This post was originally published on this site

Higher interest rates are not the threat to the U.S. stock market that investors think they are.

This should come as a relief, since U.S. rates are up markedly in recent months. The 10-year Treasury yield TNX, -0.26% currently stands at 1.16%, more than double the 0.52% it yielded early last August. The 30-year Treasury just rose above 2% for the first time in a year.

The reason not to worry: Try as I might, I can find no statistically significant correlation between interest rates and the stock market’s subsequent return. I analyzed U.S. stock market history back to 1871. For each month over this 150-year period, I measured the S&P 500’s SPX, +0.04% inflation- and dividend-adjusted return over the subsequent 1, 5- and 10-year periods.

I was looking for a correlation between those returns and the 10-year yields at the beginning of the periods. I came up empty at the 95% confidence level that statisticians often use when determining if a pattern is real.

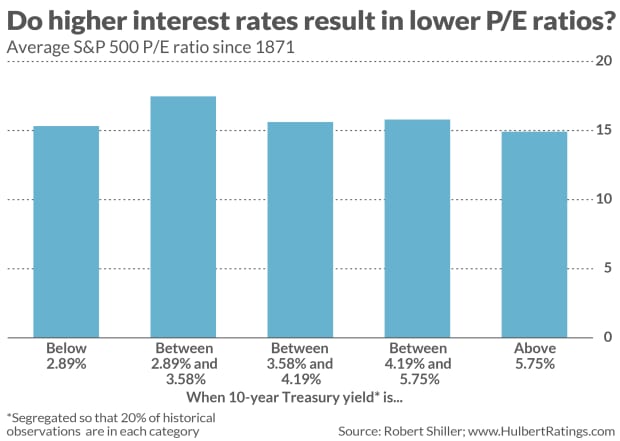

How, then, have so many investors come to believe that higher rates are bad for stocks? One reason is the notion that P/E ratios are inversely related to interest rates — that ratios are higher when rates are low, and vice versa. If this were true, of course, the recent uptick in rates would suggest that P/E ratios should decline. But this notion is not true, as you can see from the chart below. There is no correlation between interest rates and P/E ratio.

Another reason investors see higher rates as bad for stocks is the “competing assets” argument: Stocks face stiffer competition from bonds when yields are higher. According to this argument, the stock market will perform more poorly as interest rates rise.

Once again there is no historical support for this argument. To show this, I calculated the difference between the stock market’s earnings yield (the inverse of the P/E ratio) and the 10-year Treasury yield. If higher rates were bad for stocks, then we’d expect the market to perform more poorly when this difference was smaller (or negative). But this was not the case at the 95% confidence level.

Even more telling: Far from helping returns, including interest rates in a forecasting model hurts them. An investor’s track record when estimating the stock market’s subsequent return improves by ignoring interest rates and focusing on earnings yield alone, according to data covering the past 150 years.

Stock market currently is overvalued

Still, the U.S. stock market is overvalued right now. My point is that higher interest rates are not an additional reason to worry about stocks’ prospects.

If the stock market does struggle in coming weeks and months, no doubt higher interest rates will be blamed. Don’t believe it. Just as I argued last year that low interest rates do not justify higher valuations, the reverse is true too.

What has remained constant over the last several months, as interest rates have fluctuated, is that the stock market is significantly overvalued. That is what investors should be very worried about.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

Also read: The stock market is echoing 2009-10 — and that means a pullback could be near, analysts warn