This post was originally published on this site

Youth may be wasted on the young, but Ken Dychtwald seems to have made the most of his — and the thing is, he hasn’t lost it.

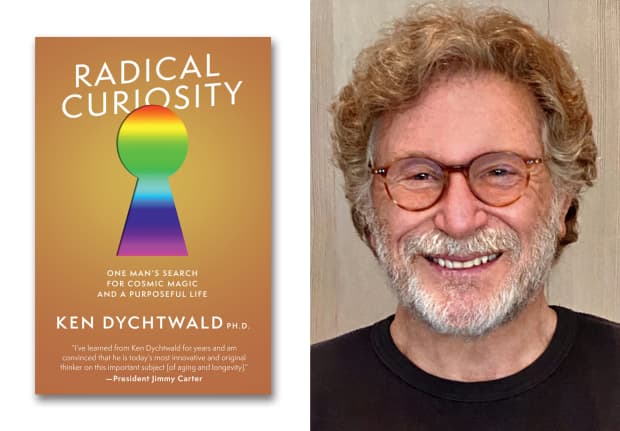

Now a respected gerontologist, author and global influencer of how people think about aging and living in old age, Dychtwald didn’t start out intending to be any of these. As he explains in his newly published memoir, “Radical Curiosity: One Man’s Search for Cosmic Magic and a Purposeful Life,” his younger self would have been perfectly content to practice yoga and teach human potential workshops at The Esalen Institute in Big Sur, Calif.

But life often has a way of making other plans for us, and in his mid-20s Dychtwald found himself in Berkeley, Calif. helping people three times his age improve their emotional and physical well-being. It was the start of a journey where the teacher became a lifelong student who listens, observes and then communicates new ways for old people to see themselves and to be seen, so they might enjoy a late-life renaissance many refer to as “elderhood.”

In this interview, which has been edited for length and clarity, Dychtwald, 71, offers tips about living with ever-increasing amounts of grace, wisdom and perspective, and tells why it’s important to enlist an elder mentor to guide you — at any age.

MarketWatch: “Radical Curiosity” is a memoir of a life that continues to be well-lived, and the book’s subtitle: “One Man’s Search for Cosmic Magic and a Purposeful Life” neatly sums up your journey so far. So tell us, what’s radical about curiosity?

Ken Dychtwald: I’ve lived my life as a seeker. I believe that we, as human beings, have extraordinary potentials and we’re likely only using a tiny portion of them or even trying to access them, whether it be physical or creative or mental or professional or even spiritual. So I believe that part of my job in this life is to continue to turn on more of my burners, to try things that maybe I’m not so good at or explore areas that are new to me or to increase my understanding of my own personal powers. There’s always room for newness and continued personal growth.

Along the way, I’ve always sought out teachers, workshops, therapies, books and ideas that could allow me to advance. Not advance in how much more money I can make, but advance as a human being.

MarketWatch: People in their 30s and 40s especially might not believe there’s room for much beyond family, work, finances and other daily challenges. To them, being a seeker is a luxury for the young and the old, who have more time and fewer obligations.

Dychtwald: One dimension that could be helpful for people in their 20s, 30s or 40s is to seek out mentors. For example, there was an exercise I did when I was 24; I’d come out of four years studying and working at Esalen and had moved to Berkeley to start The Sage Project — America’s first preventative health research project with the elderly. Because what we were doing was so new, one week I asked everybody as a homework assignment to graph their life and to bring in pictures of who they used to be.

We group leaders looked at their pictures, and although it sounds silly, we were struck by how these people weren’t always old. In their photos we saw young, attractive people — who looked a lot like our own friends. The other thing that was compelling was how each of these elders talked about their lives in a very emotional way. In their graphs, there were high peaks and then there were lines that sloped downward for decades.

One of our group members reflected on a marriage that was loveless while another bemoaned a decades long job that her parents wanted her to do but she never enjoyed. One 90-year-old participant loved telling us all about how a career switch in his 40s combined with the arrival of his kids allowed him to feel like he had found his best self and soared.

I thought, I am in the presence of elders who are near the end of their lives looking back, and there are lessons here about the importance of following your heart and working really hard at what matters most to you and leaving aside things that aren’t important.

I learned this at the beginning of my life, and what an important lesson to learn — and how lucky I was to have elders to guide and mentor me. So one thing I say to younger people is that you’re not supposed to know it all. You might benefit from having mentors at work and in life. And you should keep an eye out for new mentors as your life evolves.

MarketWatch: Being a seeker also implies that one is searching, and American culture in particular expects adults to have life pretty much nailed down.

Dychtwald: While that mindset might work for some, I’ve come to appreciate that life is far more fluid than that. I also think that many young people have been influenced by popular self-help gurus who suggest that life is supposed to always be blissful and that every day you’re supposed to be having a grand old time. I don’t feel that way. Sure, I’ve had many blissful moments with my wife and kids and my work, but a lot of times it’s been hard. I’ve had successes that I’ve rejoiced in and I’ve had lots of losses and failures. I always dream high, but I’ve learned that things don’t always meet my expectations and that’s okay.

