This post was originally published on this site

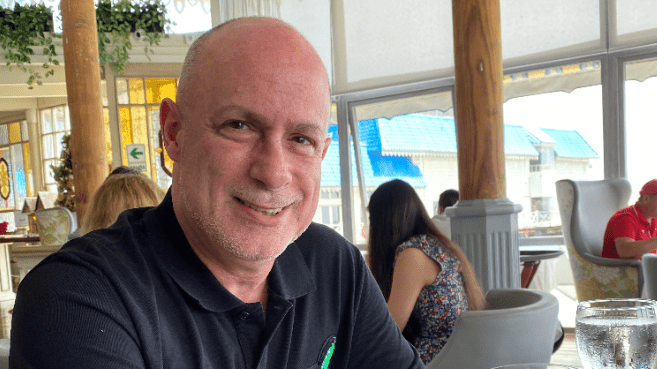

Neil Schwartzman is used to getting vaccines in order to travel to exotic parts of the world such as the Great Rift Valley of Kenya and Ko Pha Ngan in Thailand.

Over the past 30 years, he has meticulously maintained a vaccination record book to ensure he can safely visit the countries he’s traveling to — and it is often a requirement.

Before the pandemic, Schwartzman, 60, who is based in Montreal, traveled to nearly five countries in a given year. But since he’s diabetic, which puts him at increased risk of contracting a severe case of COVID-19, he’s hardly left his home this past year.

He received his first vaccine dose on March 26 and expects to get his second no later than July.

Schwartzman “fully anticipates” he’ll be able to take a September trip he’s in the process of booking to Winnipeg and Churchill, cities located in the Manitoba province of Canada, to observe the Northern lights.

“

Before the pandemic, Neil Schwartzman, 60, who is based in Montreal, traveled to nearly five countries in a given year.

”

Even though he won’t be venturing outside of Canada, he’s fairly confident he’ll need a “vaccine passport”, a digitized or print certificate that proves an individual has been fully-vaccinated, to enter the region that has one of the lowest infection rates in the country, according to government data.

Vaccine passports are “not only reasonable,” he said but “would make me a heck of a lot more comfortable doing things in public.”

Travelers like Schwartzman may view the development of vaccine passports as critical to resuming their excursions across the globe. But vaccine passports have many practical applications outside of vacationing. At the same time, experts warn there could be significant health risks and equity concerns associated with these “passports” that outweigh the benefits.

Neil Schwartzman, pictured, in Lima, Peru, in January, 2020. That was the last trip he took before the pandemic.

Neil Schwartzman

How vaccine passports have worked in the past

Vaccine passports and requirements are not a new concept, especially for people who have traveled to a tropical location overseas.

“The reason we have to get vaccinated against yellow fever to go to Brazil, for example, is that the Brazilian government says, ‘No vaccine, no entry,’” said William Schaffner, professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University.

Also known as the “Yellow Card,” the International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis functions similar to a vaccine passport. The document, nicknamed based on its yellow color, is filled out by physicians who administer vaccines required for entry by different countries. It is most commonly used for the yellow fever vaccine, but any vaccine approved by the World Health Organization can be listed on the document.

“

‘The Brazilian government says, ‘No vaccine, no entry.”

”

But there are widespread issues of forgery. For instance, in Zimbabwe it’s estimated that some 80% of yellow cards are counterfeit, according to an Oct. 2020 study published by the WHO.

“As international borders begin to reopen, COVID-19 vaccine requirements may be introduced, similar to certain destinations that currently require a negative COVID-19 test for entry,” said AAA’s senior vice president of travel Paula Twidale.

“For now, it is unclear what direction airlines and government regulators will go with this.”

Via Rail, the train company Schwartzman has chosen for his two-day glass-bottom train trip to Churchill, declined to comment on whether it will require passengers to have a vaccine passport.

But Philippe Cannon, director of public affairs at Via Rail, told MarketWatch that “passengers will be denied boarding our trains if they are experiencing symptoms similar to a cold or flu or if they have been denied boarding for travel in the last 14 days due to medical reasons related to COVID-19.”

