This post was originally published on this site

The last time I interviewed Ken Dychtwald, psychologist, gerontologist and founder and chief executive of Age Wave, a consulting and research company, he said: “When some people retire, they struggle with their identity, relationships and activity. Many feel unsettled, anxious or even bored, but eventually they realize that relationships, wellness and purpose really matter — perhaps more than ever.”

Ken Dychtwald is now 71 and is not retiring, but he has already realized what really matters. And that’s the spine of his new book, his 18th, “Radical Curiosity: One Man’s Search for Cosmic Magic and a Purposeful Life.”

His book is personal. It’s gritty and wise. It’s a jumble of human foibles and shiny successes. It’s about loss and love and pride and the weaving together of a wild adventure of a life. And it’s about the importance of extracting lessons from a life fully lived.

I’ve known and admired Dychtwald for many years, sought his counsel, laughed with him, and sat alongside him at star-powered events, as he and his wife, Maddy, worked to raise awareness for Alzheimer’s via nonprofits UsAgainstAlzheimer’s and the BrightFocus Foundation.

For more than 40 years, he has dedicated his career “to investigating how people, especially boomers, relate to becoming elders,” he writes at the start of his book. And “it turns out I have become an elder myself.”

I spoke with Dychtwald recently about the book, and all kinds of other things. Some highlights of our conversation are below and have been edited and condensed.

I also recommend taking the time to check-out this terrific video from his official book launch filmed at Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California.

Kerry Hannon: What scares you the most about growing old?

Ken Dychtwald: Being in gerontology now for 45 plus years, I’ve seen a lot of suffering. We’ve done a reasonably good job of causing people to live longer lives, but we’ve done a questionable job of causing our health spans to that match our lifespans. Watching my mom, for example, spend 12 years being decimated by Alzheimer’s was terrifying. Watching my dad go blind and mad from the combination of losing his vision — and his sanity — due to macular degeneration and the struggles of his beloved wife was unnerving. Achieving longevity without health can be a hurting proposition.

What also scares me is that I’ve seen a lot of older people either be rendered irrelevant or render themselves as irrelevant. The idea that I somehow get sent off to senior playpen is unacceptable to me.

What do people get wrong about aging?

I think we should primarily seek to be useful, not just youthful, and not only useful, like let me watch the grandkids — but to do something helpful, even important in my elder years. We need a whole new framing of the value and purpose of longevity. As odd as it sounds, I think elders should be society’s futurists

What does radical curiosity mean to you?

Vitality and open-mindedness comes from curiosity. Radical curiosity comes from being inquisitive. It comes from continually wanting to learn, to reach out from your own viewpoint, cohort or neighborhood and better understand others. Radical curiosity is to be curious about life and death, to be curious about the rise of women in this incredible new era, to be curious about relationships within the younger generations, to be empathic about the potentials and plights of people who may have a different racial or ethnic background than you.

You don’t hear curiosity talked about much. There’s a bit too much of “all the answers can be found on Google.” We need to raise kids to be curious.

Read: A revolutionary ‘gray army’ of older workers is fighting our youth-obsessed culture

You write that we shouldn’t wait until we’re old to learn how to live our life on purpose? Can you explain?

I have worked a lot with elders over the years. And people would say, ‘I spent decades not doing what I wanted,’ or ‘I could have been a more important figure in my community’ or ‘I wish I would have taken more risks and tried what I was really dreaming of.’

In fact, I think that high school kids ought to take a course taught by elders on how to live a purposeful life because many of them taught me that they felt they had not — and were living their final days with many regrets.

From working with elders I also realized that I don’t want to be fraught with regrets when I’m 90, or on my death bed. I want to be able to say that I engaged my relationships, my marriage, my being a dad, my work and my role in the community with an intensity. And I also got ahead of my skis a few times and came back from failures. I’ve attempted to both live a life with purpose and do it purposely.

Can you share with me the lesson you learned from the Terminator?

A group of us were brought together to speak at a conference at Harvard in 1977 on the mind and body. There was a private salon dinner the night before at the home of one of the speakers. Arnold Schwarzenegger walked in as a special guest. He was Mr. Universe -fresh from his starring role in “Pumping Iron” and bursting out of his clothes.

After a lengthy discussion about the “powers of mind,” I said to him, so what are you going to do next? And he said I’m going to become the biggest movie star in the world. We all just laughed because he was not an actor and you couldn’t even understand his Austrian accent. He was a big, charismatic muscle guy. And I said, Oh, really, great, good luck. And then what are you going to do after that? And he said, I’m going to get into politics. Maybe I’ll become the governor of California. I’m not making this up. We all rolled our eyes.

I watched him over the next 25 years become the biggest movie star in the world, get into politics, marry into the Kennedys, and then become the governor of California. What’s the point I want to make? I learned from him that there is value in intention matched with discipline. If you want to be fit, put a plan in place. If you want to write a book, don’t just speculate about it. You can even get some help, but get it done. If you want to be a kinder person, maybe you could use some psychotherapy, or your faith leader would work with you.

Who is the most impressive person you ever met?

I’ve had the good fortune of meeting lots of gurus. I knew Tim Leary. I knew Ram Dass. I met Alan Watts. I knew Werner Erhard when he was still Joe Rosenberg.

