This post was originally published on this site

The Issue:

The pandemic has caused substantial changes in postsecondary enrollment patterns. Almost all colleges have undergone changes to their modes of teaching and learning, moving to online education. This has driven declines in enrollments, a situation that differs from the normal pattern in which undergraduate enrollments typically rise during recessions.

In the short term, these enrollment pressures have damaged institutional finances and strained labor relations within higher education. Over a longer horizon, delayed or foregone educational attainment represents a loss to the overall economy.

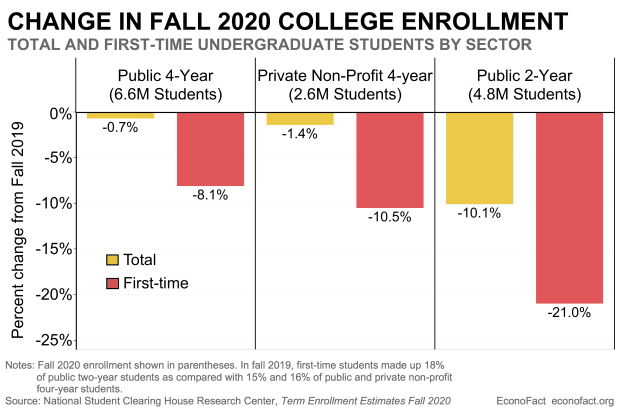

Student enrollment declined with the pandemic, particularly for new college students. The size of the impact varied across institution types.

The Facts:

Postsecondary enrollments fell during the fall of 2020, especially at two-year colleges, as prospective students changed, delayed, or canceled plans to pursue education. According to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (NSCRC), fall 2020 undergraduate enrollments fell 3.6% below those of the prior year. Losses were especially large (8.4%) among those seeking associate degrees with enrollment at public two-year institutions falling 10.1%.

By contrast, enrollments at online institutions rose. The NSCRC found that primarily online institutions—those at which at least 90% of pre-pandemic students enrolled exclusively online—were well positioned for the pandemic and saw undergraduate enrollments increase 4.9%.

Early reports of spring 2021 enrollment suggest a continuation or amplification of these trends. For example, total undergraduate enrollments are 4.5% lower than spring 2020, down 9.5% at community colleges, but they are up 7.1% at primarily online institutions.

“

In normal times college is a very profitable investment, yielding an implicit return of 14%. However, reduced job opportunities during the pandemic increased the rate of return of college by 20%.

”

While all race/ethnicity groups recorded declining enrollments, changes relative to pre-pandemic trends were particularly pronounced among Black and Native American students. Native Americans fared the worst, with a 9.6% drop compared with a 5.6% decline in 2019, while African-Americans’ rate of enrollment decreased by 7.5% as compared with a 4.6% decline the previous year. The largest deviation from trend was seen among Hispanics, whose attendance increased by 1.4% in 2019 only to fall by 5.4% in 2020—a change of 6.8 percentage points.

Enrollments differed markedly between potential new college students and those already in the higher-education pipeline. For example, according to the NSCRC fall 2020 report, graduate- and professional-school enrollments increased 3.6%. By contrast, first-time postsecondary enrollment fell precipitously—off more than 13% overall and down more than 20% at public two-year colleges. First-time enrollment among adult learners (over age 24) fell by almost one-third.

International-student enrollments were dramatically curtailed in the 2020-21 academic year due to choices not to travel, government travel restrictions, and visa restrictions during the pandemic. Shorelight reports wide variation in exposure to financial risks associated with international enrollment; several institutions have more than $100 million in tuition revenue accounted for by students from countries facing travel bans or restrictions.

According to the Institute of International Education (IIE), in fall 2020 international-student enrollments (online and in person) fell 16% while new international-student enrollments dropped 43%.

