This post was originally published on this site

It’s time to hire a dog walker, and change out of your Lululemon

LULU,

sweats.

That’s the message JPMorgan Chase’s chief executive, Jamie Dimon, has sent employees. In a memo signed by Dimon and sent to employees this week, the company said that it was mandatory for all employees to disclose their COVID-19 vaccination status by June 30, and that employees should return to the office by July 6.

Those who are unvaccinated or choose not to answer the vaccination question will have to wear a mask, adhere to social-distancing guidelines and get tested for COVID-19 weekly.

Along with Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs

GS,

JPMorgan wants workers to prepare to return to their desks this summer. Employees, meanwhile, may feel like they’ve been given a proverbial puppy of remote work — as well as perhaps adopting a real one during the pandemic — only to have it taken suddenly away.

Dimon did not mince his words. Working from home “doesn’t work for people who want to hustle, doesn’t work for culture, doesn’t work for idea generation. By September it will look just like it did before,” Dimon said at a Wall Street Journal CEO Council event last month. “We are getting blowback about coming back internally, but that’s life.”

The company has called for a minimum of 50% occupancy, and in some cases 100% occupancy, depending on the department and the roles involved.

“

‘Remote work raises questions about public health and work-life-balance, but finances determine where people can live and work.’

”

JPMorgan is playing a zero-sum game with its staff: They’re either all in, or they’re all out. When asked — yes, it doesn’t hurt to ask — most employees recognize the importance of being present to brainstorm with colleagues and form creative teams, but they also overwhelmingly prefer some kind of hybrid format.

Millions of people thank their lucky stars that they still have a job, and couldn’t care less whether they do it in person or remotely, in their pajamas or chinos and a blue shirt. But the radical change of scenery over the last 16 months has also led people to re-evaluate the cost of childcare, their work-life balance and their career aspirations.

There is more understanding and nuance in JPMorgan’s back-to-the-office memo that was missing from Dimon’s more provocative proclamations. Some employees will work five days a week on site; others will spend a minimum of 50% of their time in the office due to occupancy limits.

“We are aware that some teams are piloting a hybrid approach that varies by job, such as three days in the office or 50% rotations, but we want each of you back regularly so that we can test the effectiveness of these models as quickly as possible,” the memo said.

This conversation is so much bigger than JPMorgan. But the biggest U.S. bank provides as useful an entry point as any corporation. Not everyone can afford to live in places like New York City, where JPMorgan

JPM,

is headquartered, or Seattle or Los Angeles, or many of the major U.S. corporate hubs.

Dimon, after all, received a compensation package of $31.66 million last year, up from $31.61 million in 2019. He’s well remunerated and in a privileged position, even more so than most of those who have the option to work from home. When the stationery cupboard is bare, no one will ask him if they can borrow his stapler.

The office idyll, a place for learning, networking and brainstorming.

Getty Images

Racial wealth gap

Dimon has stressed the importance of coping with the U.S.’s racial wealth gap, and he has pledged to address working conditions and burnout in the bank’s ranks. But insisting people return to the office — so bluntly and so soon, with the U.S.’s adult vaccination rate having only in late May crossed the 50% threshold — arguably only threatens to exacerbate that gap.

About that racial wealth gap. Remote work raises questions about public health and work-life-balance issues, but finances determine where people can live and work. The millions of job losses at the peak of COVID-19 pandemic hit Black and Hispanic Americans more than white Americans, research shows.

Their work was also less likely to be virtual, or mobile. What’s more, those who had to travel to their place of work reported a greater deterioration in working conditions. Opening up more locations for employees also opens companies up to more diverse applicants.

“

‘If you can go into a restaurant in New York City, you can come into the office.’

”

“If you can go into a restaurant in New York City, you can come into the office,” Dimon’s fellow banking CEO, James Gorman of Morgan Stanley, who was paid $33 million last year, told a company conference this month.

That headline-grabbing quote aside, Gorman also said that more junior employees learn in the office. Last week, he told CNBC that he himself started off with two to three days a week on site, and gradually upped it to three or four. But he also said that New York jobs come with New York salaries.

Morgan Stanley

MS,

employees, in one significant difference from their peers at JPMorgan, will need to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 before they can return to offices in New York. All staff are required to attest their vaccination status by July 1.

A Goldman Sachs memo released last month, co-signed by CEO David Solomon, said: “We are focused on progressing on our journey to gradually bring our people back together again, where it is safe to do so.”

Not all nine-to-five employees enjoy the same luxuries and carefree domestic lifestyles as CEOs. It’s a daily juggle and struggle. Escaping to the suburbs can save families hundreds of thousands of dollars over a lifetime. The median cost of a home in New York City hovers at $675,545, according to Zillow

ZG,

America’s greatest cities will never be easy or inexpensive places to live. After a pandemic-related great migration out of urban centers, the median sale price of homes in cities was up 16% in February on a year-over-year basis, surpassing the price increases in the suburbs for the first time since the onset of the pandemic, Redfin said in March.

