This post was originally published on this site

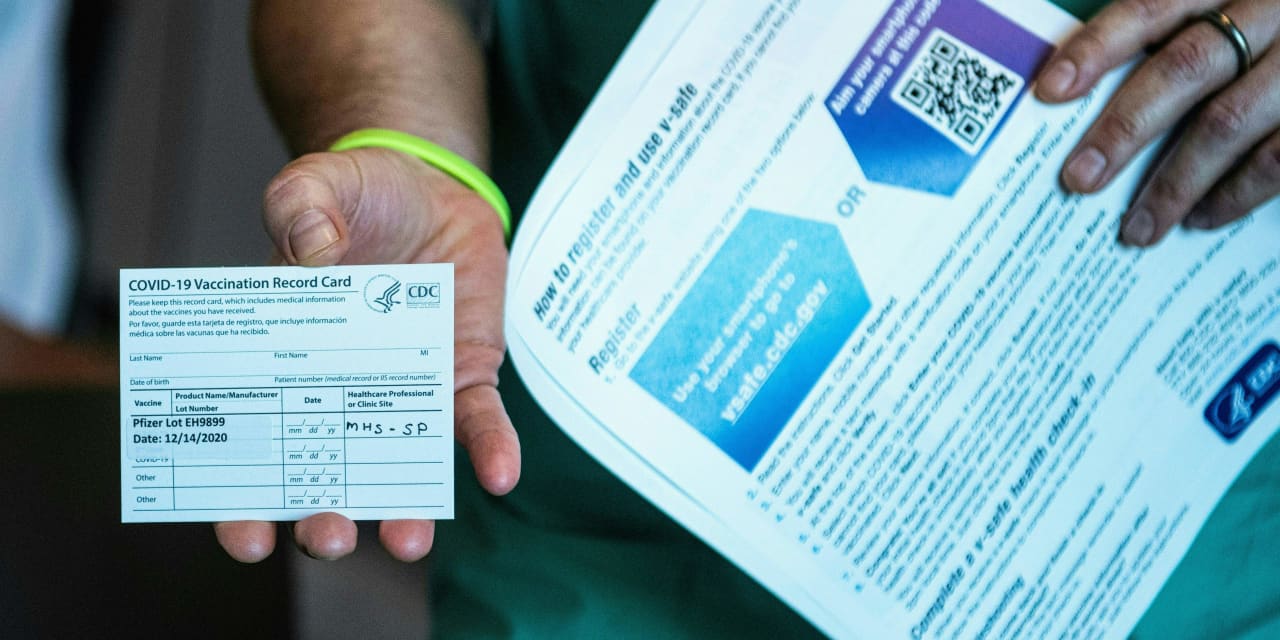

If you got the COVID-19 shot, you likely received a little paper card that shows you’ve been vaccinated. Make sure you keep that card in a safe place. There is no coordinated way to share information about who has been vaccinated and who has not.

That is just one of the glaring flaws that COVID-19 has revealed about the U.S. health care system: It doesn’t share health information well. Coordination between public health agencies and medical providers is lacking. Technical and regulatory restrictions impede use of digital technologies. To put it bluntly, our health care delivery system is failing patients. Prolonged disputes about the Affordable Care Act and rising health care costs have done little to help; the problems go beyond insurance and access.

Breaking news: Misinformation plays an increasing role as state lawmakers push back against public health measures to curb coronavirus

I have spent most of my career within the domain of information technology and IT-based innovation and systems engineering. As a professor of health informatics, I have focused on health care transformation. For two years, I served on the Health Innovation Committee at HIMSS, the pre-eminent global health information and technology organization. In short, I have studied these problems for decades, and I can tell you that most of them aren’t about medicine or technology. Rather, they are about the inability of our delivery system to meet the evolving needs of patients.

We need a high-performance system

In reality, the U.S. health-care sector is not a system at all. Instead, it is an underperforming conglomerate of independent entities: hospitals, clinics, community-health and urgent-care centers, individual practitioners, small group practices, pharmacy and retail outlets, and more, most of which compete for profits and in some cases pay sky-high salaries to executives.

These entities often function in silos. Errors, gaps, duplication of services and poor patient outcomes are often the result.

