This post was originally published on this site

A key artery of global financial markets may be telling the Federal Reserve that enough is enough.

Demand for an overnight funding through the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s overnight reverse repo program (RRP) has begun to flirt with recent records highs, after almost no one used it for months.

Daily repo usage jumped to $394.94 billion on Monday after topping $369 billion on Friday, its highest level since the end of June 2017, according to Tradeweb data.

The Fed’s reverse repo program lets eligible firms, like banks and money-market mutual-funds, park large amounts of cash overnight at the Fed in exchange for a small return, which lately has fallen to about 0.06%.

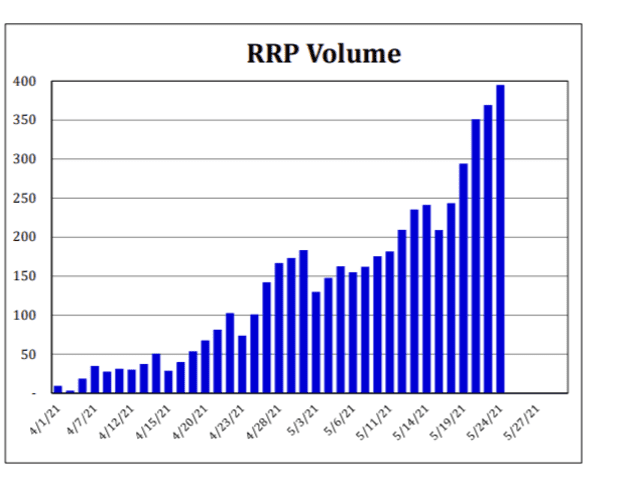

The program had almost no customers in early April, and few since the pandemic’s onset last spring, but daily demand in recent weeks has shot up dramatically. This chart shows the spike in reverse repo demand since April 1.

Spike in reverse repo demand

Curvature Securities

“Why are they going to the Fed?” asked Scott Skyrm, executive vice president in fixed income and repo at Curvature Securities, of firms wanting reverse repo funding, despite its dwindling returns.

“Either there is too much cash or not enough collateral,” he told MarketWatch. “It’s two sides of the same coin.”

It’s also pretty much the opposite of what happened in September 2019, when repo rates suddenly skyrocketed, resulting in the Fed jumping in with a slate of short-term emergency lending facilities that helped calm fears that financial markets might otherwise freeze up.

This time, Skyrm views high demand for the Fed’s low-return reverse repo facility as a sign that the central bank’s roughly year-old $120 billion-a-month bond-buying program no longer works as intended by adding liquidity to financial markets, and should be scaled back.

“Right now, the more money you put in, you get it right back,” he said. “The market is saying ‘It’s time.’ There is the evidence that QE has gone too far.”

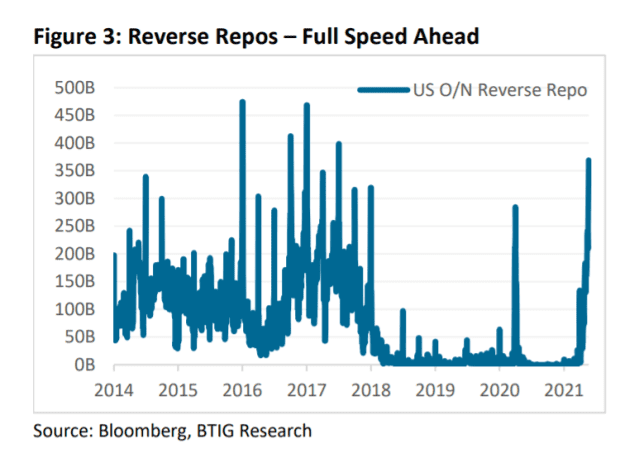

This chart shows the recent spike in reverse repos at the Fed as nearing peak levels of the past decade.

Demand for reverse repos nears peak levels

BTIG

The Fed, under Chairman Jerome Powell, has purchased $2.5 trillion in bonds since the pandemic broke out last year, through its monthly purchases of U.S. Treasurys

TMUBMUSD10Y,

and agency mortgage bonds, or “quantitative easing” (QE).

“This adds liquidity to the system. As the Fed buys bonds, those sellers receive the liquidity and likely buy other bonds, or other product,” Padhraic Garvey, ING’s global head of debt and rates strategy, wrote in a client note Monday.

“The thing is, the liquidity is being placed here as there is nowhere else for it to go to,” Garvey wrote of the Fed’s reverse repo program. “And it’s not really where you want to park cash, given that the rate paid to the cash lender is 0%.”

Overnight reverse repo rates have been sinking to the low end of the Fed’s target policy rates, currently in the zero to 0.25% range.

As MarketWatch reported in April, the worry is that the U.S. central bank could be on the brink of losing control of its benchmark policy rates, without making other tweaks to stabilize rates.

Read: Here’s why a flood of cash could be creating a conundrum for the Fed

Meanwhile, Powell has promised “great transparency” around the Fed’s eventual exit of easy monetary policies. Several Fed officials recently called for the central bank to start discussing a slowdown of its bond purchases, while the latest minutes of the rate-setting committee meeting showed a willingness to explore the topic in coming meetings.

A BTIG Research team led by Julian Emanuel described the situation like a game of cat and mouse.

High demand for the Fed facility “underscores pressures on the short end of the yield curve as near-term rates probe negative territory after a year-plus of extraordinary accommodative policy,” the team wrote in a Sunday note.

But they also expect the issue to last “until investors are confident enough to shift to longer-duration bonds,” which isn’t expected to happen until markets get more clarity on the Fed’s plans to taper its bond purchases.