This post was originally published on this site

After decades of slipping union membership rates, labor organizers and their supporters hoped to reverse course, in a small but meaningful way, at an Amazon

AMZN,

warehouse in Bessemer, Ala.

On Friday, as the vote on whether to unionize appeared to have fallen short — though the process is not entirely over — some observers were left wondering: If a very public, closely-watched unionization effort like this fails, what does that mean for the future of unions and organized labor?

Some say it means workers and the unions representing them badly need a re-write on rules stacked against them, while others say the result shows that unions seriously need to re-think what they offer their members.

What the vote “really illuminates is just how extreme the imbalance is in labor law,” said Rebecca Kolins Givan, associate professor in the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations. “It doesn’t particularly tell us whether these workers want a voice at work. It tells us employers are free to bombard workers with messages of anxiety and uncertainty.”

For more than half a century, “the balance of labor law has been in favor of employers and it’s been getting worse over the years,” Givan said.

The highest-profile union drive in years

The unionization effort at Amazon was high-profile from the start.

President Joe Biden, never shy about his pro-union views, emphasized workers should cast their vote on what they think is right, not what their employer thinks. Senator Marco Rubio, a Republican from Florida, said he backed the workers too.

Several Democratic lawmakers travelled to the fulfillment center to show their support. So did celebrities, including actor Danny Glover and rapper Killer Mike.

Amazon kept the voting process in the news cycle with a feisty Twitter

TWTR,

spat.

And the vote happened one year into the COVID-19 pandemic, which has underscored the need for workplace safety in all types of jobs, from meatpackers and retail workers to teachers and warehouse workers.

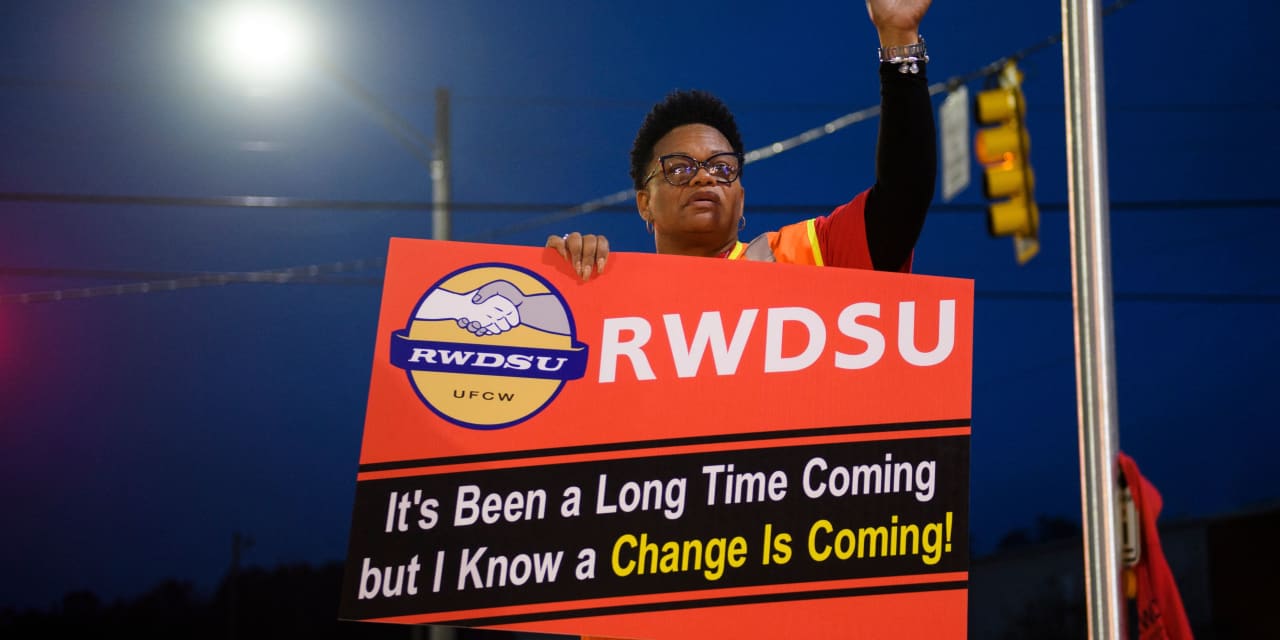

On Friday, the union drive appeared to have failed. Among 5,876 eligible voters at the warehouse, 738 voted to join the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU) and 1,798 voted against the idea. 76 ballots were voided and 505 ballots are challenged, according to the National Labor Relations Board.

