This post was originally published on this site

The rising cost of living — a.k.a. inflation — has surged at its highest rate in more than a decade as the U.S. economy fully reopens. How high will it go? And how long will it last?

Read: U.S. consumer prices soar again and push CPI inflation rate to 13-year high

These questions are unlikely to be answered for many months or longer, but MarketWatch is, well, keeping watch. Check out our new inflation tracker, which we began publishing with the May report on consumer prices.

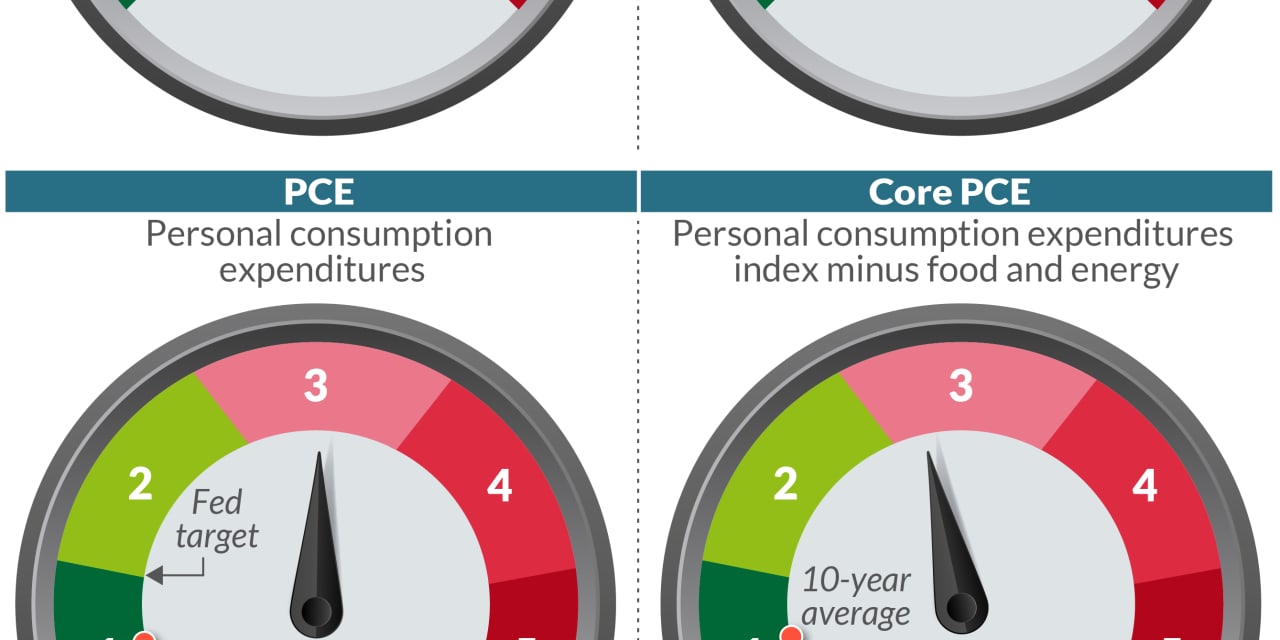

The tracker shows the current rate of inflation for the four price barometers that are most closely followed by Main Street, on Wall Street

DJIA,

and in Washington.

The Federal Reserve insists the inflation surge is mostly the result of the economy recovering as the coronavirus pandemic fades away. Senior Fed officials predict price pressures will ease over the next year and lead to lower inflation.

The MarketWatch inflation tracker will help investors stay up-to date.

Each of the four gauges shows the rise in prices over the past 12 months. They also compare the current increase with the 10-year average for each index.

A little about the four gauges.

The consumer price index measures how much Americans pay directly for a wide variety of goods and services: gas, food, clothes, travel, transportation and so forth. Increases in Social Security and many other benefits are also tied to the CPI.

Read: Consumers are feeling the pinch from higher inflation and they don’t like it

Also: Why aren’t Americans happier about the economy? They are paying higher prices for almost everything

The core CPI strips out food and energy prices and tends to offer a more accurate look at underlying inflation. How come? Food and especially gas prices can swing up and down from time to time and give a distorted view of overall inflation.

The Fed doesn’t ignore food and energy, mind you; the central bank just tries to discount short-term movements.

Take gasoline. The cost of motor fuel sank by a 34% yearly rate at the onset of the pandemic in the spring of 2020. Fast forward to May, and the cost of gasoline had surged at a 56% pace over the past 12 months.

If gas or food prices rise sharply over time, the increases will eventually show up in the main consumer price index. But that’s often not the case.

The other set of inflation barometers MarketWatch is tracking are the PCE and core PCE. Otherwise known as the personal consumption expenditures index.

The PCE is the Fed’s preferred inflation barometer. It puts more weight on medical expenses and tracks both direct and indirect costs borne by consumers.

It also takes into account changes in what Americans buy. Let’s say the price of beef rises sharply and shoppers switch to a cheaper protein such as chicken or pork. These substitutions tend to result in lower inflation.

Read: The CPI-vs.-PCE debate and other ‘rabbit holes’ to avoid on inflation

Over time the PCE inflation gauge runs cooler than the consumer price index. Yet even the PCE right now is unusually high.

The 12-month rate rose in April to a 13-year high of 3.6% and is expected to climb even higher in May. The next PCE report comes out in two weeks.