This post was originally published on this site

In 2001, some of the country’s biggest public pension systems were flush.

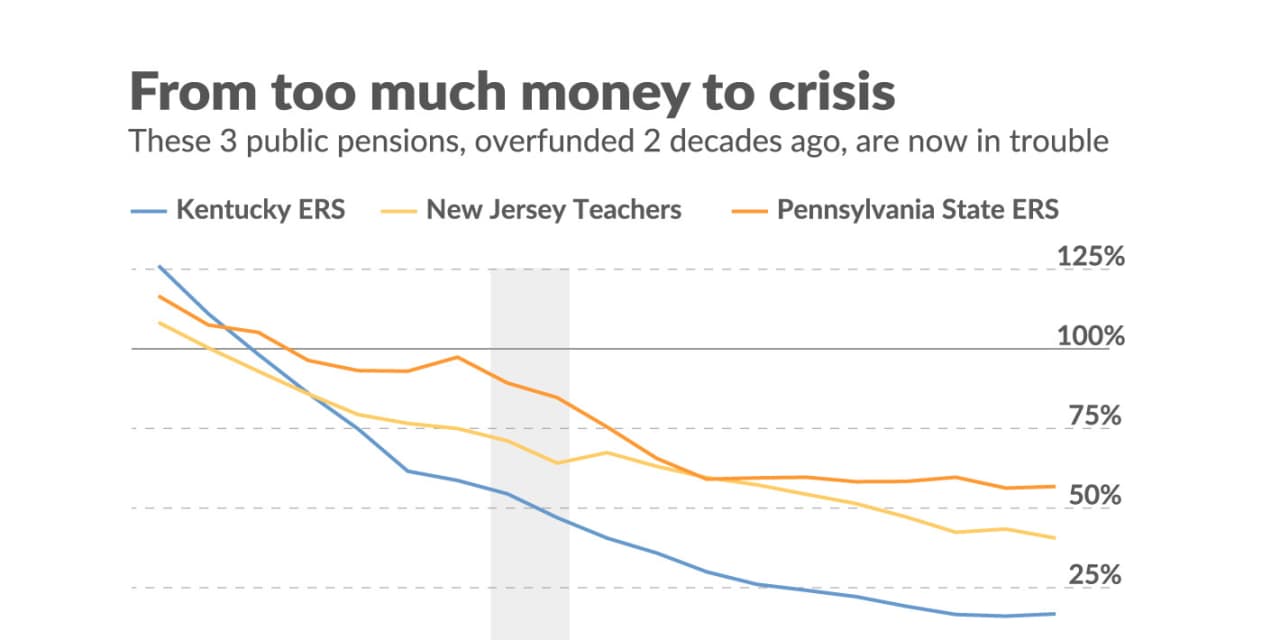

The plan serving Kentucky state workers, for example, was 125.8% funded, meaning it had 25.8% more money on hand to pay all of what it owed current retirees and workers expected to retire for the next 30 years.

But not even two decades later, Kentucky’s pensions, and some other previously over-funded plans, were in crisis. What happened?

In Kentucky, lawmakers approved extra benefits for plan participants — even making them retroactive. There and in other states, legislators decided to skip making necessary payments, freeing up budget money for tax cuts or other expenses. And in every city and state across the country, the financial crisis hit investments hard. At some point, a few careless decisions turned into a crisis.

In 2019, the Kentucky Employees Retirement System was only 16.5% funded, making it one of the worst-funded pension plans in the country, according to data from the Center on Retirement Research at Boston College.

As market returns remain strong, and most states and locals come through the coronavirus crisis much better than hoped, it may be tempting to view public pensions as home free. “Pension Worries Ease for States, Localities on Stimulus, Stocks,” blared a recent Bloomberg News headline.

But the example of Kentucky, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and a few others, shows how critical it has become for sponsors of pensions to be disciplined in sticking to a funding plan — even, or perhaps especially, when the odds seem to be in their favor.

“Well-funded pension systems are an attractive target for both employees and employers to approve additional awards,” said Matt Fabian, a partner with Municipal Market Analytics.

What seems like “extra” money, in other words, can be attractive to raid.

Red flags?

Retirement funds aren’t slush funds, but they can seem that way to governments. Fabian says that temptation is “why I think pension funds are not suitable for political employers. They are a budget gimmick tool.”

Reducing payments or increasing benefits isn’t inherently a red flag, argues David Draine, a senior officer for the Pew Charitable Trusts, as long as “you’re following the rules and doing what your actuaries tell you.”

The problem, Draine said in an interview, is that cities and states often take too much away from pensions when times are good, and when times are bad, it becomes extremely difficult to compensate.

“You can’t treat good news differently than you treat bad news,” Draine said.

It’s worth pointing out that some recent public finance research suggests that the notion of a public-pension crisis is vastly overblown. That’s because the current standards are meant for a system in which municipalities have on hand all the money they’ll need to pay all plan participants for the next 30 years, which some analysts think isn’t necessary.

But the current funding levels for Kentucky, the Pennsylvania State Employees’ Retirement System, at 57%, New Jersey Teachers’ Pension and Annuity Fund, at 40%, and a few others are deeply concerning. Righting the ship gets harder the longer it takes to make reforms: investment returns accrue to a smaller base of assets, for example.

Many struggling states “got into their pension crisis by writing lucrative benefit awards and failing to account for them,” Fabian said.

Now, their pension costs are “higher, maybe materially so,” he told MarketWatch. “The problem is that the employer can backload compensation in an opaque way through benefits that are not immediately priced into the government’s budget.”

Draine takes a more optimistic view. At the start of the pandemic, many public-finance observers were worried about exactly this issue, he noted. “Were states going to take pension holidays because of COVID? This is a once-in-a-generation pandemic, so if you ever wanted to say, this is a good time to not make payments, that’s a story to tell.”

In fact, most lawmakers stayed disciplined, Draine noted, and now are also benefiting from market outperformance and federal stimulus money. In 2020, the S&P 500

SPX,

boomed 18.4%, and in the year to date, it’s gained 13%. Other assets are also benefiting from a global economy that’s coming back to life: the oil price

CL00,

is up 50% this year, for example.