This post was originally published on this site

While other European cities remain tightly locked down, Spain’s already less-restrictive capital Madrid was gifted another hour of freedom this week.

Headed by Isabel Díaz Ayuso, the region’s government shifted the curfew by an hour to 11 p.m. to 6 a.m., from a prior one that started at 10 p.m., with effect from Thursday. That is despite pleading from the country’s health minister Carolina Darias for regions to keep restrictions in place, as COVID-19 numbers remain high and hospitals are under pressure.

Like elsewhere, Spain’s overall cases are falling. Health ministry data from Thursday showed a 14-day COVID-19 incidence rate of 320 per 100,000 for the country, but over 456 for Madrid, making it the second-worst region behind Melilla. That is as the country slowly gets its vaccination program moving amid recent supply issues across Europe.

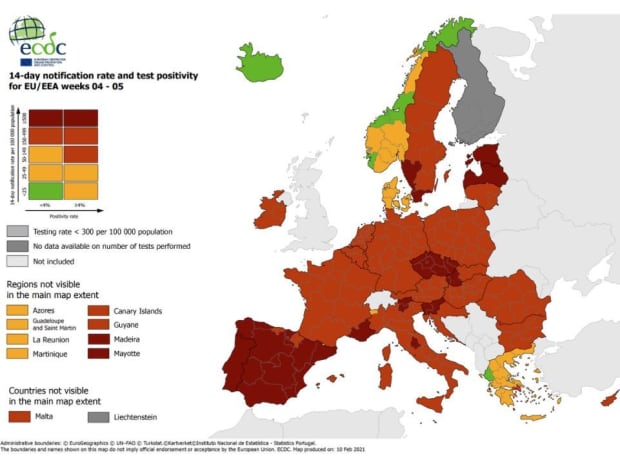

According to El País, Madrid’s infection rates are worse than many European cities, such as Paris, Brussels or Rome, and far higher than Berlin’s. (See the below Feb. 10 map from the European Union.) France keeps a 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. curfew in place, while Germany and the U.K. are only now starting to consider easing their own “hard lockdowns.”

As for what it looks like on the ground, a recent weekend in Madrid with springlike weather drew high demand for coveted outdoor tables. In the popular central La Latina district, there was a distinct night-before-Prohibition feel, as boisterous crowds rushed to cram in socializing before the 10 p.m. curfew.

With tourism absent, restaurant and bar owners here are desperate to make up for lost revenue, while locals seem just as eager to make up for lost living during the pandemic. It can also be hard to resist what everyone else is doing.

In a rare outing with friends last weekend, we walked an hour to find an empty outdoor table, then shifted indoors to a restaurant. Spain has had a strict mask policy since the summer, but they are not required while eating and drinking, and in this eatery, mask usage was sporadic among customers.

Read: UN chief joins WHO in slamming rich countries for hogging COVID vaccines

It was only afterward that we kicked ourselves a bit for taking such chances, as we discussed the contrast between full-of-life Madrid and the rest of Europe.

“We are learning to live with death,” said Oscar Durán, a friend who works in the film industry here. “We had hundreds of people dying a day, now it’s not as tragic or dramatic as the first wave.”

Madrid was one of the first wave’s early epicenters, with more than 900 people dying in a day at its peak. As Durán explained, western countries such as Spain choose to live with the virus and death, versus countries in Asia or New Zealand, which take strict measures and halt economies to preserve life and stamp out infections.

A busy Sunday in Madrid’s La Latina district on Feb. 14, 2021.

MARKETWATCH/KOLLMEYER

“We simply are accustomed to a certain number of people dying a day. Right now it seems OK that we have 300 deaths a day, because it’s less than 900,” said Durán. “Here in Madrid, with many deaths, people are arguing about whether bars should close at 10 p.m. or 11 p.m. And that seems crazy to people in countries such as Japan, Korea or New Zealand. For them, they want to avoid outbreaks and death.”

Daniel Sorando Ortín, a professor in the applied sociology department at the Complutense University of Madrid, acknowledged that Spain’s capital city is somewhat of a unique outlier.

“To start with, this is the place where more people died, both in absolute terms and in relative terms of the population, so it makes a difference. And being that, it is a region with less restrictions. And I think that the combination of a lot of this and very weak restrictions, it helps people to understand to live with it,” Ortín told MarketWatch in an interview.

The region’s premier Ayuso, who hails from the center-right People’s Party, is known for pushing back against tighter restrictions and nearly came to blows with the central government in October 2020. Her argument is that the economically hard-hit city needs to keep going.

Ortín recalled last May’s protests-by-car in the wealthier Madrid district of Salamanca, where participants railed against the government’s handling of the virus that including one of the world’s strictest lockdowns. At the time, he said, Ayuso’s response was that perhaps the whole of society shouldn’t stop for a small at-risk portion.

“It has a socioeconomic axis, because for example we know poor people have a higher likelihood than wealthy people, so wealthy people say ‘Don’t impose restrictions on us because we know how to handle it,’” he said, adding that it is the same for young people, especially those in more solid socioeconomic conditions, who also feel less at risk and don’t want to be as restricted.

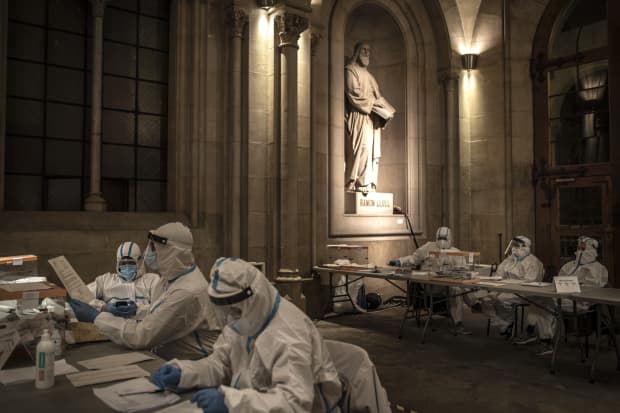

Election workers wear protective equipment during the final hour of regional Catalan elections voting, to allow those who are COVID-positive or who are in quarantine to cast their ballots, at Barcelona University on Feb. 14, 2021.

Getty Images

When you’re listening to the government constantly tell you that you shouldn’t stop eating or drinking or enjoying life, then it is easier to understand why people have “learned to live with deaths,” he said, though he added many in Madrid are struggling financially and not frequenting restaurants. Meanwhile, other Spanish regions are observing far tighter COVID-19 restrictions.

“For example, I have family in Aragon and La Rioja and the bars and restaurants are closed and you cannot enter into the city of Zaragoza. So the approach is so different institutionally, it has to have effects on the behavior of people, in my point of view,” Ortín said.

As for the virus itself, Madrid will still be dealing with increased transmission by new variants, such as the U.K. one that now accounts for one in five infections in across Spain, Dr. Vicente Soriano, director of the UNIR Medical Center in Madrid, clinician and professor of infectious diseases at the UNIR Health Sciences School & Medical Center told MarketWatch.

“The virus is moving to endemicity and it seems that is here to stay for a while to become endemic, as the other four human coronaviruses that cause winter colds. Re-infections with less severity will become the rule. It would take two to three years,” said Soriano.