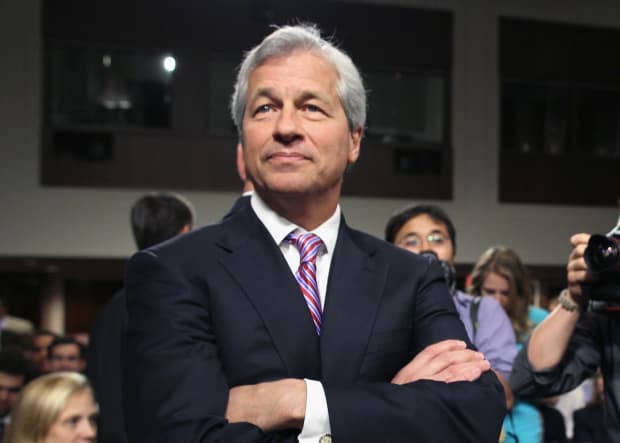

President and CEO of JPMorgan Chase Co. Jamie Dimon earned $31.66 million last year.

Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Workplace revolution

Do we have the next workplace revolution within our grasp, one that perhaps rivals the industrial revolution and the digital revolution? Is this the next natural, if not inevitable, step?

Chris Herd, the founder and CEO of Firstbase, which helps companies transition to remote work, said he thinks so. Or would like it to be so. He said he prefers the term “work communities” over “corporate culture,” a concept often used to herd the army of clockwatchers back to the mothership.

When I asked Herd about the ability to cast the hiring net wider and recruit a more diverse workforce during an interview on Barron’s Live last week, he said: “What we’re talking about is enabling access to opportunity to everyone. How can we create companies that are great places for single parents to work, or people who are caring for other family members, or people with health conditions or impairments?”

“

‘How can we create companies that are great places for single parents to work, or people who are caring for other family members?’

”

“The question I always get is, ‘What happens to those jobs?’ The obvious answer is remote workers still buy coffee, we still go to restaurants — if anything, we actually do that more,” Herd said. “We just do it locally. Rather than do it at the bottom of some faceless high-rise in New York, we buy it from people locally.”

The one reason employers are reluctant to allow people to work from home, even for a portion of the week, often comes down to trust. It needs to be tested in order to be proven wrong. Has the pandemic — for better or for worse — not already achieved that?

The jury is out on how many lightbulb moments take place during long conference-room meetings or chance encounters while rummaging for your packed lunch in the office refrigerator — assuming last night’s tofu curry has not already been snaffled by an anonymous coworker.

In fact, when companies switched to open-plan offices — presumably designed without increased demand for noise-canceling earphones in mind — researchers reported in Harvard Business Review that face-to-face interactions actually fell by 70%.

Herd, perhaps unsurprisingly, is not swayed by the argument that businesses will pay a price for all those lost moments of brainstorming by the office water cooler. He calls offices “instantaneous gratification distraction factories” where synchronous work is impractical and, in fact, often make it impossible to get stuff done.

Morgan Stanley Chairman & CEO James Gorman received $33 million in compensation in 2020.

Mandel Ngan/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

Postprandial dip

And then there’s the notorious postprandial dip, easily solved at home by a 20-minute nap on the sofa followed by a brisk constitutional in the local park. A paper in the Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine has this to say about that midafternoon productivity black hole.

“The post-lunch dip is a real phenomenon that can occur even when the individual has had no lunch and is unaware of the time of day,” the researchers concluded. “This dip has its roots in human biology, and may be linked to the size of the 12-hour harmonic in the circadian system. It is certainly exacerbated by a high-carbohydrate lunch, and may be more likely to occur in extreme morning-type individuals.”

So who gets ahead in America’s corporate culture? Who are all of those open-plan offices and transparent glass conference-room walls built for? “It’s the louder, more gregarious people who benefited disproportionately from the office,” Herd said.

“

‘Real-time work occupies a fertile and critical place in our work lives. But Dimon did not help the cause with his inflammatory comments.’

”

“They would go into meetings and share their views in a more forthright way than other people would,” he added. “The office has been great for a few people. Remote work can be great for many people.”

There are many questions that need to be answered about remote or virtual work. But we also shouldn’t forget that it’s a privilege not afforded to most frontline workers in hospitals, in the service industry, in retail and, yes, at the bank branch. They should be both appreciated and applauded.

But there is momentum for a different approach to work that can be done remotely. As Joseph Davis, Vanguard’s global chief economist, asked last December: “If tech workers can just as easily do their jobs from home offices in Toledo or Tulsa or Topeka, do Silicon Valley firms need vast California campuses?”

There is much to be said in favor of real-time work and interaction. As the JPMorgan memo pointed out, working virtually is easier when people have established relationships, but remote work makes it harder to train new employees and develop new relationships.

“A heavy reliance on Zoom meetings actually slows down decision making because there is little immediate follow-up,” the company’s memo added.

Real-time work occupies a fertile and critical place in our work lives. But Dimon did not help the cause with his inflammatory comments last month: “And yes, the commute, you know, yes, people don’t like commuting, but so what?” He is not, after all, sitting on the Long Island Railroad or Amtrak for an hour or two, each way.

To be clear, people were forced to work from home during the pandemic, juggling other responsibilities like childcare and homeschooling. But imagine a true virtual work life, with time to run a duster over the house, be home for the cable guy, while using that valuable commuting time to make an early start to the work day.

That flexibility would give people room to breathe and, arguably, become more productive by using their time more efficiently. Maybe then we’d get closer to a healthier office idyll of learning, networking and brainstorming. People would show up because they want to, and not because they were strong-armed into it.

No more staring at an office computer screen wishing you were home with your dog, wondering if the air conditioner really does crank up after three o’clock. No more being tasked with the job of ordering stationery. And no more politicking, world-weary coworkers making you wish you’d bought those discounted noise-canceling headphones on Amazon Prime Day

AMZN,

when you had the chance.