This post was originally published on this site

Insider trading is going on in plain sight but instead of being prosecuted, the company insiders involved are commended.

That’s because the insider trading here involves gifts of company shares to charity. Some of these insiders appear to be using privileged information to time when their gifts occur, thereby maximizing their tax deductions. In some cases, the dollar value of their tax deduction exceeds what they would have obtained had they sold the shares directly and pocketed the proceeds.

These are the findings of a new study that is forthcoming in the Duke Law Journal. Entitled “Insider Giving,” its authors are S. Burcu Avci of the Sabanci University School of Business in Turkey; Cindy Schipani and Nejat Seyhun, both of the University of Michigan, and Andrew Verstein of the UCLA School of Law.

An example the authors provide in their study is of a gift of Eastman Kodak

KODK,

stock to charity made last summer by company director George Karfunkel — a gift that perfectly coincided with a six-year high in Kodak’s stock. Shares that traded as low as $2.13 on July 27 rocketed to a high of $60 on Jul. 29 on rumors that the company might secure a government contract to produce COVID-19 vaccines.

Almost as quickly those rumors were dashed and the stock plunged. On Aug. 3, the day (according to an article in the Wall Street Journal) when the company said it was notified by Karfunkel of the gift, Kodak stock traded as low as $14.74. In subsequent filings, Karfunkel reported that the actual date of his gift was July 29, the day of the stock’s high.

This timing here appears questionable. As the study’s authors point out, Karfunkel could have had inside information that “the government deal propping up the stock price was unlikely to materialize.” They furthermore add that, since the gift wasn’t immediately reported, he could have backdated the gift to take advantage of the pre-drop price.

Kurt Jaeckel, Kodak’s Director of Worldwide Communications, said in an email that “Kodak does not comment on the financial activities of its board members.” An email to Karfunkel requesting comment was not immediately answered.

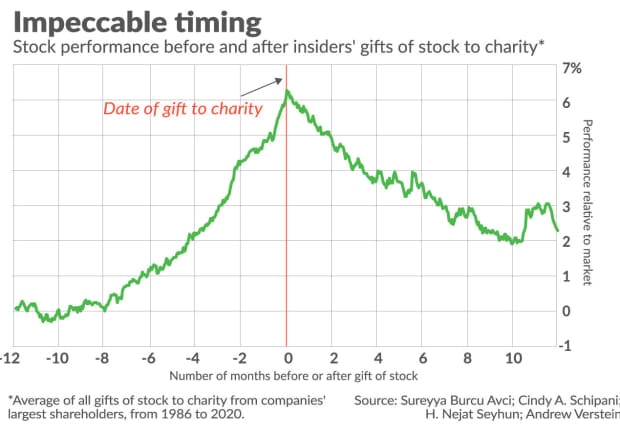

It would be one thing if cases such as this were the exception. But it does not appear to be, according to the study’s authors. Upon analyzing all charitable gifts of stock from companies’ largest shareholders from 1986 to 2020, they found that the average gift was almost perfectly timed. As you can see from the chart below, the average donated stock’s price reaches its highest point, compared to a broad market index such as the S&P 500

SPX,

on the date of the gift — both relative to the 12 months prior to the gift as well as the subsequent 12 months.

The odds that this result could be due to the insiders simply being lucky are vanishingly small, Seyhun said in an interview. The data plotted in the chart reflect an average of more than 9,000 charitable donations of stocks, encompassing 2.1 billion shares with a dollar value of approximately $50 billion.

You might wonder how insiders can backdate their gifts. The answer, according to the study’s authors, is that these gifts can be reported more than 400 days after the alleged effective date of their gifts. That’s far different than for outright insider sales, which must be reported within two business days. The charities themselves, which are grateful to have received any gifts, typically don’t complain that they could have received more value had they actually received the gifts on the day insiders say they made them.

To show the prevalence of backdating, the study’s authors compared the price behavior of stocks whose gifts to charity were immediately reported with those that were only reported after a significant delay. When immediately reported, there was no notable pattern to the stocks’ average performance subsequent to the gift. When reported with a sizeable delay, in contrast, the stocks on average proceeded to significantly underperform the market after the effective date of the gift. Seyhun said that, other than backdating, other potential explanations do not predict such a pattern.

A historical parallel of note: The backdating of insider gifts to charities is reminiscent of the options backdating scandal of 15 years ago. In that scandal, the companies involved, for a variety of accounting and tax reasons, claimed that option grants had been issued to insiders with strike prices that “happened” to coincide with historical prices that maximized those options’ market value. Seyhun, one of the current study’s authors, was also one of the researchers who first documented the extent of that scandal. (I wrote a column about this research for Barron’s in 2006.)

Is such insider manipulation illegal? Yes and no. The study’s authors write that “there are laws that constrain manipulative gifts, but there is no doubt that the law of insider giving is less clear and developed than the law of insider trading.”

You might think that manipulative giving by insiders is not that big a deal. But Seyhun disagrees: It “hurts the corporation and its other shareholders,” he said, and makes “the market a more dangerous place for non-insiders.” Furthermore, it erodes trust in the rest of us that the markets are a level playing field.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: Six ‘reopening’ stocks, including Bumble and Wayfair, that company insiders absolutely love

Also read: Why the health-care sector — not gold — is the best inflation hedge