This post was originally published on this site

Despite reports of an exodus, Silicon Valley remains the tech capital of the world, with new data showing continued record investment in the industry in 2020 and no overall declines in jobs and population in the region.

While the high-profile departures of rich executives and investors like Elon Musk and companies like Oracle Corp. ORCL, -1.35% and Hewlett Packard Enterprise Corp. HPE, +1.58% have raised questions about the future of California’s tech powerhouse, an annual report out this week found little evidence of a trend. Instead, the major effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the San Francisco Bay Area in 2020 was the widening of the divide between the haves and have-nots, thanks to all the money still flowing into just a few pockets as the coronavirus ravages poorer communities.

“Today, we must frankly admit that the pandemic has made the rich richer while the poor are dying,” said Russell Hancock, chief executive of Joint Venture Silicon Valley, which published its annual Silicon Valley Index this week detailing what happened in the region last year.

The report showed record venture capital investment in Bay Area startups, along with booming market capitalizations for public tech companies and standard-setting initial public offerings. Amid fears of a tech-worker stampede out of the Golden State as companies allowed remote work, the population in Silicon Valley — defined as Santa Clara and San Mateo counties — was mostly flat for the year, rising 0.02%.

While an overall out-migration was tracked in San Francisco, the vast majority of those who left the most prominent city in the region last year remained in the state, according to U.S. Postal Service data crunched by the San Francisco Chronicle this week. That’s in line with what the Silicon Valley Index shows: 59% of the people who have left the valley in the past few years have stayed in California, moving up or down the state.

“I think we can all calm down,” said Rachel Massaro, Joint Venture’s director of research, during a news briefing about the index. “We’re a place of innovation. We’re a place that houses these impactful companies. We have not seen any significant losses among them.”

In short, the region’s biggest companies and highest-paid people fared drastically better and in many cases thrived — white-collar workers, who earn more than three times as those in service occupations, got to work remotely and protect themselves from a deadly virus — while low-wage workers lost jobs and fell ill, their lack of a safety net shining a harsher light on inequality.

“It’s a tale of two economies,” Hancock said. “There are two stories.”

The tech story

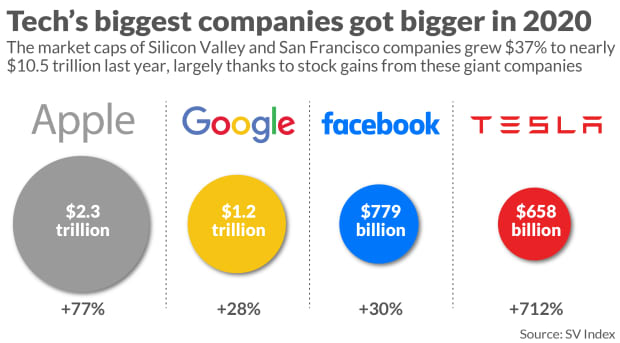

Silicon Valley and San Francisco companies’ market capitalization climbed 37% to $10.5 trillion last year, according to the report, thanks to huge spikes from companies such as Tesla Inc. TSLA, -0.77%, which saw its market cap skyrocket more than 700% in 2020; Apple Inc. AAPL, +0.12%, which saw a 77% increase, while Facebook Inc. FB, -2.91% grew 30% and Google GOOGL, -0.81% experienced a 28% boost.

Big Tech kept getting bigger in other ways as well. The top 15 tech employers in the area — which includes the above plus other large companies like Intel Corp. INTC, +2.27%, Salesforce Inc. CRM, -0.12% and Cisco Systems Inc. CSCO, -1.42% — ended the year with a 3.7% increase in jobs even while the region saw a couple hundred thousand jobs disappear overall. And despite nagging questions about the effects of a work-from-home shift on commercial real estate, the largest companies in the region continued construction on existing projects, such as Google’s planned massive development in San Jose, Calif.

The next generation also received record investment totals. Snowflake Inc. SNOW, +0.05%, DoorDash Inc. DASH, +2.94% and Airbnb Inc. ABNB , all based in the Bay Area, were the three biggest U.S. initial public offerings of 2020, not including special-purpose acquisition companies. And even in a booming year for IPOs, Silicon Valley outperformed the rest: 2020 IPOs from the valley grew 117% and S.F. issuances grew 101%, while IPOs in general returned 80% last year, according to the Silicon Valley Index.

IPOs in 2021: After a year of impressive pandemic offerings, these tech companies expect to keep it rolling

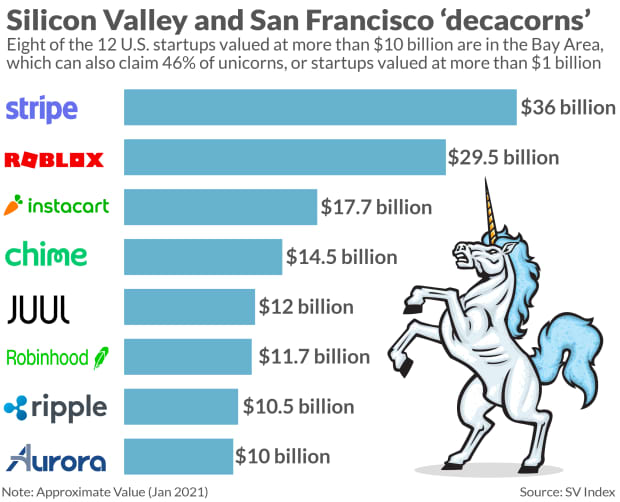

It was also a record year for venture capital, with funding to Silicon Valley and San Francisco companies increasing 8% from 2019, the report said. Of the $123.6 billion in U.S. VC funding in 2020, $26.4 billion went to Silicon Valley, $20 billion to San Francisco and $67 billion to California. A lot of that investment went into well-known startups including Bay Area decacorns (private companies worth at least $10 billion) like Stripe, Instacart and Robinhood.

