This post was originally published on this site

President Joe Biden plans to propose doubling the tax wealthy people pay on their capital gains.

Under the plan, which he intends to present during a speech on Wednesday to a joint session of Congress, the tax rate on profits from the sale of an asset such as property or a stock would go from 20% to 39.6% for those with income over $1 million a year.

Read: Some lower-tax states won big in the 2020 Census count. Are Americans moving to escape the taxman?

Biden also reportedly aims to close a loophole that allows people to avoid paying the capital-gains tax on inherited wealth, which, when combined with the higher tax rate, could raise an estimated $113 billion over a decade. Biden wants to use the extra revenue to pay for new social programs like paid family leave and free community college.

As a tax-policy expert, I have been following the debate on taxing capital gains and high-income earners for several years.

To understand the implications of raising the tax rate, let’s review some of the basics.

From Peter Morici: It’s time to toss the unwieldy income tax and replace it with something far simpler

What makes a capital gain?

A person’s income in a given year includes anything that can increase their overall net worth — the difference between the value of everything they own minus any debts they have.

A familiar example is your paycheck, which is known as “labor income.” When you get paid for doing a job, your labor income increases your net worth — that is, until you spend it.

But income doesn’t always come in the form of cash. When the value of something you own increases — such as a stock, your home or your 401(k) — this kind of income is known as a capital gain. For example, if you buy some shares in a company for $1,000 and their value appreciates to $2,000, the $1,000 difference is an “unrealized” capital gain — that is, it hasn’t been sold for a profit yet.

While most Americans get the vast majority of their income from wages and salaries, the rich tend to get a large portion of their income from capital gains. For the very highest earners among the top 0.01%, capital income makes up about two-thirds of total income.

How are capital gains taxed?

Unlike wages, capital gains are harder to calculate, and harder to tax.

To tax something, the Internal Revenue Service needs to know its value. But while some assets such as stocks and mutual funds are bought and sold often and so their market price is well-known, others like real estate or fine art don’t change hands that often. That means it’s harder to know their value.

Congress’s solution has been to tax capital gains only when they are realized — that is, when the asset is sold. The gain is the difference between the sale price and the original purchase price, or “basis.”

Fortunately for most people, the largest capital gains they will ever earn — gains on the sale of their home — are usually exempt from taxes, as are capital gains earned in tax-sheltered retirement or education savings accounts like 401(k)s and 529 plans. Three-quarters of all U.S. stocks are held in nontaxable accounts.

As for taxable investments, as long as you hold on to them, you don’t have to pay capital-gains taxes. In fact, if you die, your heirs don’t have to pay, either. Under current law, when someone inherits an asset, its value gets reset. This is known as the “basis step-up.”

Put simply, the basis is the original price you paid for the asset. Let’s say you invested $100,000 in some stock and held on to it until you died, at which point it is worth $300,000. If your heirs eventually sell the stock for $700,000, their basis wouldn’t be $100,000 but $300,000, meaning they would pay taxes on only $400,000 in capital gains. But no one will ever pay tax on the $200,000 in appreciation that accrued before you died.

Biden’s plan would eliminate this basis step-up and require heirs with incomes over $1 million to pay taxes on the entire amount of their capital gains.

What’s the current tax rate?

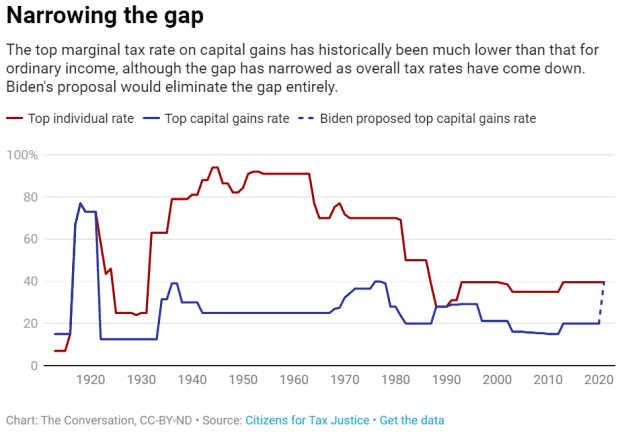

When the modern income tax was created in 1913, capital gains were taxed at the same rates as ordinary income — as high as 77% in 1918, the year World War I ended.

After the war, conservatives began to make the case for tax cuts. So Congress lowered the top individual tax rate to 58% in 1922 and split off capital gains from regular income, slashing the rate to 12.5%.

Since then, capital-gains rates have been changed frequently, climbing as high as 40% but typically remaining much lower than the top rate on ordinary income. The capital-gain-tax rate is currently 20% on incomes over $441,450 and 15% on incomes from $40,001 to $441,450. There’s no capital-gains tax on income of $40,000 or less.

It also depends on how long you own the asset. If you buy and sell in less than a year, it’s considered a short-term capital gain and is taxed at the same rate as your wage income.

What’s the impact of the capital-gains tax?

Supporters of relatively low rates for capital gains argue that this stimulates entrepreneurship, mitigates double taxation of corporate income and alleviates the “lock-in” effect that discourages investors from selling assets to avoid taxes.

They also point out that inflation erodes the real value of capital gains. Lower rates help offset this penalty.

Other research, however, suggests that cutting capital-gains taxes has no significant effect on economic growth and creates other distortions that hurt economic efficiency. For example, hedge-fund managers exploit the “carried interest” loophole to categorize their income as capital gains instead of wages so they qualify for a lower tax rate.

Whether or not capital-gains-tax policy actually increases economic efficiency, tax scholars do know it makes the tax system more regressive. Since capital gains are highly concentrated among high-income taxpayers, tax breaks for capital gains primarily benefit the wealthy.

The Tax Policy Center estimates that in 2019 taxpayers with incomes over $1 million received over three-quarters of the benefits of lower rates, while taxpayers earning less than $75,000 received only 1.2%.

Stephanie Leiser is a lecturer at the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan.