This post was originally published on this site

Would you like to know whether the S&P 500’s earnings per share will accelerate in coming years?

Of course you would. Earnings growth is the fuel on which the stock market runs. You’d overweight equities if earnings growth were about to accelerate—and underweight them (or get out of stocks altogether) if earnings growth were about to slow.

I’m not so sure this is a good strategy, however. An examination of U.S. stock market history casts doubt on how valuable it would be to have perfect foreknowledge of future earnings growth rates

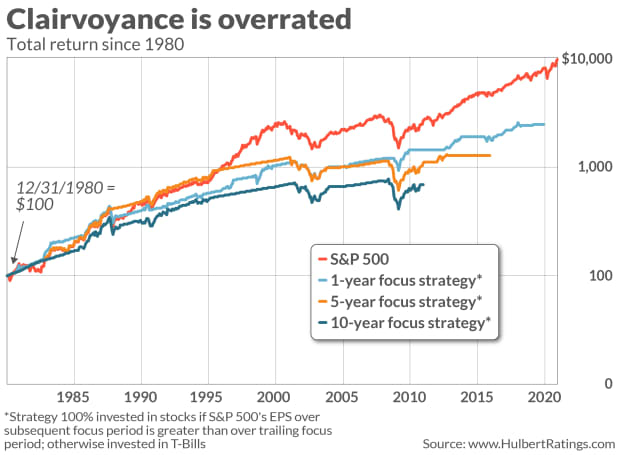

Consider how much money you would have made over the last four decades if, each month along the way, you had perfect foreknowledge of whether the earnings growth rate was accelerating or decelerating. Specifically, I imagined that, each month since 1980, you knew whether the S&P 500’s

SPX,

earnings per share over the subsequent 12 months would grow at a faster pace than over the trailing 12 months. If so, then you would be 100% invested in an S&P 500 index fund; otherwise you would invest in T-bills.

Note carefully that you’d have to have considerable clairvoyance to be armed with such foreknowledge. The S&P 500’s earnings are reported with a couple- month lag, so this foresight would require being able to see 14 or 15 months into the future.

Unfortunately, however, this foresight would have done you no good. This hypothetical portfolio would have produced an 8.6% annualized total return over the last four decades, well below the 12.0% annualized growth of buying and holding. This remarkable prescience would have cost you 3.4 annualized percentage points.

Might it be that a one-year look-ahead period is not long enough? To test for that, I constructed a second hypothetical portfolio that focused on having foresight five years into the future. This second portfolio was 100% invested in the S&P 500 whenever the EPS’ growth rate over the subsequent five years was higher than over the trailing five years, and otherwise in T-bills. This portfolio did not do any better than the one-year foresight portfolio. And, as you can see from the accompanying chart, the same goes for a strategy whose focus period was 10 years.

Uncredited

These results are very similar to those that analyzed the relationship between the economy and the stock market. As I reported in a column a couple of years ago, “you could still lag the U.S. market even if you had perfect insight into future U.S. GDP growth.” I based that column on research conducted by Vincent Deluard, head of global macro strategy at investment firm StoneX.

Why is perfect foreknowledge of earnings growth or the economy so unhelpful? “The simple explanation,” according to Nicholas Rabener, founder & CEO of FactorResearch, “is that investors are irrational and stock markets are not perfect discounting machines. Animal spirits matter as much if not more than fundamentals. The tech bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s is a great example of this. Many highflying companies of that era like Pets.com or Webvan had negative earnings but soaring stock prices.”

GameStop

GME,

of course, is a more current example. But the point is the same.

These results provide yet more evidence of why it’s so hard to beat the market. Unless you can forecast the ways in which investors will be irrational, and the ways in which the market will be imperfect in discounting the future, the default choice for the equity portion of your portfolio should be an index fund.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com