This post was originally published on this site

Wall Street’s most popular stocks are like the cool kids who won popularity contests in high school.

Yet many researchers have found that the winners of those contests often end up living far more troubled lives than the rest of us. One famous study found that the coolest kids at age 13 had, by the time they reached 23, a 40% greater rate of alcohol and marijuana abuse and a 22% greater rate of adult criminal behavior.

The analogy between cool kids and cool stocks is closer than you might think. Researchers have found that on average, the shares of the most-popular companies lag those of the least-popular companies.

The reason to focus on these timeless truths now is that Fortune magazine has just released its latest annual ranking of the most admired companies in the U.S..

To be sure, the research into coolness focuses on the “average” kid and “average” stock. Sometimes a popular company will outperform the market, but that’s the exception, as has been the case with Apple AAPL, -0.17%. This is the 14th year in a row in which the company has been at the top of the Fortune ranking, and the performance of its stock has been spectacular. Since last year’s ranking, for example, Apple shares have gained a dividend-adjusted 72%, compared to 17.2% for the S&P 500 SPX, +0.05%.

True to form, though, shares of the other 19 of the 20 most-admired companies have lagged the market over the past 12 months. They gained an average of 13.6% — 3.6 percentage points below the S&P 500.

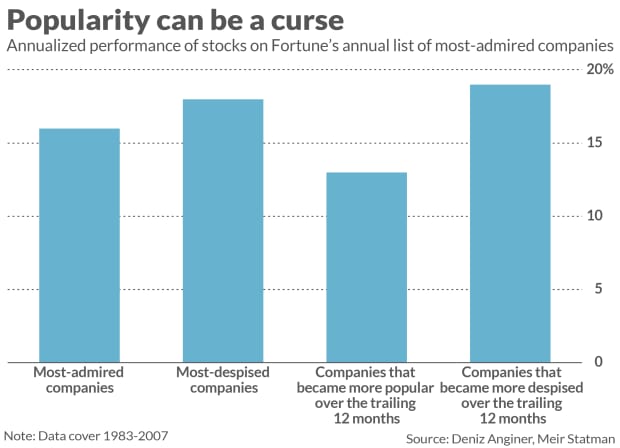

The message of more comprehensive data is similar, according to an academic study published a number of years ago by Deniz Anginer, an assistant finance professor at Canada’s Simon Fraser University, and Meir Statman, a finance professor at Santa Clara (Calif.) University. The professors constructed two hypothetical portfolios: The first contained the most admired companies in each year’s Fortune magazine ranking over a nearly 25-year period through 2007, while the second contained the companies that were most despised. They found that the despised-company portfolio outperformed the portfolio of admired company stocks by nearly two percentage points annualized.

An even more telling result emerged when the subsequent returns of stocks whose admiration score rose over a given year were compared with those of stocks whose score fell. The stocks in the former group underperformed those in the latter. (See the chart below.)

Cool factor is fleeting

One primary reason why popularity is an unreliable guide to picking stocks is that coolness is a fleeting attribute. Just take GameStop GME, -16.00%, which hardly any investors were focusing on a month ago. Then, almost overnight it seemed, the stock was up more than 20-fold from where it stood on New Year’s Day. People who have never bought a share of stock before were all of a sudden asking my opinion of whether they should buy.

For a fleeting moment, GameStop was the epitome of cool. Then, just as quickly, the stock lost its mojo and by the end of the first week of February, the shares were almost back to where they stood at the start the year.

As Warren Buffett, CEO of Berkshire Hathaway BRK.A, +1.19% BRK.B, +1.20%, has demonstrated with his phenomenal record, the stocks that produce the best long-term returns often are unglamorous workhorses, trudging away year after year producing consistent, if unspectacular, profits. Buffett’s railroad businesses come to mind, along with his longstanding investment in Coca-Cola KO, -0.17%. Such companies may not be cool, but they’ve produced impressive profits for investors over the years.

Why would unpopularity outperform popularity?

An unpopular company doesn’t have to be more profitable than a popular one in order for its stock to outperform. That’s because a stock’s performance is a function of investor expectations. A profitable company’s stock will perform poorly if its future profits fall short of investors’ expectations, just as an unprofitable company’s stock can perform well if its losses prove to be smaller than what investors had anticipated.

My favorite analogy to make this point is an imaginary 10-horse race in which any finisher pays off. Imagine further that the overwhelming favorite ends up coming in second, while the horse expected to come in a distant 10th finishes in 7th place. It’s conceivable that you would make more money betting on the horse that came in seventh than the one that came in second — even though the second-place horse was faster.

To illustrate what this means for some of today’s “coolest” stocks, consider Netflix NFLX, +2.67%, which commands a sky-high P/E ratio of 54.4 based on estimated earnings per share for the next 12 months. It’s a sobering exercise to calculate what Netflix’s return will be over the next three years, upon making two very reasonable — if not outright generous — assumptions:

- Earnings per share: We first must estimate what the company’s EPS will be in calendar 2024. FactSet is reporting that the consensus estimate from Wall Street analysts is that earnings then will be $21.81, up from $6.08 in 2020 and an estimated $9.85 in 2021. Analysts have a history of being too optimistic, but let’s assume they’re correct.

- P/E ratio: We next need to make an assumption about what the company’s forward-looking P/E ratio will be at the beginning of 2024. As companies grow and become larger, their P/E’s inevitably start to come back to earth. For purposes of discussion, let’s assume that Netflix’s P/E at the beginning of 2024 is 20% higher than the where the S&P 500’s forward-looking P/E now stands. Since the S&P 500 is currently trading at a much-higher-than-historical-average P/E, that’s a very generous assumption.

Given these two assumptions, Netflix’s return over the next three years will be 5.5% annualized. That’s half of the stock market’s long-term average return.

An even more sobering fate awaits other “cool” stocks. Under similar assumptions — relying on FactSet’s consensus EPS estimate and assuming a forward P/E 20% higher than the S&P 500’s — Amazon.com’s AMZN, -0.36% stock return over the next three years will be just 2.5% annualized. Tesla’s TSLA, -1.92%, meanwhile, will be minus 29.4% annualized.

Of course, if you try long and hard enough, you can torture either of these assumptions to produce a conclusion more to your liking. But you get the idea. Stocks that are trading for sky-high P/E ratios have to perform very, very well just to avoid losing money — much less beat the market.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: Is Tesla’s $1.5 billion bitcoin buy smart corporate finance? Experts weigh in