This post was originally published on this site

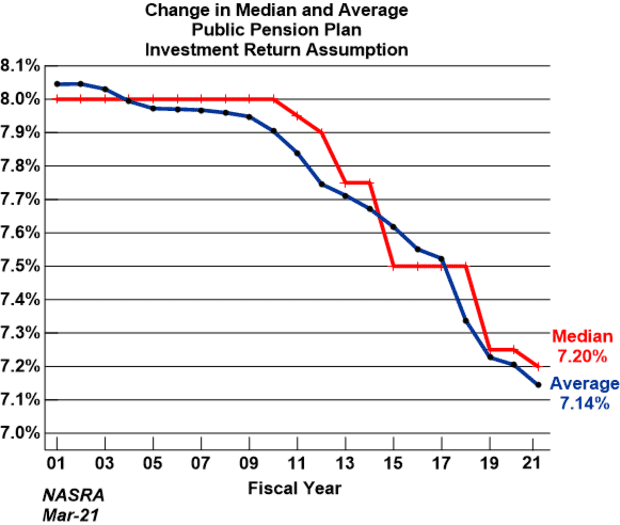

State pension systems dropped the rate of return they assume for their investment portfolios again, continuing a two-decade long trend that public-finance experts say is necessary, even as it presents some challenges for the entities that participate in such plans.

The median assumed return in 2021 is 7.20%, according to a report published early in May by the National Association of State Retirement Administrators, down roughly 1 percentage point since 2000, as the investment managers charged with managing trillions of dollars for municipal retirees have adapted to a more challenging market environment.

Source: NASRA

“Long-term growth projections have come down pretty significantly from the rates of growth we saw going back to the 1990s,” said Greg Mennis, director of the public sector retirement systems project at the Pew Charitable Trusts.

“That’s important because economic growth translates into corporate profits, which translates into asset returns. Having the most accurate possible rate of return means your liabilities are being calculated correctly and reduces the risk you’re setting the bar too high,” Mennis said.

Public pension administrators must figure out how much their plans will need to pay out for every retiree that comes through the system, for decades into the future — and how they will reach that number, using contributions from current employees and employers, as well as investment returns.

All else equal, if a pension system is assumed to earn less from investing, that means it must take in more from municipal employees and employers. Every year, pension system actuaries calculate that amount and translate it into the “bill they send to the city,” as Mennis calls it.

Related: With lower returns on the horizon, public pensions will turn to riskier assets, Moody’s says

In 2019, for example, the city of Milwaukee lowered its assumed rate of return to 7.50% from 8.24%. In a research report from credit-ratings firm Standard & Poor’s, analysts wrote that that step brought Milwaukee’s net pension liability to $1.1 billion, from $303 million.

Even so, “we still consider the lowered (rate of return) as being fairly aggressive, above our 6% guideline, which we believe can lead to heightened market risk, causing contribution volatility,” S&P analysts wrote.

In 2010, Milwaukee’s annual payment due to the pension system was $49 million, Mayor Tom Barrett wrote in his 2021 budget address. This year, the budget calls for a $71 million contribution, swelling to perhaps as much as $160 million by 2023.

Returns, compounded over years, wind up paying for roughly 2/3 of the benefits that must be paid out, Mennis said. It’s important to note that there are years when pension systems won’t meet even the reduced bogey — and years when markets roar higher, as they’ve done over the past 12 months

SPX,

when they’ll top even optimistic expectations.

Most public-finance observers believe that what’s most important is that state and local entities have solid plans in place and stick to them, Mennis said in an interview. Some municipalities have avoided the kind of sticker shock facing Milwaukee by gradually ramping up contributions over time.

In contrast, some of the poster children for poor pension management, like New Jersey, ran into trouble when they allowed themselves to skip annual payments starting in the late 1990s. Now, the state plan is less than 40% funded, and some early budget figures suggest making the full payment deemed necessary by actuaries will take up 15% of the state budget.

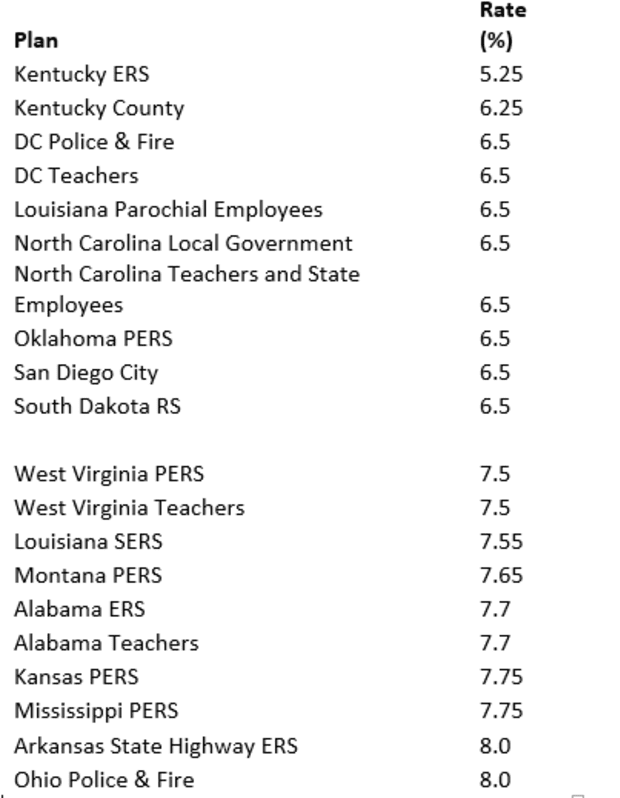

The full list of a few hundred systems’ investment return assumptions tabulated by NASRA is here. The 10 plans with the smallest return assumptions and the largest are noted in the table below.