To be clear, the voting process isn’t over. The RWDSU says it will challenge the results, alleging Amazon wrongly interfered in the vote and resorted to pressure tactics like forcing employees to attend lectures that were “filled with mistruths and lies” about unionizing.

“Dozens of outsiders and union-busters” walked the floor while workers received company text messages about the vote and a ballot drop-box on warehouse grounds unfairly put workers in the spotlight, said RWDSU President Stuart Appelbaum.

Amazon says it didn’t try intimidating anyone. “Our employees are the heart and soul of Amazon, and we’ve always worked hard to listen to them, take their feedback, make continuous improvements, and invest heavily to offer great pay and benefits in a safe and inclusive workplace,” it said. “We’re not perfect, but we’re proud of our team and what we offer, and will keep working to get better every day.”

Who knows best what workers want?

Rachel Greszler, a research fellow at the right-leaning Heritage Foundation, says the apparently failure of the union drive is another sign that workers aren’t buying what unions are selling.

Though workers want more flexibility and chances for promotions without weighing factors like seniority, unions are wedded to “old ways that lead to more rigid payscales and not more flexible jobs,” she said.

Last year, 10.8% of wage and salary workers were union members, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In the short term, that’s slightly up by 0.5% year over year — but the agency noted the numbers are skewed because 2020’s massive job hemorrhage of all workers meant there were fewer non-union workers to compare against unionized workers.

In the long term, it said the 10.8% membership rate is down from 20.1% in 1983, the first year of comparable data.

The decline in collective bargaining has translated to a loss of $1.56 per hour worked for the median worker, the equivalent of $3,250 for a full-time, full-year worker, according to he Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank. “It has also contributed to the widening wage inequality gap, as unions disproportionately benefit low-wage earners,” EPI said.

This is one vote, but it has outsized symbolism, said Michael Strain, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute. “The fact that labor not only lost, but also lost in such a dramatic and decisive fashion, I think, will take the wind out of the sails of organized labor to an extent.”

Did Amazon make its views crystal clear to worker and even apply pressure? Yes, Strain said. But the workers had to weigh the prospect of potential salary, benefit and working condition gains against “the chance they wouldn’t have a job anymore,” he said. “I think the job was sufficiently attractive as is, that they didn’t want to mess with a good thing.”

Don’t write the obituary for organized labor yet

Anytime a closely followed union drive falls short, “It’s almost always framed as the death of organized labor,” said Celine McNicholas, director of government affairs at EPI.

That’s not the case, she says.

To be sure, a worker deciding whether to unionize or not makes their own choice on what to do, McNicholas acknowledged. But, she added, “are they making it based on fair, accurate, honest information” or is it “disinformation” fed by the employer?

Like Givan, the Rutgers professor, McNicholas says the vote reveals the need for systemic change. That’s why she supports the PRO act. The bill, which passed the Democrat-controlled U.S. House of Representatives last month, would, among other things, penalize companies that violate workers’ rights.

That’s a much-needed departure from the lack of consequences now, said McNicholas. Right now, if a company is found to have wrongly fired a worker for labor-related matters, it “may end up owing back pay. That’s it.”

‘A pretty tough nut to crack’

It’s difficult to read the tea leaves on the future of organized labor based on one vote, said Glenn Spencer, senior vice president, in the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s employment policy division.

Alabama has a low unionization rate (between 5% and 9.9%, according to the Pew Research Center) and Amazon already offered a $15 minimum wage — a recurring call in many recent unionization drives. “This was going to be a pretty tough nut to crack,” he said.

Spencer and the Chamber didn’t take a position on the Bessemer vote, or whether workers should or shouldn’t unionize in other cases. However, the business group is against the PRO Act. “We think it’s bad for workers. We think it’s bad for employers. We think it’s bad for the economy,” Spencer told MarketWatch.

As far as the Bessemer vote and the PRO Act, Spencer said, “I don’t think that this offers you evidence that you need to rewrite the entire system of labor law.”

It remains to be seen whether and where more unionization efforts will crop this year and beyond, Givan said. But even if there aren’t formal unionization drives, that doesn’t mean workers are going quiet. There are still tactics like walkouts to broadcast worker demands, she noted.

The same day the National Labor Relations Board announced the Bessemer vote, Google

GOOG,

workers sent a letter to top management, saying years after a mass-walkout, demands to halt sexual harassment still weren’t being met.

Amazon shares closed Friday at $3,372.20, up 3.54% year to date. The Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

is up more than 10% in that time and the S&P 500

SPX,

is up nearly 12%.