This post was originally published on this site

Pension obligation bonds are a municipal red flag.

When a state or local government’s liability to its pension system grows beyond what seems manageable, officials are often tempted to issue debt to pay down some or much of that amount. Bonds have fixed interest rates, and they’ve been near long-time lows for the past decade.

In contrast, a pension liability can fluctuate from year to year — and usually just gets bigger as the necessary annual budget contribution gets added to an existing funding hole.

In his 2022 budget address, Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett wrote of his city’s predicament, “We are facing an unsustainable demand driven primarily by the pensions for public safety employees. We must begin preparing now, setting aside money to blunt the impact of the massive payments coming due in just two years.”

For many local governments, making a big deposit all at once and being able to budget for more manageable payments in the future, for both debt service and annual pension payments, can feel like a relief.

But there are many reasons it’s a bad idea, and one that many municipal-finance observers find problematic.

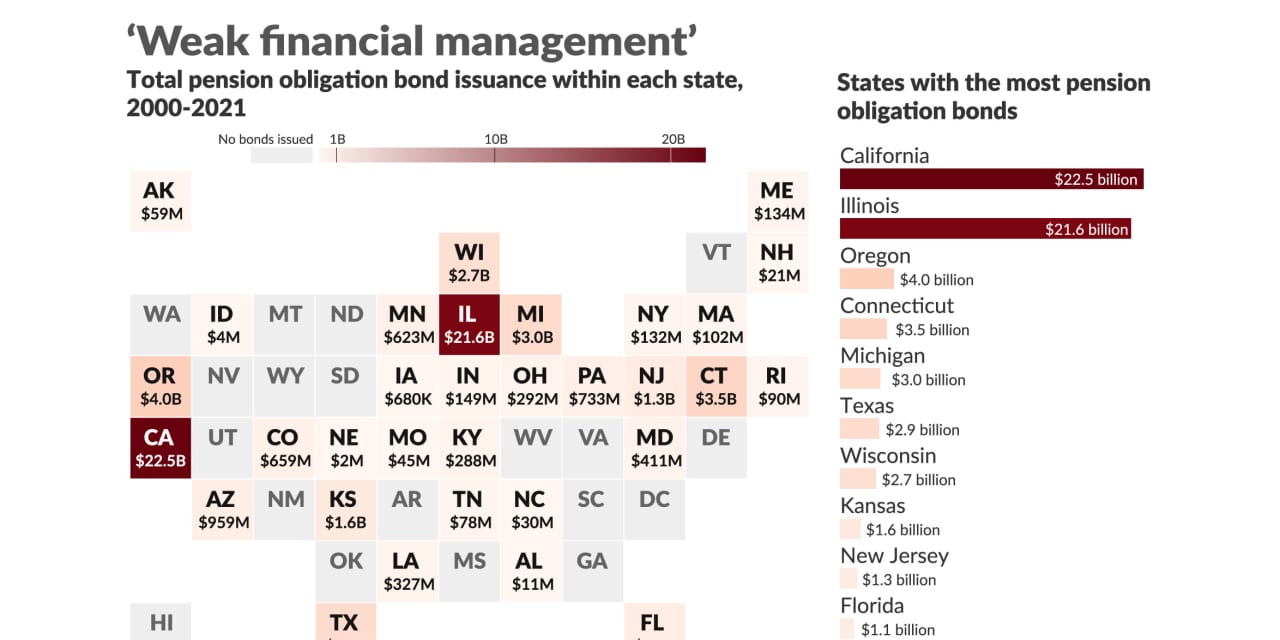

“It’s typically a sign of weak financial government,” said Matt Fabian, a partner with Municipal Market Analytics. MMA compiled all municipal pension obligation bond issues within each state over the past two decades, as noted in the map above.

It’s almost always more financially-strapped governments that issue such bonds, Fabian told MarketWatch, and while those entities always make clear that the bond proceeds will help fund the pension, what’s usually left unsaid is that they will also help the government balance the budget.

That is, the debt may be used to increase a pension’s funded level, bringing it from, say, 50% to 75% funded. But governments will almost always also use the proceeds to skip a year or two of normal budgeted contributions, which usually doesn’t get as much attention, Fabian pointed out.

The Government Finance Officers Association, an industry group for local government financial managers, advises against issuing the debt.

That’s mostly because the bond proceeds, when invested, might perform poorly, leaving the government on the hook for debt service without much to show for it.

Read: Public pensions won’t earn as much from investments in the future. Here’s why that matters

But there are other reasons. Pension obligation bonds are taxable, meaning they often have complexities that most plain-vanilla municipal bonds don’t, the GFOA points out. Among other things, “taxable debt is typically issued without call options or with ‘make-whole’ calls, which can make it more difficult and costly to refund or restructure.”

Finally, increasing any jurisdiction’s bonded debt burden is a serious step to take, the GFOA notes, and something that credit-ratings agencies watch closely. They “may not view the proposed issuance of POBs as credit positive, particularly if the issuance is not part of a more comprehensive plan to address pension funding shortfalls.”

It’s no silver bullet, but slow-and-steady budget efforts are the best way to keep pensions healthy, Fabian said: municipalities that commit to making a “reasonable” contribution, using “standard” assumptions rather than creative accounting, and refusing to cave to political pressure to increase or decrease benefits, will usually be just fine over the long term.

Katie Marriner contributed the map graphic to this article

Read next: In one chart, how U.S. state and local revenues got thumped by the pandemic — and recovered