So the landscape of life isn’t always filled with smiley faces, and that’s okay. You might have to work really hard at something for 30 years for the payout. Not all payouts happen immediately.

In addition, so much in my life happened by serendipity. For example, I really thought I was going to spend my whole life in yoga pants at Esalen and maybe roam the world leading body-mind workshops. Did I think that one day I’d be a gerontology expert and adviser to corporate CEOs and government leaders? It never crossed my mind. Then one morning at around 5:30 a.m. this guy showed up at the front door of my little cabin in the woods — my landlord whom I had never met, a Big Sur crazy — and put a gun to my head and told me I had to get out before sunrise.

I left Big Sur, which bounced me into a field of work — gerontology — that at first I didn’t know if I was a fit for, but ultimately became a gift from the heavens. The lesson here is that sometimes you might be expecting one thing and something else appears in front of you that might turn out to be better.

MarketWatch: So the takeaway is to always be open to the unexpected and where it might lead. That’s good advice for any age, but older people often feel their best days are done — that somehow potential and possibilities are for the young.

Dychtwald: One of the problems with today’s model of aging is that people often say that society renders them irrelevant as they’ve gotten older. There’s definitely pervasive ageism and discrimination and prejudice, but I’d say, equally, people render themselves irrelevant as they get older.

For example, if you want to be able to understand what an African-American 19-year-old girl in college is feeling about college debt, you’ve got to take some time to think about it and feel empathetically what it is to be her. Or if you haven’t ever reflected on what a single dad in his 30s has been going through during COVID, take some time to think about it.

If I want to be a better leader of people or ideas, I can’t just major in myself. I’ve got to become more thoughtful and more expert at understanding others — especially younger people who are growing up in a time and with social forces and technologies utterly different than when we were their age. For example, during COVID, I took on TikTok as one of my hobbies, and my friends would say to me, TikTok? That’s silliness. You know, that’s a bunch of teenagers dancing. However, it’s not what I’ve come to see TikTok as being.

What people are doing can be goofy, but they’re doing production techniques with camera shots and super impositions and fast-forwards and reverse plays that Steven Spielberg didn’t know how to do 20 years ago. Then there’s a million other people doing the same technological marvels a couple of days later. My point is that if I want to be relevant, I just can’t be on my own generational island floating somewhere in the past. If we want to be empathetic and respectful of this new world, we’ve got to take the time and effort to study it and engage in it.

MarketWatch: Flexibility and resilience are key, no matter how old we are. Without it we can be saddled with regrets instead of enjoying and appreciating the moment.

Dychtwald: I don’t think life is a smooth, predictable glide path. I use the example in “Radical Curiosity” of the Apollo 11 mission, which was the most excessively planned scientific experiment in history. Yet 90% of the time the rocket was off-course. The Apollo mission was an exercise in continual course correction, and so is adulthood.

If you think, okay, I’ve planned for retirement. I’ve got my plan, I’ve got my dream house, I’ve got some money in the bank, I’ve got some great friends and now I’m going to glide through it. From decades of research on successful and unsuccessful retirees, I’ve learned that approach may not work out. For example, one of my old friends just learned that her grandchild might have special needs.. Whoa, does that change her retirement scheme. Or I’ve met many people who are simply bored in retirement. Then you’ve got to be willing to pick yourself up and go find some interesting new things to do.

Or maybe your notion of retirement just involves self-indulgence, you know ticking off your bucket-list; what we’ve seen in our studies is that most people are unsatisfied as human beings if all they’re doing is trying to please themselves, and so, taking some time each week to contribute to others becomes an important factor. With so much attention going toward encouraging older folks to be youthful, I think we could all benefit from a little more focus on inspiring them to be useful.

MarketWatch: What would you say to people who feel stuck in their lives and want to break through?

The idea of having an entirely new stage of life in front of you at the end of your work years is not something we studied in college or our parents or grandparents could guide us on, because they didn’t expect it. There are now 1 billion people in the world who are over 60, and it’s as though we’re all pioneers. We’re the first humans in history to reach 60 and look out and say, I might have 20- or 30- or 40 years of life in front of me. What do I make of that? What will I make of myself?

I’m struck by how hard it is to imagine all the different ways you could be in the years to come, and so people struggle because they can’t quite figure out who they could be next. And then, there’s the challenge of teaching an old dog new tricks.

I realize that making new friends, learning a new skill or even reinventing yourself can be a rough exercise. Maybe you have to reinvent yourself because the love of your life has passed away or because you’ve lost your job and you wanted to keep working, or you retire and find that you’re not cut out for a life of leisure. Reinventing oneself in maturity is an exercise that deserves more attention, more guidance.

I’ve come to see that some of us become elderly and some become elders, and I realize it’s only a difference of a letter or two, and I may be playing with words, but the idea of becoming an elder, of becoming a grownup with wisdom and perspective and the potential to be a mentor and maybe even step forward as society’s futurist and guide, is a very exciting proposition. Don’t you think?

More from Ken Dychtwald: What scares me about getting old