This post was originally published on this site

The U.S. stock market often struggles during the NCAA “March Madness” college basketball tournament, which shows, yet again, how people’s moods can affect investment decision-making — even when those moods relate to something as otherwise irrelevant as whether your bracket gets busted.

If you are a short-term trader, note that tip-off in the first game of this year’s March Madness is 4 p.m. Eastern time on Mar. 18. The tournament ends with the championship game on the evening of Apr. 5.

The correlation between sports and the stock market was documented by a study published a number of years ago to in the Journal of Finance. Entitled “Sports Sentiment and Stock Returns,” its authors were finance professors Alex Edmans of the London Business School; Diego Garcia of the University of Colorado at Boulder; and Oyvind Norli of the BI Norwegian Business School.

After studying more than 1,100 soccer matches, the professors found that, on average, a given country’s loss in the World Cup elimination stage is followed by its stock market the next day producing a return that is significantly below average. Though they focused primarily on the World Cup, they also studied cricket, rugby and basketball matches as well.

Crucially, the researchers did not find a symmetrically positive stock market impact following a World Cup win. They speculate that this is because a win merely means that a country’s team advances to the next round, while elimination is final. As a result, losing teams’ fans are likely to be more despondent than winning teams’ fans will be exuberant.

The logical consequence of this asymmetry: global stock markets should experience abnormal levels of selling during the World Cup and, therefore, below-average returns. And, sure enough, that is exactly what was found by another academic study, this one by Guy Kaplanski of the Bar-Ilan University in Israel and Haim Levy of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

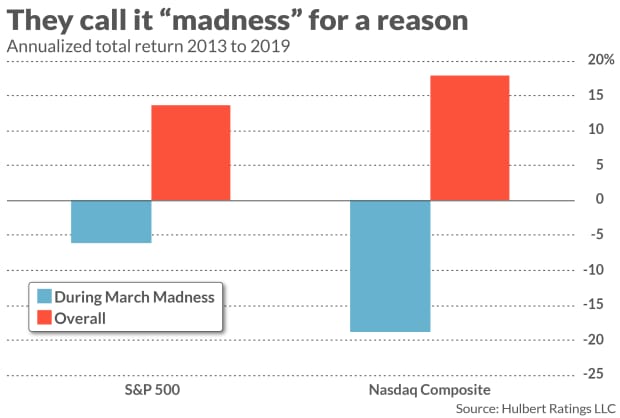

The analogous impact of March Madness is on the U.S. stock market. To test for that, I measured the returns of both the S&P 500 SPX, -0.32% and the Nasdaq Composite COMP, -1.14% during the past seven tournaments prior to 2020. (Last year’s tournament, was cancelled because of the pandemic. I went back seven years prior to 2020 for the statistically sound reason that I didn’t feel like going any further.)

The results are summarized in the chart below. Notice that, at least for the period from 2013 through 2019, the stock market performed significantly more poorly during the March Madness tournaments than the rest of the time.

To be sure, the statistical significance of these results is questionable. Going back to 2009, for example, would have shown better results for the stock market during March Madness, since the 2009-2020 bull market began one week before the start of that year’s tournament. Going back to 2000 would have shown worse results, since the bursting of the internet bubble almost perfectly coincided with the beginning of that year’s tournament.

Yet the psychological significance of these results is undeniable: They show us, once again, how our moods can affect our investments. The lesson is that we should be following pre-determined investment strategies with patience and discipline.

Daylight savings time

If you are a day trader inclined to take some chips off the table before March Madness begins, you might want to do so a few days earlier. That’s because most of the U.S. is shifting to Daylight Savings Time on March 14 and stock market returns around the world tend to be below-average on the day after that shift.

This was the finding of a study that appeared several years ago in the American Economic Review. Entitled “Losing Sleep at the Market: The Daylight-Savings Anomaly,” the study was conducted by Mark Kamstra of York University, Lisa Kramer of the University of Toronto and Maurice Levi of the University of British Columbia. The researchers found that stock market returns around the world are below-average on the Monday following shifts to daylight savings.

To explain this anomaly, the authors point out that “we have all struggled through a day after a poor night’s sleep, weighed down by weariness, fighting lethargy, and perhaps even facing despondency.” And it is not a stretch to imagine that these reactions affect our investment decision-making, since a large body of psychological research that has documented the “effects of changes in sleep patterns on judgment, anxiety, reaction time, [and] problem solving.”

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: Dow 32,000? If dividends counted, the index could be more than 1 million points higher

Plus: If all you did was trade on this one behavior, you could make decent money in the stock market