This post was originally published on this site

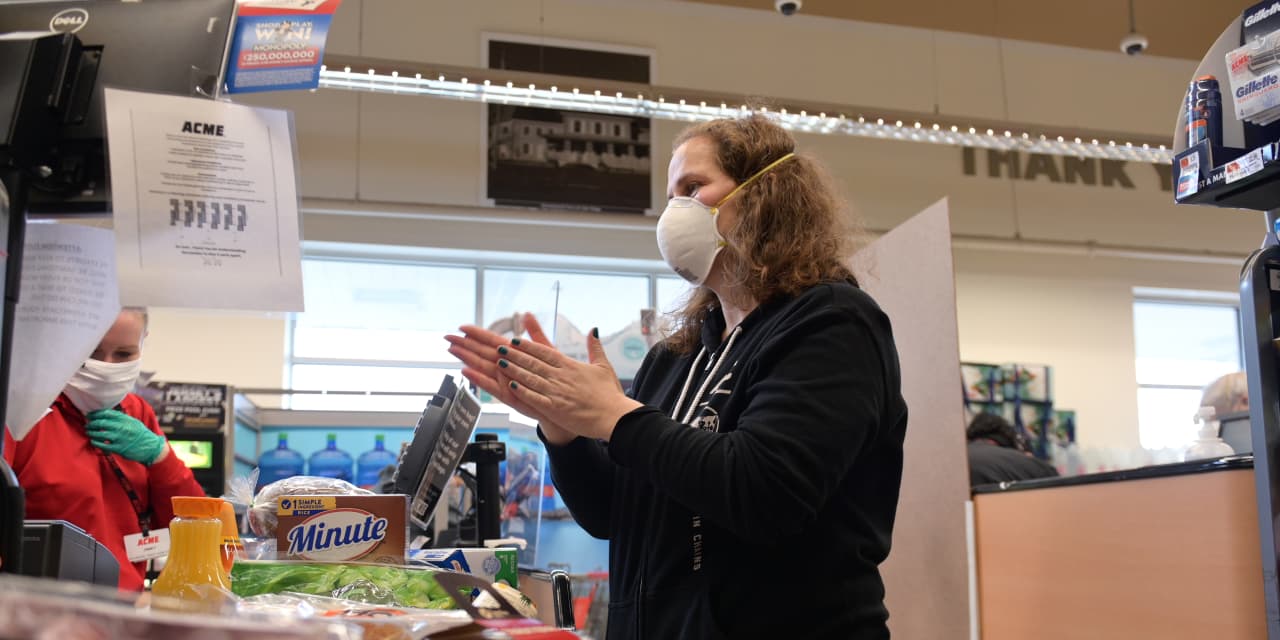

A dollar doesn’t go as far as it used to — and if you don’t believe it, go to a supermarket.

Food prices have been nibbling into household budgets and fattening grocery bills since COVID-19’s emergence, figures show.

After stockpiling shoppers cleaned out stores in early Spring 2020, the ensuing price increases are another display of the global pandemic’s far-reaching warp on supply and demand, according to experts.

The numbers tell the tale.

The average monthly costs of groceries in March increased 3.3% from March 2020, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In every month since April 2020, the price increase has roughly ranged between 3% and 5% from the same point one year earlier.

Throughout 2019 and early 2020, the percentage increase was around 1%, the numbers show.

Likewise, the average price of all grocery store food purchases increased 5.7% from the same period in late April 2020, according to data from NielsenIQ, a market research business.

For example, the “average unit price” for meat (which could group items together like a sirloin steak with chicken drumsticks) was $4.06. That’s an 8.6% increase from the same point last year, the statistics said.

“There’s no question,” said Phil Lempert, a food industry expert who founded SupermarketGuru.com, “I’m spending more on food.” He’s not alone.

The pandemic effect

COVID-19 has put new snags and costs into a supply chain in bad need of fixes, he explained.

For example, worker shortages and social distancing rules push up labor costs in the meatpacking industry, he said. Rising gas prices make trucking a more expensive endeavor, and the logistics are further complicated by more retiring truckers, Lempert noted. Meanwhile, Chinese demands for corn and soybeans drive up those prices, he said.

It’s also layered on new customer expectations about shopping during a pandemic, and all those plexiglass dividers, hand-sanitizer stations and cleaning supplies to wipe down scanning equipment and carts cost money.

“Somebody’s got to pay for it,” Lempert said.

To be sure, there are supply-chain challenges and added costs to surmount those challenges, said Greg Portell, lead partner in the global consumer practice at Kearney, a strategy and management consulting firm.

Food manufacturers are all in the same boat. “That makes it easier for these companies to push it through to consumers,” Lempert added.

The stimulus effect

But there’s also the demand side, he said, boosted by government spending for measures like stimulus checks. “You’ve got actual dollars going into people’s pockets,” Portell noted.

Jim Dudlicek, director of communications and external affairs for the National Grocers Association, a trade association, said food prices have climbed for a number of reasons, including gas costs, consumer demand and “supply chain pressures.”

Still, he added, “As costs rise from producers and the supply chain, our members are following the same pricing structures and policies that they always have, and strive to hold off on increasing prices as long as possible.”

2020 was actually a strong year grocery stores, seeing that so many people stayed home and devoted more of their food budget to eating at home instead of going to restaurants. Last year’s sales were “unprecedented,” according to Bank of America

BAC,

analysts.

But as restaurants feed more people eager to get out of the house as vaccination rates rise, grocery stores face a new set of challenges in keeping customers.

Will prices stay high?

“The next 12 to 18 months are going be wild west,” said Lempert, “because we don’t know what the future holds.” For example, grocery stores, supermarkets and suppliers need to figure out how they can entice shoppers with promotions — but that takes months of planning and certainty, Lempert noted.

Increasing prices are not the new normal, in Lempert’s view. Prices should go down after suppliers along the food industry invest in better, more certain ways to get food on the shelves, he said.

Jared Bernstein and Ernie Tedeschi, members of President Joe Biden’s Council of Economic Advisors, wrote in April that, across the board, they expected “measured inflation to increase somewhat” over the next several months.

They cited “supply chain disruptions, and pent-up demand, especially for services. We expect these three factors will likely be transitory, and that their impact should fade over time as the economy recovers from the pandemic.”

For now though, price increases may hurt families still reeling from the pandemic.

Just over 8% of households said they sometimes or often did not have enough to eat in the past week, according to data collected in mid- to late-April for a running Census survey. In January, 11% of households said they were experiencing that same type of food scarcity.

Late last week, the Biden administration announced it was expanding a program that feeds schoolchildren over the summer. The expansion could feed as many as 34 million children, according to the Associated Press.

The funding comes from money earmarked for food assistance in March’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan. The rescue package devotes $12 billion for anti-hunger programs, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.