This post was originally published on this site

How much of my retirement portfolio do I really want to gamble on a high-risk, low-profit company that is already valued at over 1,000 times its most recent earnings, plus seven times the peak earnings of its entire industry, and which is controlled and run by a volatile eccentric?

Probably not much, to be honest.

But if I follow conventional wisdom and the “best” financial advice I’d be betting somewhere between 1% and 2% of my money on this stock alone.

That’s how much of our money goes into Elon Musk’s Tesla, Inc.

TSLA,

if we invest in an S&P 500 index

SPX,

fund, supposedly the ‘sensible’ way of diversifying our portfolio and avoiding taking big, risky bets.

Right now if you hold an S&P 500 or similar stock market index fund you’ve got more money invested in Tesla than you do in, say, Ralph Lauren

RL,

Molson Coors

TAP,

Gap

GPS,

Hasbro

HAS,

American Airlines

AAL,

United Airlines

UAL,

Delta Air Lines

DAL,

Campbell Soup

CPB,

Domino’s Pizza

DPZ,

Hershey

HSY,

Wynn Resorts

WYNN,

Kellogg

K,

General Mills

GIS,

Darden Restaurants

DRI,

Clorox

CLX,

… and many others. In total.

You’ve got nearly five times as much of your retirement portfolio invested in Tesla than you do in the entire U.S. home-building industry. And nearly seven times as much as you have invested in the entire U.S. booze industry. It doesn’t end there, either.

If I invest in an S&P 500 Index fund I am betting almost 25% of my money on just six companies: Apple

AAPL,

Microsoft

MSFT,

Amazon

AMZN,

Alphabet

GOOG,

and Facebook

FB,

as well as “Mr. Musk’s Wild Ride.”

My question isn’t so much whether I should invest in these companies at all–it is why I should invest so much in them at the expense of everything else.

“There’s no really clear-cut right or wrong answer to this,” Matthew Bartolini, head of ETF research at index fund giant State Street Global Advisors, tells me. “It all depends on what your beliefs are.”

The simplest, most obvious alternative to these traditional index funds seems to be so-called “equal weighted” portfolios, which (as the name implies) invest your money equally across different stocks.

Bartolini argues that equal weighting has its benefits. But, he says, equal weighting isn’t a magic bullet either. Equal weighting, he says, leaves a portfolio more exposed to smaller stocks and to so-called “value” stocks, meaning those cheaper in relation to company fundamentals such as revenues, earnings or assets.

While State Street offers some equally-weighted funds, focused on the stocks within various sectors and industries, the firm’s flagship SPDR S&P 500 ETF

SPY,

is based on the market value of individual stocks, so that the six most ‘valuable’ stocks account for nearly 25% of the portfolio.

The same is true at most index companies, such as Vanguard. The flagship Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund

VTSMX,

is more broadly diversified than the S&P 500 because it owns more than 3,500 large, medium and small stocks. But the six biggest stocks account for nearly 19% of the portfolio.

Vanguard senior investment Chris Tidmore says that if you hold an equally weighted portfolio instead, you’re betting that the market overall has it wrong. “You’re systematically saying that large companies are overvalued and small companies are undervalued,” he says.

Well, maybe.

A cynic might argue that capitalization-weighted funds work best for the fund industry, because they are most easily ‘scalable.’ It’s easier to add another $1 billion to a fund that invests most in the biggest, most easily-traded stocks.

On the other hand, if each stock offers the same “risk-adjusted prospective return,” as the index crowd tells us, then surely it makes the most sense to bet the same amount on each one? Let’s say for the sake of argument that Tesla stock (1,200 times last year’s earnings) is no better or worse a bet that, say, home builder D.R Horton

DHI,

at just 12 times last year’s earnings. Then why should I invest 20 times as much in Tesla as in D.R. Horton? That’s what’s happening.

