This post was originally published on this site

China’s policy makers fired a “shot across the bow” of currency markets this week in a bid to slow the rise of its currency. The move might work in the short term, but fundamentals are likely to favor a stronger renminbi over the long run, analysts said.

Last week, China’s currency traded at fewer than 6.40 yuan per dollar, its strongest level since 2018. Over the past year, the renminbi

USDCNY,

USDCNH,

has rallied more than 12% versus the dollar. Although the terms are often used interchangeably, the renminbi is China’s national currency, while the yuan is the unit of account.

After a series of public pronouncements attempting to cool the currency’s rise, the People’s Bank of China took more concrete action on Monday by raising the foreign exchange reserve requirement for banks, effective June 15.

As a result, local banks will be forced to purchase and hold more foreign exchange on their balance sheets, The change in policy should put pressure on the renminbi in the short term and act as a “temporary roadblock for further renminbi strength,” said Brendan McKenna, international economist at Wells Fargo, in a Wednesday note.

Why has the renminbi been so strong? Look at the fundamentals.

COVID-19 cases have been contained, allowing China’s economy to operate at full capacity and for nationwide mobility to return to pre-pandemic levels, McKenna said.

Economic indicators rebounded quicker than China’s emerging-market peers, as well as most developed economies, allowing China to become a “safe haven” within emerging markets and a destination for capital flows from foreign investors, he noted.

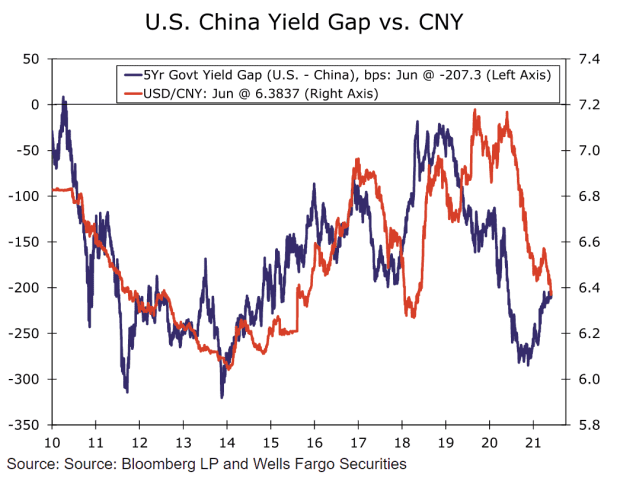

In turn, the renminbi benefited as capital flows picked up, McKenna said. The economic recovery has also boosted yields on China’s sovereign debt, which have risen to pre-pandemic levels and offer positive real, or inflation-adjusted, interest rates. With consumer price inflation in China below 1%, real yields on medium-to-longer-term bonds are around 2.2%, versus negative real interest rates in the U.S.

“In the current low-rate environment, investors are in ‘search for yield’ mode,” McKenna wrote. “With local currency debt in China offering attractive yield dynamics, foreign investors have been quick to deploy capital to Chinese sovereign debt, which has also provided support to the renminbi over the past year.” (See chart below.)

Wells Fargo Securities

But keep the currency’s moves in perspective. Carl Weinberg, chief economist at High Frequency Economics, noted that the currency remains within its official trading band, which is set as a range against a basket of currencies.

While the renminbi has touched the lower end of the range three times in the past five years, it hasn’t even tested the top of the range, and currently sits about two-thirds of the way up, he said in a Tuesday note.

“So the problem for the yuan is not that it is appreciating overall, but rather that the dollar has depreciated about 11% against its trade-weighted basket over the last year,” Weinberg noted. “The yuan is up only 0.8% year-over-year against the euro

EURCNY,

for instance.”

Meanwhile, a stronger currency relative to the dollar has its advantages. It lowers the costs of the commodities and other primary materials denominated in dollars as the economhy reopens, helping offset inflationary pressure on domestic prices from rising prices for petroleum and industrial products, Weinberg said.

The downside is that prices of China’s exports are higher in dollar terms, though investors should keep in mind that the U.S. currently makes up a small portion, perhaps 15%, of China’s exports, Weinberg said.

Weinberg isn’t convinced that official China is all that worked up about a stronger currency versus the dollar.

Analysts at Société Générale saw the decision to raise the FX reserve requirement ratio as a sign of discomfort with renminbi strength. After all, such moves are rare. The last hike came in 2007 when capital inflows were strong and the currency’s appreciation was rapid, they noted, though the impact was expected to be limited.

“Higher FX reserve ratios in China are a warning shot across the FX market’s bows as the yuan appreciates, but the flow of money into Chinese bonds means the pressure isn’t going to go away suddenly,” they wrote.

Wells Fargo’s McKenna saw scope for further action.

“Going forward, it would not surprise us if the PBOC took additional action to disrupt the path of the currency,” he wrote. “These actions could include purchasing U.S. dollars and adding to the PBOC’s FX reserve stockpile, encouraging state banks to purchase U.S. dollars as well as stepping up verbal intervention efforts.”

Weinberg, meanwhile, argued that balance-of-payment issues were likely the main driver of the currency’s strength against the dollar. In particular, the use of the yuan along the Silk Routes for financing infrastructure and transacting trade has boosted its value and will continue to do so.

China has become a global leader in loans to emerging economies, and repaying those loans in yuan increases demand for the currency, while net income from other direct investments abroad is translated into yuan when it’s repatriated, he said.

“As a currency becomes adapted for international uses, it naturally appreciates as demand for it increases,” he wrote.

It’s a process that’s set to continue, Weinberg argued.

“There will be ups and downs along the way, but we believe the yuan is on an unstoppable ascent towards global transaction currency status,” he wrote. “It will rise on all cross rates as its uses in the world increase in volume.”