This post was originally published on this site

You can safely ignore almost everything you’ve been told up until now about converting your IRA or 401(k) into a Roth.

That’s not because what you’ve been told is outright wrong. It’s just that, for almost all of you reading this column, a Roth conversion will not make a significant difference to your retirement standard of living.

The almost universal financial planning advice, of course, has been to recommend Roth conversions—paying tax now on your IRA or 401(k) balances in order to avoid paying tax on withdrawals when you’re in retirement. This advice is usually justified by the assumption that tax rates are headed higher. Many currently think that assumption is a no-brainer, on the grounds that President Biden is looking anywhere and everywhere for ways to raise money to pay for his multi-trillion dollar infrastructure program.

According to an exhaustive new study, however, only if you’re in the top 1% of retirement savers will a Roth conversion move the needle more than a little bit in your retirement. The study, “When and for Whom Are Roth Conversions Most Beneficial?,” was conducted by Edward McQuarrie, a professor emeritus at the Leavey School of Business at Santa Clara University. Unlike many previous analyses of Roth conversions, McQuarrie adjusted all his calculations by inflation and the time value of money, likely changes in tax rates, and a myriad other obvious and not-so-obvious factors.

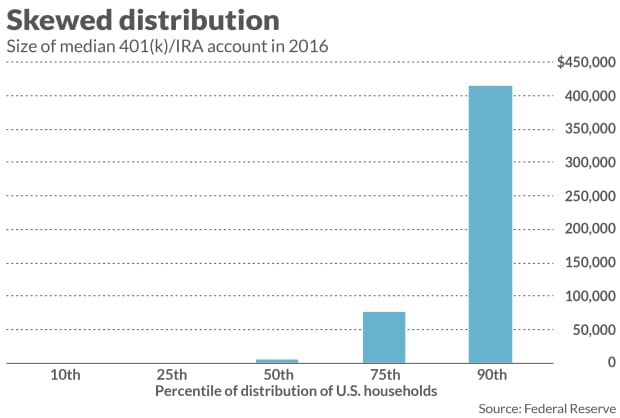

McQuarrie finds that only if you have millions in your IRA or 401(k)—at least $2 million for an individual and $4 million for a couple—will your required minimum distributions in retirement be so large as to put you into even the middle tax brackets. Only for those select few will the potential tax savings of a Roth conversion be significant. For most of the rest of us, we’ll likely be in lower tax brackets in retirement years, with an effective rate of 12% or less. That almost certainly will be lower than the tax we would pay for a Roth conversion during our peak earning years prior to retirement.

As McQuarrie said in an interview: “It is surprising how many millions of dollars you have to have piled up before you will even reach the current 24% bracket.”

Even if tax rates themselves go up, furthermore, it’s still likely that your tax rate in retirement will be lower than preretirement. That’s because you’ll likely be at your peak earning years prior to retirement, when you might be undertaking a Roth conversion, and therefore in a relatively high tax bracket. Once you stop working and retire, and are living on Social Security and the withdrawals from your retirement portfolio, your tax rate will most likely be lower—even if the statutory tax rates themselves have been increased in the interim.

In the long run we’re all dead

Note carefully, however, that even when your retirement tax rate is lower than your preretirement rate, a Roth conversion will still pay off—eventually. The key, McQuarrie explained, is how long it takes to do so, and whether you’ll still be alive. In some of the scenarios he investigates, the Roth alternative doesn’t produce a greater amount of total after-tax wealth until we’re close to 100 years old, if not older.

McQuarrie said that the more helpful way to think about a Roth conversion is not in binary terms of good or bad but instead to calculate how long it will take for the conversion to pull ahead of a traditional IRA or 401(k). He said that he suspects many, if not most, of you will be surprised by how long it takes. He also thinks you’ll be surprised by how little benefit you’ll receive from a Roth conversion, even if you live long enough.

For both reasons, he added, if you are in poor health, and/or have a family history of shorter life expectancies, then you might not want to even bother with a Roth conversion.

When Roth conversions make the most sense

To be sure, McQuarrie added, it’s easy—on paper—to come up with scenarios in which a Roth conversion makes a lot of sense. One scenario in which it pays off quickly and strongly is when you can arrange to take the conversion in a year in which you are in the zero tax bracket. In that event, of course, your future withdrawals will almost certainly be subject to a higher tax rate.

This is a relatively rare scenario, of course. It requires that, for the year of the conversion, your entire living expenses be covered by income from nontaxable sources. Few of us fit into this category, of course. Furthermore, note carefully that your conversion in such a year must be kept small enough to not bump you up into higher tax brackets. At current rates, for example, that means less than $100,000 for an individual, and less than $200,000 for a married couple.

Notice the dilemma into which this puts Roth cheerleaders when devising a hypothetical scenario to make their case. On the one hand, they have to focus on a retiree with millions of dollars in a traditional IRA or 401(k), since only in that case do tax rates in retirement become a concern. On the other hand, in order for such a retiree to take advantage of a Roth conversion at the lowest tax rate, only a small fraction of the retiree’s IRA or 401(k) can be converted.

As McQuarrie puts it: “For affluent professionals, Roth conversions are a game played at the margins.”

The penalty for early withdrawals

McQuarrie also emphasized that the eventual benefit of a Roth conversion is dependent on not using the converted portfolio for annual withdrawals in retirement. That’s because a Roth comes out ahead of a traditional IRA or 401(k) only through the power of compounding over many years—if the amount that is converted is left untouched, in other words. Otherwise you sabotage that compounding process.

You should therefore consider a Roth conversion for a one-time lump sum withdrawal later in retirement (such as a down payment on entering a nursing home) or what you anticipate leaving as a bequest.

The bottom line: For most of us, there are far more important issues to focus on than whether or not to undertake a Roth conversion.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com