This post was originally published on this site

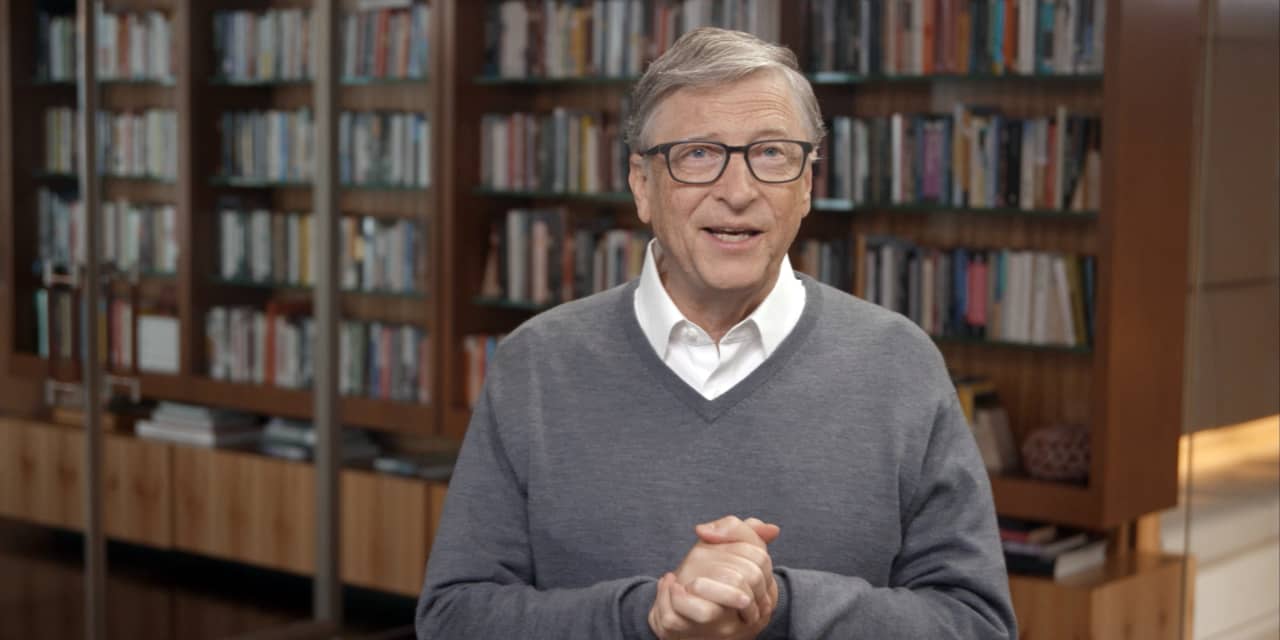

Bill Gates, “an imperfect messenger on climate change” by his own words, is enlisting action from a wobbly soap box.

The Microsoft MSFT, -0.53% founder pushes beyond seemingly small steps (putting an electric vehicle in the garage on the next trade-in) to embrace large, multinational moves (snatching carbon from the sky with technology in which he has a stake) in his new book, “How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need,” out Tuesday.

“I can’t deny being a rich guy with an opinion,” writes Gates, whose personal wealth rings up at more than $100 billion and whose “Xanado 2.0” mansion outside Seattle is but one address among several in his personal real estate portfolio.

One recent study finds that billionaires have carbon footprints that can be thousands of times higher than those of average Americans, largely because of transportation choices, including private jets like the one Gates uses. Gates was considered a bigger violator than Elon Musk TSLA, -2.44%.

Yet Gates has the power the wealthy wield to reverse some of his actions. In 2020 he started using sustainable jet fuel and “will fully offset my family’s aviation emissions in 2021,” the book details. And he has put money into solar technology and more already.

His call for rich nations to give up real beef may have brought the billionaire the greatest grief on social media as his book promotion geared up.

But the Gates hardcover has gotten serious attention yet again from major media outlets, one of which, The Guardian, pits the print endeavor from the long-time devotee to health issues against a recently published call to action from Michael Mann. Mann is arguably the world’s best-known climate scientist.

Mann, in his “The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet,” even called out Bill and Melinda Gates and their 2016 annual letter. Their letter at that time rang a more desperate alarm (“We need an energy miracle”) than a pragmatic how-to. Gates had also long resisted divesting from oil, at one time underplaying its effectiveness and later lamenting how hard it was to completely be fossil-fuel free. The new book says that divestiture has happened.

For Mann, his new war takes aim at “inactivists” or those he believes are using new tactics of “deception, distraction and delay” to prevent the phase-out of fossil fuels.

Gates doesn’t qualify for such a label, if his own words and the comity most reviewers are showing are to be believed.

Bob Ward, policy and communications director at the Grantham Research Institute on climate change and the environment at the London School of Economics and Political Science, commended how Gates views alternative energy.

“A key device used by Gates is to calculate the cost of clean alternatives relative to fossil fuels, and where they are currently more expensive, to quantify the difference as a ‘green premium,’” Ward wrote. “He then explains how this premium can be reduced through innovation and government policies. The credibility of the strategy is strengthened by references throughout to technologies in which Gates is investing his own money, such as novel ways to capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and then store it.”

And a WSJ Magazine profile of the author stresses the point that Gates believes approaches to date just won’t be enough — and he’s to be commended for moving the goal posts.

According to the magazine, the crux of the Gates’ argument is that, as helpful as innovations like electric cars, solar panels, lithium-ion batteries and plant-based burgers are to the effort, they don’t go far enough. There isn’t enough land on earth to plant enough trees to offset our carbon dependency.

“The key point in my book is that a serious climate plan — which we don’t have yet — involves counting in your head all the different sources of emissions,” Gates tells the magazine.

What’s next must go beyond agriculture and electricity to encompass all carbon-spewing processes (transportation, concrete and steel production) so that we can develop green alternatives. So, for example, Gates believes we must invent green steel.

The Nation, however, believes that a super emitter does not a climate warrior make.

“The billionaire’s new book, a bid to be taken seriously as a climate campaigner, has attracted the usual worshipful coverage,” writes Tim Schwab for the publication.

The author has investigated previously what he alleges is “self dealing” in the Gates Foundation as it works on health initiatives and other efforts in the developing world.

“The precarity of Gates’ position in the climate change debate [is] not just because of his thin credentials, untested solutions and stunning financial conflicts of interest,” Schwab wrote, “but because his undemocratic assertion of power — no one appointed or elected him as the world’s new climate czar — comes at precisely the time when democratic institutions have become essential to solving climate change.”