COVID-19 vaccine passports will look different

With COVID-19, policymakers and corporations are taking a decidedly digital approach to the creation of a vaccine passport.

On Friday, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced the launch of Excelsior Pass, a digital platform developed through a partnership with IBM

IBM,

that enables individuals to store digital proof of test results and/or vaccine status, and businesses and venues to verify these items without accessing personal-health data.

“The reopening of key economic activities in New York State, such as arts and entertainment venues, stadiums and arenas, and weddings and catered events, will require proof of a vaccine or negative test for attendees,” a notice posted on the New York Health Department’s site states.

“

Attendance at arts venues, stadiums and arenas, and weddings and catered events, will require proof of a vaccine or negative test.

”

The system utilizes health records captured by the state’s government — eliminating the possibility of someone forging a document, according to a spokesman for the governor’s office. Users sign up online, and the system pulls the relevant health information from the government database to verify the person received a negative COVID-19 test result or one of the available vaccines.

Excelsior Pass then generates a QR code, which can be scanned to grant them entry to facilities participating in the program. The QR code can be displayed in a mobile app, but residents have the option to print out a copy instead.

The system utilizes blockchain technology and encryption as safeguards against sensitive information falling into the wrong hands, but a governor’s office spokesman also noted that sensitive medical information is not stored on the app itself.

New York has rolled out Excelsior Pass, a digital platform that state residents can use to show proof of their COVID-19 vaccination status or that they tested negative to the virus.

New York Governor’s Office

The system was designed to make it easier to access spaces that will require negative COVID test results or proof of vaccination as the state reopens, a governor’s office spokesman said. It also eliminates the risk of losing one’s CDC vaccine card or medical paperwork that contains personal information.

Separately, the World Economic Forum is collaborating with the Commons Project Group, a Swiss nonprofit group, to launch a mobile application, CommonPass, where users can upload their COVID test results and vaccination records.

That will enable them to “consent to have that information used to validate their COVID status without revealing any other underlying personal-health information,” according to information published on the Commons Project website.

“

The World Economic Forum is collaborating with the Commons Project Group to launch a mobile application, CommonPass.

”

“The framework will assess whether the individual’s lab test results or vaccination records (1) come from a trusted source, and (2) satisfy the health-screening requirements of the country they want to enter. The framework delivers a simple yes/no answer as to whether the individual meets the current entry criteria, but the underlying health information stays in the individual’s control.”

CommonPass did not respond to MarketWatch’s inquiry regarding how the app could detect forged or fraudulent vaccination and/or health records.

It’s unclear how the U.S. will rollout nationalized vaccine passports, if at all. White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki told reporters Monday that “there’s currently an interagency process that is looking at many of the questions around vaccine verification.”

The initiative, she said, will be spearheaded by the private sector. But “there’ll be no centralized universal federal vaccinations database, and no federal mandate requiring everyone to obtain a single vaccination credential.”

As of now New York’s Excelsior Pass remains exclusive to New York state residents, given that it’s based on the state’s own COVID-19 data. But a governor’s office spokesman said that the state’s government views expanding the system to neighboring states as one of the next steps for the program.

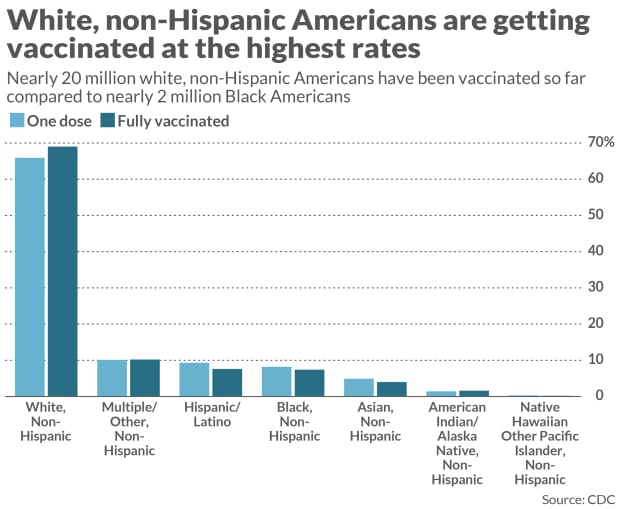

In the U.S. nearly 70% of more than 52 million people who have been fully vaccinated against coronavirus are white and non-Hispanic as of Tuesday, according to data published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Despite getting hit hardest by coronavirus, both from a health and economic perspective, Black and Latino Americans are disproportionately getting vaccinated at lower rates compared to white, non-Hispanic Americans.