The IIE reports that more than two-thirds of colleges and universities changed course schedules or teaching methods to mitigate these enrollment effects (changes facilitated by relaxations to Department of Education regulations concerning online instruction). For example, colleges made changes to the schedules to make them work for people in different time zones, and the majority of instruction was available online. More than half of new international enrollments took place online from outside the country, which suggests that losses might have been larger had institutions not adapted.

However, because so many new students studied online, the number of new, on-campus international enrollments fell by 72%.

When students delay their education by taking a gap year, their economic losses in terms of delayed earning potential affect not only their own lives but also the economy as a whole.

Economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York estimate that individuals choosing a gap year in the pandemic gave up $90,000 in lifetime earnings. They note that in normal times college is a very profitable investment, yielding an implicit return of 14%. However, reduced job opportunities during the pandemic increased the rate of return of college by 20% during the past year because of the drop in foregone earnings during a recession.

When the private opportunity cost is applied to the total enrollment reduction of 560,000 undergraduates, aggregate losses reach $50 billion even if every student were to resume studies in fall 2021.

Common Application data through March 1, 2021, suggests a potential recovery in fall 2021 enrollments, though some student subgroups and some types of institutions may continue to see shortfalls. Overall, the Common App reports applications rose 11% year-over-year (counting only applications to institutions using the Common App in both fall 2020 and fall 2021). However, the number of unique applicants held more or less steady—up 2%.

Despite the overall increase, the number of applicants claiming first-generation status fell by 1%; those receiving application fee waivers rose by 1%. If the experience of the approximately 900 Common App schools is representative of higher education as a whole, these figures raise questions about whether disruptions to college attendance in these subgroups initiated by the pandemic may persist for more than one year.

Common Application data also suggests a potential shift in student preferences between institution types; applications to colleges and universities with enrollments greater than 20,000 grew by 17% while those to schools with less than 1,000 students fell by 1%.

The interpretation of Common App data is complicated by several factors. The application season is not yet complete, and institutions may have changed other admissions practices (e.g., waiving standardized tests or adding or eliminating other application platforms) in a way that alters engagement with the Common App. In the context of a pandemic that canceled on-campus tours, students may also have adjusted their application strategy.

Declining enrollments coupled with stresses associated with mitigating the many costs of the pandemic have strained institutional finances and working relationships among faculty, staff, and administrators. Paul Friga, an associate professor of strategy at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, estimates that the pandemic has cost higher education $183 billion—nearly half of which is accounted for by lost tuition revenue. The Department of Labor reports that 650,000 (or one-in-eight) higher-education jobs were lost during 2020. Though analysts report losses to be greatest among lower-paid staff, faculty lines are not immune and some institutions have pointed to the pandemic as justification for effectively eliminating tenure.

In response, faculty have increasingly sought collective action through forming chapters of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP)—organizations that promote collective action among faculty. In 2020, the AAUP reported 69 new chapters, an increase of 10% over the prior year.

What this Means:

Declining enrollments in response to the pandemic pose challenges for higher education and the broader economy. Even before the pandemic, analysts questioned the financial sustainability of large numbers of colleges and universities. In the Great Lakes and Northeast in particular, institutions grappled with the consequences of prior years of low fertility—a problem expected to affect the higher-education market throughout the country in the mid-2020s.

Even though the pandemic is recognized as a temporary challenge, some predicted numerous closures as tuition-dependent institutions experienced abrupt enrollment declines. Fortunately, Higher Ed Dive reports that only a dozen colleges have announced intentions to close since the WHO declared the beginning of the pandemic. Even so, the effects of the pandemic on higher education institutions and the economy as a whole will likely be long-lasting.

Nathan Grawe is a professor of economics at Carleton College. His research focuses on how family background shapes educational and employment outcomes.

This commentary was originally published by Econofact.org—How Have Colleges Fared During COVID-19?

More on colleges & COVID

Community colleges and their students were already vulnerable. Then the pandemic hit

How do you pick a college during COVID? Five critical questions to ask every school