This post was originally published on this site

Investors weighing stocks as a way to beat inflation may want to look beyond the U.S. market, according to research from Citigroup.

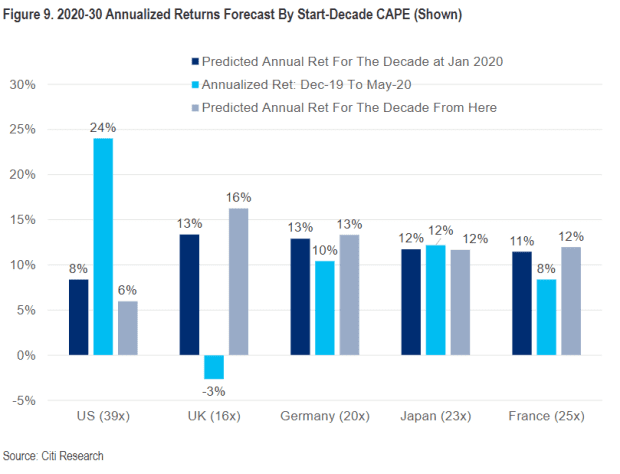

While equity gains exceeded inflation in decades outside the 1970s and 2000s, valuations matter more to long-term performance, Citi strategists said in a research note Monday. Based on cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings, or CAPE ratios, they predicted U.S. stock returns will lag annualized double-digit gains in the U.K., Germany, Japan and France for the rest of this decade.

The U.S. stock market looks expensive with a CAPE ratio of 39x, setting it up for an annualized return of 6% for the remainder of the 2020s, according to their research. That’s similar to U.S. stock gains produced during the 1970s — a decade marked by high inflation, the report shows.

“But it would take quite some upturn in U.S. inflation to turn this into a negative real return,” the strategists said. Still, they suggested that “maybe the best inflation hedges are to be found in the cheaper markets outside the U.S,” where real stock returns may remain positive “even if inflation rose towards 1970s levels.”

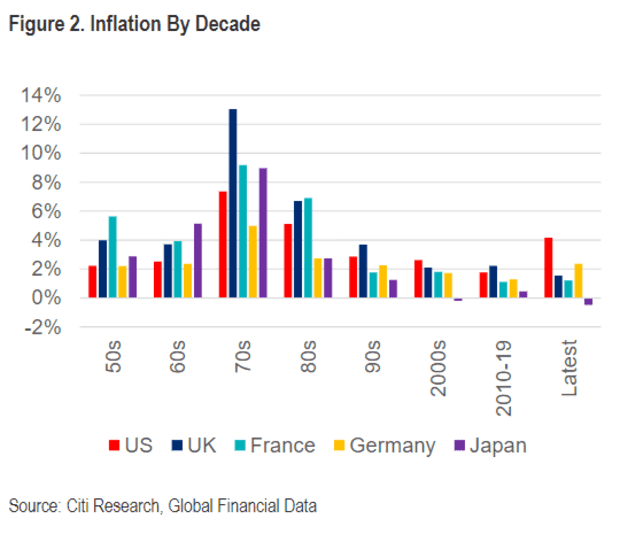

Investors have been watching inflation measures closely, trying to gauge whether a jump in prices will prove temporary, as the Federal Reserve has suggested, as the economy recovers from the pandemic. The U.S. consumer-price index surged to 4.2% in April, the highest level since 2008, while inflation is picking up in most countries.

See: The biggest ‘inflation scare’ in 40 years is coming—what stock-market investors need to know

U.S. inflation will rise to 2.7% this year, slowing to 2.1% in 2022, Citi economists estimate. While “everybody knows that bonds are vulnerable to higher inflation,” the bank’s strategists questioned whether equities can offer a hedge as they have in the past, when commodity stocks stood out for their best real returns.

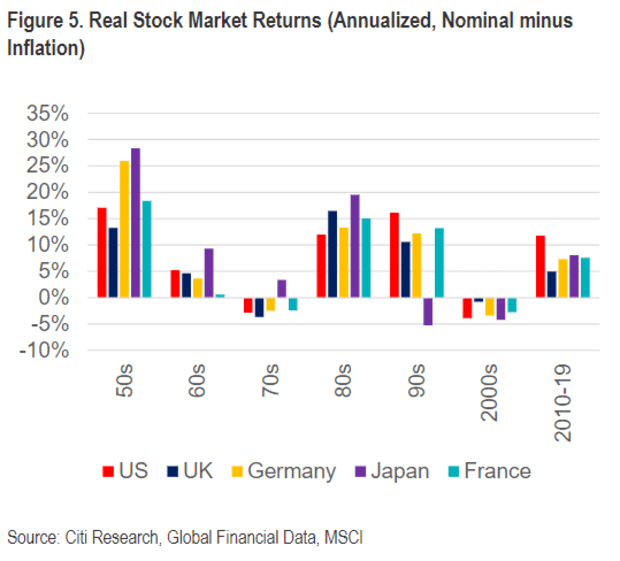

During the 1970s, when investors struggled with 7% inflation, the only sectors that produced “positive real returns” in the U.S, were energy and telecommunications, their research found. “However, the natural inflation-hedging qualities of oil stocks have been constrained by ESG concerns,” the strategists said. “Maybe mining stocks will do a better job this time round.”

In the 1970s, more “rate-sensitive sectors,” such as durables, healthcare and information technology, had some of the weakest annualized returns, according to their report. As for the “negative” real returns for stocks in the 2000s, “it was the combination of high valuation at the start of the decade and financial crisis at the end that proved fatal, despite much lower inflation.”

While “equities have been a decent hedge against inflation” in the past, the Citi report shows that “double digit inflation and interest rates, as seen in the 1970s, were too much to beat.”

Rates today, by contrast, have stayed low “partly because of the ‘we won’t hike even if inflation picks up’ rhetoric from central banks,” the analysts wrote. “Perhaps if real yields stay negative then high equity valuations can be sustained.”

That means the “key issue for equities” is how central banks will respond to rising inflation, the strategists said. They estimated that a rise in real rates to the 1% level “seen at the end of the Fed’s last tightening cycle would imply global equities trading on a PE of 13.5x, with prices 30% below current levels.”

See: ‘Good’ inflation or ‘bad’? Investors are scared because they can’t tell difference just yet

Real rates matter more to the valuation of growth equities than to value stocks, according to the report. “This suggests that the much-predicted bursting of the growth stock bubble won’t happen until real rates rise significantly, something that central banks remain reluctant to let happen,” the strategists said.

The Fed will next week hold its fourth policy meeting of the year.

“In their March forecasts, the Fed projected that, despite clearly achieving all of their long-term economic goals by the end of 2023, they did not foresee any increase in the federal-funds rate before 2024,” said David Kelly, chief global strategist at J.P. Morgan Asset Management, in a note Monday.. “If, after reassessing their forecasts for the economy next week, the Fed maintains this extraordinarily dovish stance, then the risk of a boom-bust recession will have increased to a substantial degree.”

The Dow Jones Industrial Average index

DJIA,

a blue-chip gauge of the U.S. stock market, briefly surpassed its all-time high on Monday before turning south. In midday trading, the S&P 500

SPX,

was slightly lower but not far off a record close set last month, while the technology-laden Nasdaq Composite Index

COMP,

was up modestly.