This post was originally published on this site

With most coronavirus pandemic regulations lifted in the U.S. and hotels seeing a resurgence of visitors, many hotel employees have returned to work. But not all.

Hotels have cut back on daily room cleanings, which means many housekeepers remain on call. Because of this, a union that represents hotel service workers is sounding an alarm and saying that nearly 40% of hotel-housekeeping jobs — more than 180,000 — are in danger of being permanently eliminated.

“Every time there’s a crisis, companies try to use it to hurt workers,” Unite Here International President D. Taylor told MarketWatch.

Executives of some of the nation’s biggest hotel chains, including Hilton

HLT,

Marriott

MAR,

and Hyatt

H,

have signaled that pandemic-induced changes may become the norm. Some of those changes could result in fewer hotel employees and diminished offerings for hotel customers, including room cleaning, room service, complimentary breakfasts and other food service.

A Hilton spokesman said daily cleaning remains an option at all of the company’s hotels, but that it has “seen different types of demand for housekeeping during the pandemic. Some guests have preferred to access a sealed room and then be the only ones entering that room for the duration of their stay. Others have preferred daily housekeeping.”

The cutbacks may be related to the pandemic, but the hotels are also using them to soothe investors. Christopher Nassetta, chief executive of Hilton Worldwide, said on the company’s earnings call in November that he expected cost savings such as furloughs and workforce reductions “should be semi-permanent.” On the other hand, he said during the earnings call last month in response to a question about reported staffing shortages that “you just can’t get enough people to service the properties.”

See also: Is that Airbnb too expensive? CEO plans ‘systematic update on pricing’ as travel recovers

That doesn’t seem to be the case at Hilton Hawaiian Village, where Nely Reinante is a housekeeper and is waiting to go back to work full-time. Furloughed since March 2020, she recently told MarketWatch her hotel has made daily room cleaning optional, which means she remains on call. Unite Here said Reinante’s hotel has brought back about 450 of its 620 housekeepers.

Reinante said she has worked just one day a week so far. Though she appreciates being back, it’s not enough. She also needs health benefits for her and her family, including a 9-year-old daughter who has medical issues. She can’t get those health benefits unless she works at least 20 hours a week.

“I hope that we’re going to get called every day,” she said. “I’m trying to stay positive.”

A spokeswoman for Hilton said “the vast majority of housekeepers at Hilton Hawaiian Village have been recalled to their roles, though hours and shifts may vary based on business demand as the industry recovers.” As for food service, some Hilton hotels switched to “grab and go” options or food and beverage credits at the beginning of the pandemic instead of buffet breakfasts, and are now in various stages of reintroducing different standards.

The Airbnb effect: Travelers are booking trips online again, but they mostly want the same thing — not a hotel

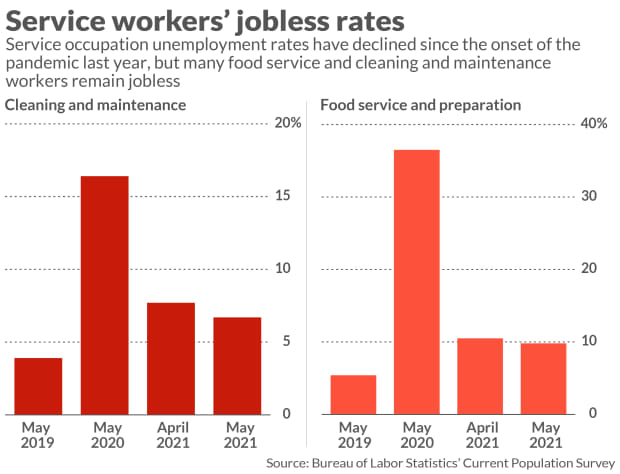

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the nationwide unemployment rate for cleaning and maintenance workers in May was at 6.7%, while the rate for food preparation and service workers was 9.8%. While those rates are an improvement from a year ago and even a month ago, they are still far higher than rates from before the COVID-19 pandemic, and it’s clear that some workers’ situations — even if they have returned to their jobs — are far from ideal.

Some hotel housekeepers complain that the scaling back of daily cleanings has made it harder for them to do their jobs. Andee Huang-guan, a housekeeper who went back to work at the Westin Boston Seaport District hotel in October, told MarketWatch that her hotel recently resumed daily cleanings, but that before that, having to clean mostly “checkout rooms” — rooms that guests had stayed in for several days and then checked out of — was a big pain.

“It’s a lot more cleaning inside,” she said, describing stained glasses or cups and adding that she was having to use more chemicals. “Sometimes I could not finish my assignments. I had to work faster.”

Huang-guan also said she had to take pain medication, and some of her colleagues “are having to do physical therapy” because of the added stress to their bodies. She said going back to daily cleaning will be easier for her and her colleagues, and will benefit the hotel guests, some of whom have asked her about the changes.

“Every day, guests said ‘nobody is cleaning my room,’ ” she said.

Huang-guan’s hotel is operated by Aimbridge Hospitality under a franchise agreement with Westin, a brand that is owned by Marriott. When reached for comment, Aimbridge said: “We follow all the brand guidelines as it relates to safety, cleanliness and all other COVID protocols.”

The hotel is owned by DiamondRock Hospitality Co.

DRH,

a real-estate investment trust. During DiamondRock’s earnings call last month, executives were asked about whether lower staffing levels are affecting guest satisfaction. Chief Operating Officer Thomas Healy said, “we’re making sure that the positions that add value and prove customer experience and touch the customer, those ones are the ones that go back first.”

Read: COVID-19 hit the hotel industry hard. Here’s how hotels are pivoting in the new reality

A report published by the American Hotel & Lodging Association in January showed that guests ranked enhanced cleaning and hygiene practices as the second most important factor in their choice of hotels, behind price. That means workers like Reinante and Huang-guan, who are immigrants from the Philippines and China, respectively, are responsible for an important part of customer satisfaction.

If they lose their jobs or don’t get back to full-time work, they are part of the “exact same communities that have been hurt and most affected by the pandemic,” Unite Here’s Taylor said. “It’s like a double whammy.”

Seventy-three percent of U.S. hotel housekeepers are Hispanic or Latino, Black, Asian American or Native American, according to Unite Here. Two out of three of those groups were disproportionately affected by the pandemic. Adjusting for age differences, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has estimated that Native Americans, Latinos and Black people are two to three times more likely than white people to die of COVID-19.

Meanwhile, a McKinsey report finds that as the economy recovers from the pandemic, demand for high-wage jobs may grow but that demand for service occupations and low-wage jobs may decline through 2030.

Taylor also said hotels cutting housekeepers and other services could lead to safety issues. He called housekeepers a possible first line of defense in bringing safety concerns to hotel management’s attention.

“The union’s going to fight back,” he said, but added that customers might want to try to do their part to preserve what they have come to expect from the hospitality industry. “They should insist they want their room cleaned, have room service and want to feel safe.”

For more: What could save the hotel industry amid the pandemic — a hub for work and play

Reinante said she and her colleagues have passed out leaflets telling guests the situation at her hotel in Hawaii. She said many of them are surprised that daily cleaning is no longer the regular practice.

“It affects their overall experience at the hotel,” she said. “The guests are here to enjoy. We’re proud of the beauty of our island.”