Here’s an example: A heart-surgery patient, still on oxygen and in intensive care just two days earlier, is referred to her primary-care physician for follow-up, and to a rehabilitation center for therapy. Neither her doctor nor the facility knows the patient was even hospitalized, nor do they have access to her records or medication list.

Also from The Conversation: Money pressures because of COVID-19 may finally push hospitals to stop wasting billions of dollars on supplies

Shopping for doctors

For patients, this might mean a disjointed set of services that don’t offer a coordinated plan of care or even a timely or comprehensive diagnosis of their health problems. Patients with chronic conditions often see more than 10 different doctors during dozens of office visits a year.

The specialist may not even be aware when the patient doesn’t return. Patient information is seldom shared; specialists are often associated with different medical systems that don’t share records. And even when they try, accurately matching patient IDs in different systems can be problematic.

The challenge now is to transform the status quo into a high-performance system, a true 21st-century health-care delivery system. Bringing systems engineering and information technologies to medical practice can help make that happen, but doing that requires a holistic approach.

Let’s start with electronic health records. More than 20 years ago, the Institute of Medicine called for the transition from paper to digital health records. This would allow patients to easily share lab, imaging and other test results with different providers. Nearly a decade went by before action occurred on the recommendation. In 2009, the HITECH Act was passed, which provided $30 billion of incentives for the transition.

Yet now, 12 years down the road, we’re still a long way from a patient’s electronic health records becoming universally available at the point of care. Connectivity across systems and networks remains fragmented, and a lack of trust between organizations, along with anticompetitive behavior, results in an unwillingness to share patient information.

In the news: U.S. COVID vaccine supply to be boosted by Merck helping make J&J vaccine

One failure of the system is an inability to accurately identify and match patient records. Few standards exist for collecting patient information. With hundreds of vendors and thousands of hospitals, doctor’s offices, pharmacies and other facilities participating in the process, variation is huge. Is John Doe at 250 Park Ridge Drive the same as John E. Doe at 250 Parkridge?

In 2017, the American Hospital Association estimated 45% of large hospitals reported difficulties in correctly identifying patients across information technology systems. This means, on occasions at least, clinicians are making decisions that lead to increased chances of misdiagnosis, unsafe medical treatment and duplicate testing.

During a public health emergency such as COVID-19, accurate IDs of patients is one of the most difficult operational issues that a hospital faces. Accurate COVID-19 test results are hampered when specimens, sent to public health labs, are accompanied by patient misidentification and inadequate demographic data. Results can be sent to the wrong patient, or at best, get backlogged.

These mistakes also are costly. More than one-third of all denied claims result directly from inaccurate patient identification or information that’s wrong or incomplete. This costs the average U.S. health-care facility $1.2 million a year.

Congress needs to act

For nearly two decades, the Department of Health and Human Services has been restricted from spending federal dollars to adopt a unique health identifier for patients. To remedy the problem, the House of Representatives in July 2020 unanimously adopted an amendment allowing HHS to evaluate patient identification solutions that still protect patient privacy. But the Senate chose not to address the issue. Still, many health-care leaders are advocating for the new Congress to take action. Health-care proponents are hopeful the new Senate majority leader will be more receptive to addressing the issue.

A bright spot in all of this is that many health-care systems saw the advantages of telemedicine during the pandemic. It’s convenient for patients, it saves money, and it meets the needs of patients who have difficulty traveling. Telemedicine could be just the beginning; with an ever-growing array of mobile health devices, physicians can monitor a patient at home, rather than in an institution.

More must be done, however. Throughout the pandemic, some patients, with a lack of broadband access or poor Wi-Fi, had something less than a rich and uninterrupted visit.

Health IT advocates have long envisioned a health care system that seamlessly uses connected care to improve patient outcomes while costing less. When the pandemic subsides, the waivers and policies temporarily adopted will require not a sudden termination, but a transition to such a system.

Over the past year, doctors, nurses and health-care systems have learned lessons out of necessity. Instead of abandoning our new knowledge, I believe we need to double down on a modern, stable and value-based health-delivery system with equity for all. And at its heart must be one certainty: that accurate and comprehensive patient records are always available at the point of care.

This commentary was originally published by The Conversation—COVID-19 revealed how sick the US health care delivery system really is

Elizabeth A. Regan is the department chair of Integrated Information Technology and professor of health informatics at the University of South Carolina.