This post was originally published on this site

The passage of time guarantees that Berkshire Hathaway will one day be without the man synonymous with creating one of the world’s most valuable and admired businesses.

While ground-level management of Berkshire Hathaway’s BRK.A BRK.B decentralized individual business units will continue unchanged, filling Warren Buffett’s shoes will require some changes.

The most important role to fill will be CEO, one of three jobs now held by Buffett (he is also chairman and chief investment officer). While the actual name remains a secret, the background and skillset of Greg Abel suggests the board will choose him.

The primary reason is Abel’s extensive experience with capital allocation. During his time running Berkshire Hathaway Energy, and later as vice chairman overseeing non-insurance operations, Abel oversaw many acquisitions. He is also much more comfortable in the spotlight and about 10 years younger than Ajit Jain, the vice chairman in charge of insurance operations, which would give him a longer run at the helm. Jain, by contrast, is a brilliant handicapper more comfortable evaluating insurance risks (though he is also one of the best executives in the world, having overseen acquisitions of his own).

The role of chairman will likely fall to Buffett’s son, Howard, whose primary duty will be to ensure Berkshire’s culture remains intact. Responsibility for managing Berkshire’s investment portfolio should fall to Todd Combs and Ted Weschler, who joined Berkshire in 2010 and 2011, respectively.

Integral to the C-suite changes is the important question regarding Berkshire’s future capital allocation.

Berkshire’s earning power all but guarantees it will have enough cash to invest in worthwhile projects at the subsidiary level and ample cash to make opportunistic acquisitions. That means cash will need to be returned to shareholders.

Here Berkshire has two main options and a blended third.

The quickest way to return capital to shareholders is via dividends. But dividends are tax-inefficient and impose a single standard on all shareholders, two reasons why Buffett has resisted paying one in the past. A better way is through share repurchases which, assuming they are made at prices below intrinsic value, instantly increase per-share value for remaining shareholders. However, share repurchases are price-dependent.

“

The next generation of Berkshire’s leaders are likely to hear loud calls from Wall Street (and perhaps some shareholders) to break up Buffett’s life’s work

”

This leaves a blended option as the most logical course of action. Berkshire could set a regular dividend equal to, say, 25% of normalized operating earnings. Then if share repurchases aren’t available or an acquisition doesn’t materialize, infrequent special dividends could be declared.

A dividend during Buffett’s remaining tenure is unlikely if share repurchases remain an option. But the day will come, perhaps soon, when Berkshire simply cannot allocate all the capital it generates and will need to pay a dividend. Longtime shareholders will recognize the need for such a change in policy, and others will rejoice at the prospect of Berkshire as a dividend-paying stock.

What the company’s new leaders are unlikely to do is break up Berkshire Hathaway. More so than other conglomerates, this firm is truly more than the sum of its parts. The conglomerate gains in tax efficiency, diversification, and capital allocation. Dismantling Berkshire to “unlock” value via higher price-earnings multiples would destroy these advantages and incur unnecessary taxes. Most important, it would tarnish the reputation Berkshire has carefully nurtured as a permanent home for generational family businesses.

Buffett put it succinctly in his 2018 Chairman’s letter, published in 2019: “Truly good businesses are exceptionally hard to find. Selling any you are lucky enough to own makes no sense at all.”

Yet the next generation of Berkshire’s leaders are likely to hear loud calls from Wall Street (and perhaps some shareholders) to break up Buffett’s life’s work. The crux of the argument over breaking up Berkshire comes down to what constitutes value.

Harriman House

Berkshire was built on the notion that value – the sum of all future cash flows discounted to the present – is independent of the stock market’s appraisal of that value. The underlying cash flows of Berkshire’s many subsidiaries would not change upon being separated into pieces (in fact they could be lower considering duplicated costs), which means that their value would not increase after a breakup. The subsidiaries already take advantage of opportunities for organic investment and bolt-on acquisitions that come their way, and Berkshire has taken care of the reinvestment problem by allowing excess cash to be sent to headquarters.

Instead, Berkshire’s future value creation will likely come by minimizing the downside (maintaining insurance underwriting discipline and resisting mediocre capital allocation moves) to allow infrequent but meaningful advantages to accrue and accumulate to the benefit of ongoing shareholders.

Value can be created by time arbitrage (a long-term business owner in an often short-term-thinking market), being a permanent home for family businesses (private-market discounts), by acting as an alternative source of financing when credit markets dry up (as Buffett did in the financial crisis when he invested $14.5 billion over the course of three days in Goldman Sachs, Wrigley, and General Electric), and through opportunistic share repurchases.

Of course, the ultimate fate of Berkshire Hathaway rests with its shareholders. Berkshire will undoubtedly not look the same in 25, 50 or 100 years, but it should thrive without Warren Buffett because of the unique corporate culture that he and Charlie Munger so painstakingly nurtured for the last half-century.

That is perhaps the highest praise one can give a man who took a blank canvas and turned it into one of the finest and most highly valued pieces of artwork the business world has ever seen.

Also: Warren Buffett’s latest advice could help you retire much richer

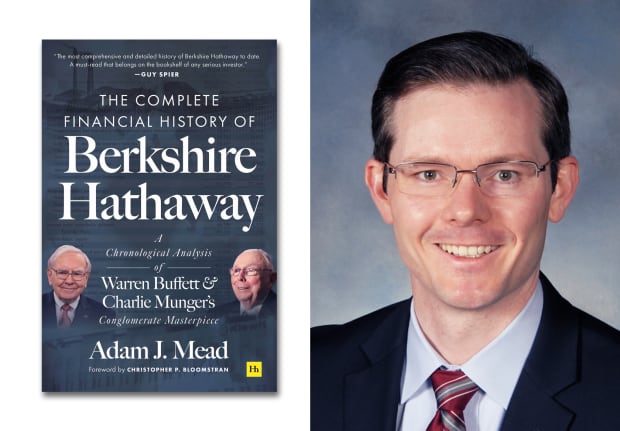

Adam J. Mead is CEO and chief investment officer of Mead Capital Management and founder of Watchlist Investing. Follow him on Twitter @BRK_Student. This is adapted from “The Complete Financial History of Berkshire Hathaway: A Chronological Financial Analysis of Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger’s Conglomerate Masterpiece.”