to resemble what we know today. Similarly to futures on financial markets, it allows producers to sell their wine while it is still in the barrel. The wine is then finished, bottled and delivered to customers around two years later.

This campaign is run as a finely organized system. Every year, over a week in spring, wine experts will come to Bordeaux to taste the wines and publish their notes and scores. This is followed by a two-month period during which each chateau sells its wine to consumers via an intricate system of brokers, traders and merchants.

This well-oiled machine is nevertheless subject to much uncertainty, which goes beyond the current pandemic. That’s because en-primeur sale involves an unfinished vintage of uncertain quality released into an unknown future economy.

How do wine sellers put a value on this unfinished wine? And what is a fair price for a vintage like 2020? We built an economic model to simulate reasonable release prices for the current campaign.

Previous campaigns

In Bordeaux, demand and, therefore, prices depend mainly on quality and less on quantity. Following a price decline between 2011 and 2016, the Bordeaux market rebounded in 2016 due to a great 2015 vintage. This was followed by an even better 2016, for which prices increased substantially but not excessively.

In 2017, vineyards were hit by a severe frost which caused a 40% drop in the wine harvest. Lower quantities encouraged châteaux to maintain prices close to 2016 despite the quality. Poor sales thus unsurprisingly characterised the 2017 en-primeur campaign.

The 2018 vintage, sold as exceptional, saw significant increases, even though price levels were already very high. While the quality should have generated solid demand, this was not the case – the fault of the châteaux for being too greedy.

Last year, the pandemic and associated lockdowns almost led to the cancellation of the en-primeur campaign for the 2019 vintage. In the end, a postponed, shortened version took place. Perhaps surprisingly, and thanks to exceptional quality and reasonable prices, it was a success.

The pandemic forced the châteaux to make an effort on prices. Here lies the difficulty of this market: sellers had to lower prices to ensure a successful campaign while also being careful not to send too strong a signal to the market at the risk of making the many wines of 2017 and 2018 that were still available unsellable.

Back to normal?

The 2020 vintage benefits from more favorable external conditions than 2019, but it is hard to speak of normality yet. This year, tastings took place remotely with samples sent to experts around the world. Tasters and producers met on video calls.

Meanwhile, restaurants in France were completely closed between October 2020 and June 2021 and are only just getting back into business. Uncertainty about the economic recovery remains high.

Still, the situation has improved since last year, fine wine prices have remained solid, and the quality of the 2020 vintage looks excellent. There will be a few great wines that will be the market’s main focus when they are released. But we do not know how the market will react to this unique succession of three excellent vintages in a row. This is unprecedented and raises the question of the market’s capacity to absorb such a considerable volume of high-quality wine so quickly.

How to determine a fair price

In a forthcoming study, we proposed a model to estimate the fair price of 69 prestigious Bordeaux wines at the time of their release. The approach considered is based on the principle that prices on the primary markets (en-primeur) and secondary markets (bottles from past vintages) cannot be substantially different.

The model includes variables measuring the economic situation, the quality of the vintage and of the wine concerned, and its volatility (some wines have stable prices whereas others fluctuate strongly).

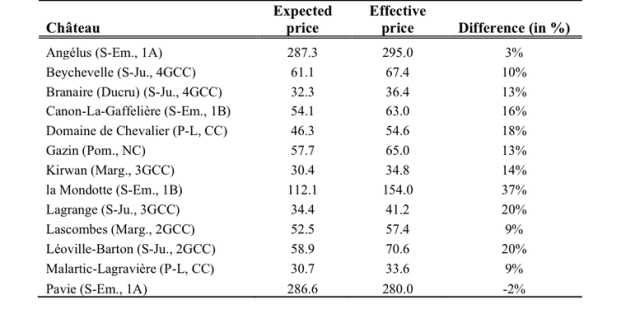

Below we use this model to estimate the fair prices of these wines for the 2020 vintage and compare them to those already released in the en-primeur market before June 7. The model allows us to explain around 80% of the price variations of these wines.

The model suggests that a price stabilization relative to the 2019 vintage would be reasonable. And considering the exceptional circumstances surrounding the release of the 2019 vintage, a slight increase (in the order of 5% to 10%) in prices over 2020 compared to 2019 would seem logical.

This table shows the fair release prices – according to our model – and contrasts them with the actual prices for wines, both in euros. All but one of the wines were released at prices above what the model predicts. But the differences are often reasonable.

Jean-Philippe Weisskopf, Philippe Masset.

Yet some wines seem very expensive compared to our model’s prediction, including Château La Mondotte from the famous Saint-Emilion region and Léoville-Barton and Lagrange from Saint-Julien. Some wines that had drastically lowered their prices last year have not increased much this year. This is the case of Malartic-Lagravière in Pessac-Léognan, which, after a drop of more than 20% last year, is content with a 9% increase this year.

At this stage, most of the price increases for the 2020 vintage remain moderate, which is consistent with the model. It suggests that the most significant price increases relative to the 2019 vintage should not exceed 10%, except for a few wines such as rare Pomerols and some of the first growths.

Of the wines that have already finished the en-primeur campaigns, some have increased their prices beyond the suggested threshold. Early market signs suggest that the increases are excessive and have reduced demand for these wines.

With the influx of great vintages in Bordeaux and elsewhere in Europe, it would be wise for those chateaux yet to release their prices not to be overly greedy and maintain attractive prices to ensure a successful campaign. This would be the best way to bring Bordeaux bouncing back after the pandemic.

Jean-Philippe Weisskopf is an associate professor of finance at the École hôtelière de Lausanne, Haute école spécialisée de Suisse occidentale (HES-SO) in Delemont, Switzerland. Philippe Masset is a Professeur associé at HES-SO. This was first published by The Conversation — “How Bordeaux winemakers are setting their prices after the pandemic“.