This post was originally published on this site

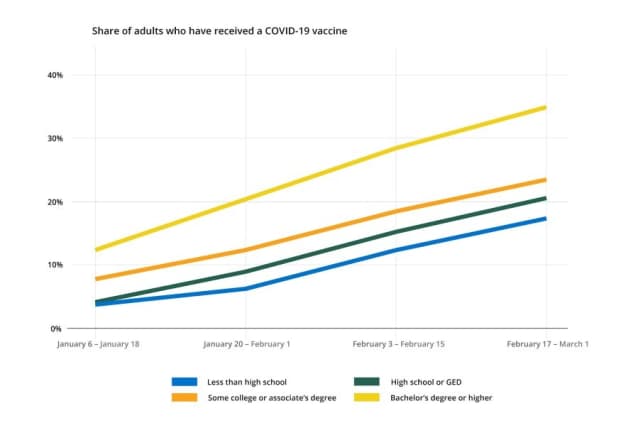

People with college degrees are more likely to have been vaccinated than their non-college educated peers, researchers at Georgetown University found.

That’s likely because the first phase of vaccine rollouts prioritized essential workers, a group that includes health-care workers, who are more likely to have bachelor’s degrees than other essential workers.

“

Health-care workers, who are more likely to have bachelor’s degrees than other essential workers.

”

The term “essential worker” describes the group of workers that were called to work in person when the majority of the economy was shut down to curb the spread of coronavirus. It includes grocery store workers, public-safety workers, sanitation workers, bus drivers and health care professionals.

In total 48 million Americans are essential workers, making up roughly 43% of the U.S. workforce, the Brookings Institution, a left-leaning think tank, found. Some 70% of essential workers don’t have a college degree, according to the Economic Policy Institute, a progressive think tank.

Some 30% of the more than 85 million Americans who have received at least one COVID vaccine dose so far have at least a bachelor’s degree, according to research published Wednesday by Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, an independent, nonprofit research and policy institute.

Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from US Census Bureau

In contrast, some 20% of Americans who’ve received at least one dose have a high school diploma or GED.

Essential workers within the health care sector are more likely to have a college degree compared to non-healthcare essential workers.

“

Some 70% of essential workers don’t have a college degree

”

That helps explain why “adults with bachelor’s degrees or higher were more likely to be vaccinated because the first phase of distribution prioritized healthcare workers,” according to the Georgetown report.

Prioritizing health-care workers before all other types of essential workers “may have contributed to equity gaps in vaccine access for Black and Latino communities, which have been hit hard by COVID-19,” Anthony Carnevale, director of the CEW, and Megan Fasules, a research economist at CEW, wrote.

Essential workers are more likely to be people of color: 16% of essential workers are Black and 21% are Hispanic, compared to all other sectors of the workforce, where 10% of workers are Black and 15% are Hispanic, according to Brookings.

However, while Black and Latino workers are overrepresented in many essential frontline jobs, they are “underrepresented in the healthcare professional occupations in which workers qualified earliest for vaccine eligibility,” according to the Georgetown researchers.

“

Essential workers are more likely to be people of color: 16% of essential workers are Black and 21% are Hispanic, compared to all other sectors of the workforce, where 10% of workers are Black and 15% are Hispanic

”

Besides giving health-care workers priority access to COVID vaccines, there are several other factors that help explain why nearly 70% of the 46 million Americans who have been fully-vaccinated thus far are white and non-Hispanic.

For instance, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh found that on average Black Americans have to travel farther to vaccination sites from their homes than white Americans. That’s especially problematic for people who don’t own a car.

Access to high-speed internet, which minorities are less likely to have, may also be contributing to the inequitable vaccine distribution rates, because it makes it harder to schedule vaccine appointments, Carnevale and Fasules said.

Vaccine hesitancy, in many cases stemming from deeply-rooted mistrust of the medical establishment, the result of a history of medical racism and experimentation on people of color, may also be contributing to the racial disparities in vaccine administration.

There are also partisan divisions. About 44% of Republicans say they will definitely or probably not get vaccinated, compared with 17% of Democrats.

Overall, some 22% of American adults indicated that they want to “wait and see” how the shots work for other people before they get vaccinated themselves, according to polling by the health-policy think tank Kaiser Family Foundation. That’s down from December when some 39% of Americans said they’d wait and see.

Among Black and Hispanic adults 34% and 26% of respondents fell into the wait-and-see category in February, according to KFF.