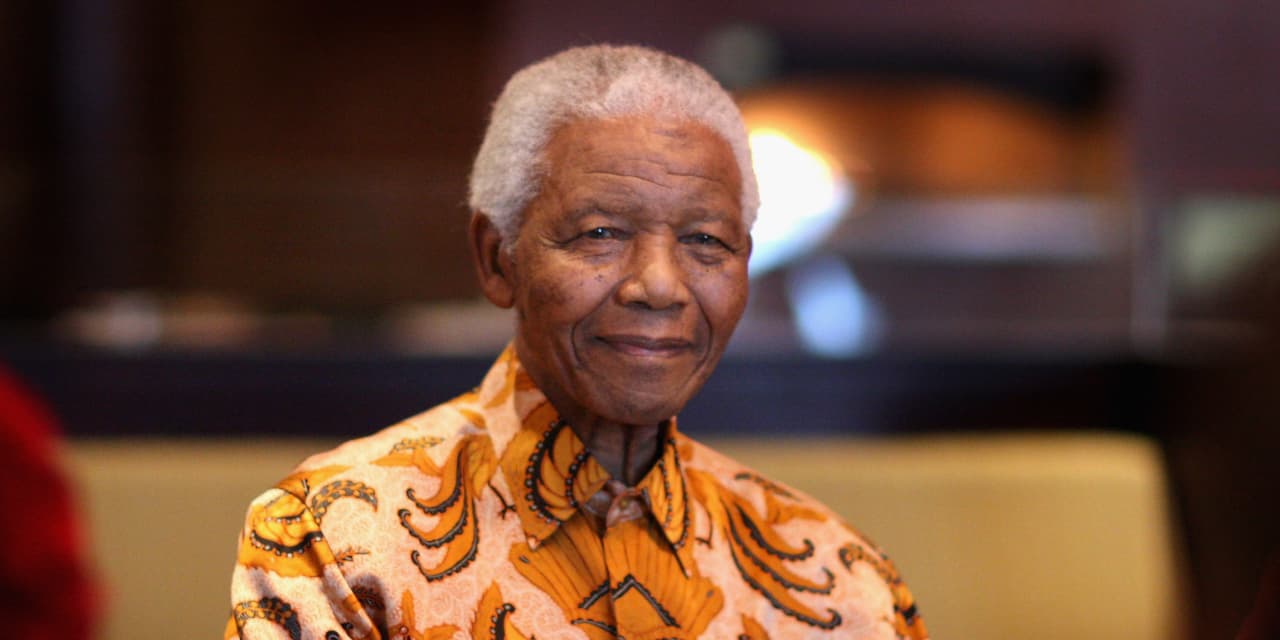

But the most extraordinary human being I’ve ever encountered without question was Nelson Mandela. It was in Davos, and he was speaking to the World Economic Forum, of which I was a fellow. This 80-year-old man comes on the stage, and he was not an old man. He was an elder.

He was erect. He was handsome. He was beautiful. And you’re thinking this guy spent 27 years in prison fighting for what he believed, which was the end of apartheid. This man spent a third of those years in solitary. And here he is with a beautiful, welcoming smile and a humble nature.

Nelson Mandela was respectful and modest. He was grateful to be asked to speak at this meeting, but you also got the feeling that if he wanted to, he could break anyone in half if he wished to. He was modest, but so powerful.

We don’t have many role models as we age. When you get to be 60 or 70, there aren’t a whole lot of role models. And some of them are not impressive. You know some of them are self-indulgent or they’re out of touch. Nelson Mandela was a truly impressive human being — a powerful role model for what an elder can be.

How did Mandela change you?

As an aging man, I’m always wondering who I could be next. And I think that when I encountered Nelson Mandela, which was 23 years ago, I got an impression about an elder that was not about retirement or getting senior discounts or early bird specials. He was a man that had grown more wise, more humble, but more powerful with each year. And I thought that’s an aspirational role model for me.

What is your key takeaway for readers of ‘Radical Curiosity?’

Two things: I think there’s value for all of us over the age of 50 to take some time to gather our stories. We should have a traditional material will with things you own and how you want them distributed when you’re gone, but also an ethical will, your stories, your life lessons — which may be even more important, in the long term.

Even if you only have 10 pages to write, or if you want to dictate it through stories like I did, and then turn it into a manuscript. I think there’s value as we grow older in gathering our stories and our lessons. There’s a phrase in Africa “when an elder dies, it’s like a library burning down.” And I would say when an elder passes without having gathered their lessons, it’s a loss. The wonderful thing that happens when we age — we get to be an integrated adventure story. Why not assemble your key life lessons for others to benefit both from your mistakes and your successes?

Second, there’s a critical role for us to play in our later years as elders. I think there’s an obligation we have as long-lived men and women to be helpful to younger generations, to help improve the environment, to help create more kindness in our geopolitical system, to be more empathetic to those who are challenged or struggling and to share whatever we’ve learned in our life so that people don’t make the same mistakes and gain from our insights.

Read: At what age should I stop saving for retirement?

Kerry Hannon is an expert and strategist on work and jobs, entrepreneurship, personal finance and retirement. Kerry is the author of more than a dozen books, including Great Pajama Jobs: Your Complete Guide to Working From Home, Never Too Old To Get Rich: The Entrepreneurs Guide To Starting a Business Mid-Life, Great Jobs for Everyone 50+, and Money Confidence. Follow her on Twitter @kerryhannon.