During President Joe Biden’s first full day in office, he pledged to level the playing field for minorities by opening more federally-run and mobile vaccination sites in hard-hit communities.

Research shows that Black Americans on average have to travel further than white Americans to get vaccinated, according to findings published in February by University of Pittsburg researchers.

On top of this, Black Americans in particular are more hesitant to get vaccinated. Some of that hesitancy stems from mistrust of the medical establishment, the result of a history of medical racism and experimentation on people of color.

“

In the U.S. nearly 70% of more than 52 million who have been fully vaccinated against coronavirus are white and non-Hispanic.

”

In February, 22% of American adults indicated that they want to “wait and see” how the shots work for other people before they get vaccinated themselves, according to polling by the Kaiser Family Foundation, a health-policy think tank. That’s down from December when some 39% of Americans said they’d wait and see.

Among Black and Hispanic adults 34% and 26% of respondents fell into the wait-and-see category in February, according to KFF.

Taken together, while vaccine supply is still limited, if vaccine passports are widely used not only for travel but for other social events such as concerts, broadway shows, nightclubs, it would “double privilege” people got vaccinated early on, said Christine Whelan, clinical professor in the School of Human Ecology at UW-Madison.

What’s more: If different communities are receiving contradictory messages regarding vaccine effectiveness and potential side-effects, vaccine passports could ultimately “be a slippery slope for deepening equity gaps.”

“Allowing them to do special things because of that just doesn’t sit quite right,” said Whelan, who is chief happiness officer at Dear Pandemic, a science-communication project.

At the same time, “it’s a little bit difficult because you want to encourage people to get vaccinated,” she said. “Offering rewards and ability for people who are vaccinated to do more of the things that they want to do in the abstract is perfectly good.”

Vaccine passports and risky behavior

In a paper released in February, the WHO came out against governments establishing COVID-19 vaccine requirements for international travel, citing in part the unknowns associated with the vaccines that have rolled out.

“There are still critical unknowns regarding the efficacy of vaccination in reducing transmission,” WHO noted in the report. “In addition, considering that there is limited availability of vaccines, preferential vaccination of travelers could result in inadequate supplies of vaccines for priority populations considered at high risk of severe COVID-19 disease.”

“

‘There are still critical unknowns regarding the efficacy of vaccination in reducing transmission.’

”

As CDC adviser Schaffner notes, vaccines “don’t provide you with a suit of armor of total protection.” While evidence thus far shows that the vaccines are very effective at preventing serious infection or hospitalization as a result of COVID-19, less is known about whether vaccinated individuals can still be carriers for the virus and spread it.

And from a global perspective, different countries have authorized different vaccines.

“Would American Airlines accept somebody who comes in with a certificate who’s been vaccinated by Sputnik V, the Russian vaccine, or Sinovac, the vaccine manufactured in China?” Schaffner said. “Who is to say whose vaccine is going to be acceptable, but that opens up a whole other can of worms.”

A more recent wrinkle for vaccine passports is the rapid spread of variants of the virus that causes COVID-19. Evidence suggests the vaccines on the market may not be as effective at combating these variants, reducing their efficacy. Drugmakers like Pfizer

PFE,

and Moderna

MRNA,

are already experimenting with booster doses of their vaccines to target the newer variants.

“The whole concept here is to create as low-risk environments as possible, but the changing environment may be such that last year’s vaccine is out of date,” Schaffner said. “It’s not as clean as the yellow fever vaccine was for international travel.”