The other, less positive story

While Big Tech flourished and money continued to pour into potential additions to that group, the gap between those flourishing from that performance and Silicon Valley’s poorer residents is wider than ever, the index shows.

As of last Friday, 2,069 people in the region had died of COVID-19, Hancock said. Death rates were highest among Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, Black/African Americans and Hispanic or Latinos, respectively. A report by the Mercury News showed that death rates were far higher in poorer neighborhoods than wealthier ones, such as in the largely Latino neighborhoods of East San Jose.

Lower-wage workers lost their jobs or had to put their health at risk to hang onto their positions.

“The pandemic wiped out our service sector and in-person economy,” Hancock said. “There’s real carnage out there. People have lost their livelihoods.”

The region’s community infrastructure and service jobs declined 54% by midyear 2020. Hispanic people were 1.5 times more likely to file unemployment claims as white people, Hancock said. And in December, more than 626,000 households in the Bay Area, including nearly 200,000 households in Silicon Valley, were at risk of eviction or mortgage nonpayment, according to the index.

See: How long will the Silicon Valley employees who can’t work from home keep getting paid?

Shuttle drivers who drove tech employees to various offices around the Bay Area for companies such as Salesforce Inc. CRM, -0.12%, Twitter Inc. TWTR, -0.17% and others — which have told their employees they can work remotely permanently or most of the time — have been laid off or furloughed, said Stacy Murphy, business representative for Teamsters Local 853, which represents about 800 shuttle drivers in the Bay Area. Some drivers are still on paid furlough, but others are no longer receiving wages and most have no idea when they can return to work.

“We are all patiently waiting,” said Murphy, who has said the union is in constant discussions and is advocating for the drivers to keep getting paid.

The murky future

Some data from the index shows that concerns about a threat to the region’s reign as a tech center are not unfounded. Although Silicon Valley’s population did not decline in 2020, a yearslong out-migration trend did continue. Still, the index shows that the net out-migration in 2020 was about half that of the departures from the region in 2001, after the dot-com bubble burst.

The index also shows that the employment growth rate of the top 15 largest tech employers in Denver (14.7%) and Sacramento (14.5%) were nearly four times that of the Bay Area’s 3.7%. And the Bay Area’s share of those same companies’ U.S. workforces fell from 26.1% in January 2020 to 23.9% in December. While the percentage gains were smaller, the Bay Area still added more tech jobs in total than the other metropolitan areas.

Metro areas in Florida, Texas and elsewhere are touting themselves as the next big tech hubs as companies and executives move to places like Texas, where Oracle and Hewlett Packard Enterprise Co. HPE, +1.58% have moved their headquarters — even as many Oracle employees remain in the Bay Area, Hancock pointed out.

As other companies move or make decisions about whether their employees should return to the office, it will affect the construction projects that have been put on hold or the office-space rental rates that have mostly held steady.

The Bay Area Council, which includes the region’s companies as members and advocates for business-friendly policies, has launched a “business climate” initiative as it worries about companies leaving the region.

“It’s not going to be an immediate change,” said Patrick Kallerman, research director for the Bay Area Council Economic Institute. “The Bay Area isn’t going to be a ghost town in six months. We’re asking ourselves if this is going to be a long-term, significant change.”

Those changes will affect the quality of life in the Bay Area as municipalities find themselves with budget shortfalls. Silicon Valley city revenues are expected to decline by an average of 5% mostly due to the pandemic’s effects, according to the SV Index. San Francisco saw sales tax revenue decline 43% in the second quarter of 2020 compared with the prior year, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, which looked at the effects of the pandemic on the city’s once-bustling downtown.

What happens to the big businesses — whether they leave, stay, change their work-from-home policies — will affect the small ones, too.

Alicia Villanueva, who owns Alicia’s Tamales Los Mayas, a tamale factory in Hayward, Calif., and Lynna Martinez, owner of Cuban Kitchen, a restaurant in San Mateo, Calif., both said that despite devastating drops in their revenue, they avoided laying off any employees because of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and other loans.

Both businesses relied heavily on catering to tech and other companies in the Bay Area.

“We had hundreds of clients, including Oracle, Facebook, Google and Comcast CMCSA, -0.88%, ” Martinez said. “We would do anywhere between 100 to 300 orders before we opened our doors at 11 a.m. Then in March and April, boom, 50% of our business was gone.”

The two women said they have had to adjust and make up the lost business however they can. Martinez said her catering business is probably a tenth of what it once was. Villanueva’s son is delivering tamales to a school district that’s more than 60 miles away.

“He’s waking up at 2 a.m. to get ready and deliver to Vacaville at 5 a.m.,” said Villanueva, who has 21 employees.

Martinez and her eight employees are relying more on referrals, and she’s now considering franchising.

“The pandemic forced us to target a wider, more dispersed base,” she said. “In some ways, this was a good challenge for me as a business owner who wanted to pursue the idea of having a franchise.”