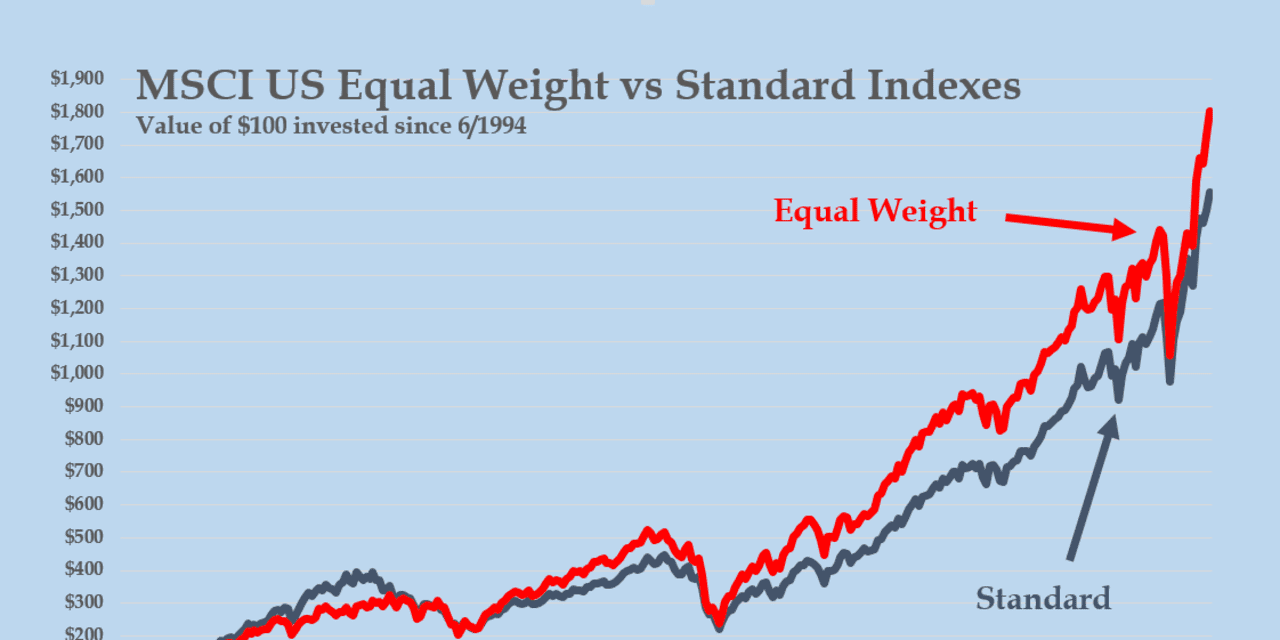

There is precedence for this question. Since the mid-1990s MSCI, the market data company, has been tracking “equally weighted” indexes as well as the standard “capitalization” (or size) weighted portfolios.

The result? Since 1994, the MSCI Equal Weighted portfolio has beaten the standard portfolio by an average of 0.6 percentage points a year, compounded. Or, to put it another way, after 27 years it’s left you almost 20% richer. (Though it should be noted that that has come with more volatility.)

If we look even further back, the strategy would have worked even better. In a study published almost a decade ago in the Journal of Portfolio Management, researchers simulated equally weighted stock portfolios going back to 1964. Their findings? In a series of random simulations, equally weighted portfolios beat the traditional indexes 96% of the time, with an average margin of 1.6 percentage points a year.

There are two equal weight funds that catch my eye, because of their broad global diversification and low costs: The iShares MSCI USA and Japan Equal Weighted ETFs —

EUSA,

and

EWJE,

— spread your bets equally across 600 U.S. and 300 Japanese stocks respectively. So, logically, investing a third of my portfolio in EUSA and two thirds in EWJE would leave me owning more than 900 different companies on two continents, covering most of the two biggest stock markets in the developed world… while paying just 0.15% a year in fees.

I’ve heard worse ideas.