This post was originally published on this site

The $1.9 trillion coronavirus-aid package making its way through Congress is set to be the venue for a new debate between Democrats and Republicans — how best to get more money to families with children.

Democratic taxwriters in the House were set to unveil their plan Monday, ahead of an expected markup session later in the week of their portion of a bill that would go to the Senate and be immune to the 60-vote filibuster requirement.

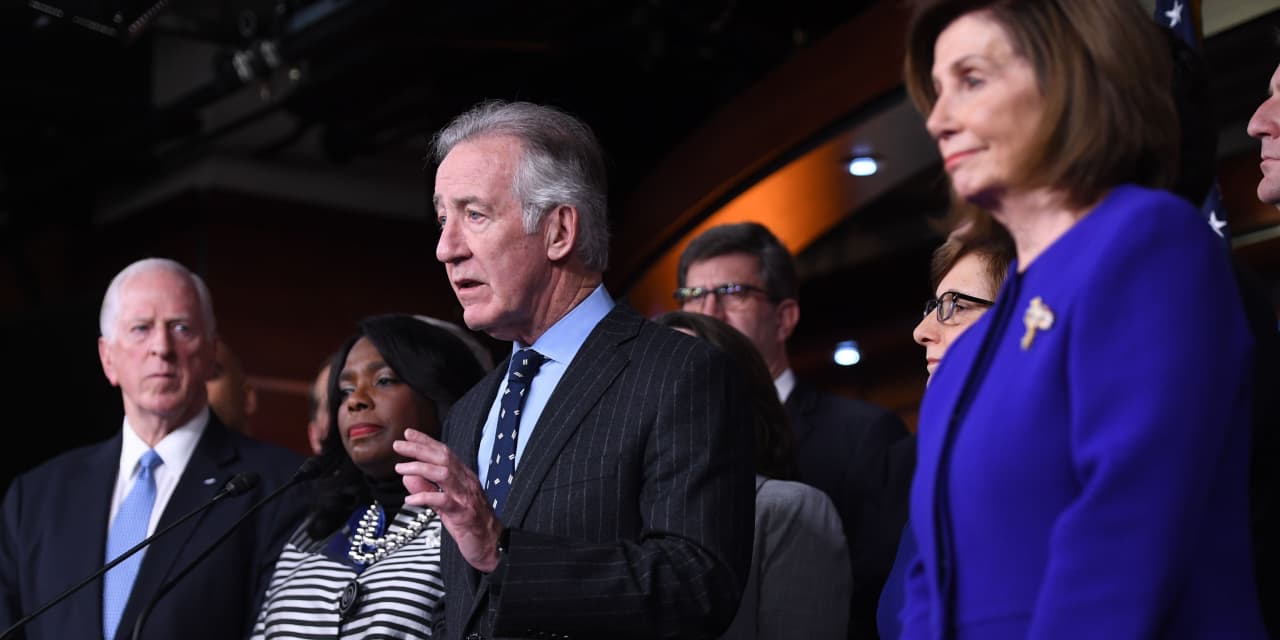

“The pandemic is driving families deeper and deeper into poverty, and it’s devastating. We are making the Child Tax Credit more generous, more accessible, and by paying it out monthly, this money is going to be the difference in a roof over someone’s head or food on their table,” said Rep. Richard Neal, a Democrat from Massachusetts.

Under draft legislative language obtained by MarketWatch.com, the Democrats’ plan would boost the $1,000 child tax credit currently in law for one year up to $3,000, or $3,600 in the case of families with children below 6 years old.

The credit would be refundable — meaning that if a family’s tax bill was bigger than the credit, they would still be eligible to receive it. The credit would begin to phase out at income levels of $75,000 for individuals and $150,000 for couples.

The liberal Economic Security Project praised the plan, saying, “Monthly direct payments are the quickest and most effective way to get help to families who need it.”

The Democratic proposal was unveiled only days after Sen. Mitt Romney, a Utah Republican, released his own proposal, which would also give money to families with children but instead use the Social Security Administration to cut the checks, not the Internal Revenue Service.

Under Romney’s proposal — which, unlike the Democrats’ plan, would be a permanent program — families would be eligible to receive a monthly benefit, starting during pregnancy. For children 5 and younger, the benefit would be $350 a month. From the ages of 6 to 17, the benefit would shrink to $250 a month.

Romney would offset the costs of his plan with a combination of cuts elsewhere in the budget. They would include eliminating the state and local taxes deduction, which was limited in the 2017 tax cut bill and Republicans say benefits the wealthy most. Other cuts would eliminate the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families government assistance program, the “head of household” tax status, and the existing child and dependent care tax credit.

“American families are facing greater financial strain, worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, and marriage and birth rates are at an all-time low. On top of that, we have not comprehensively reformed our family support system in nearly three decades, and our changing economy has left millions of families behind,” Romney said Thursday.

“Now is the time to renew our commitment to families to help them meet the challenges they face as they take on most important work any of us will ever do — raising our society’s children.”

Liam Donovan, a principal with Bracewell LLP’s Policy Resolution Group in Washington, said the fact the Democrats led their aid package rollout this week with details of the child tax credit boost shows they’re serious about it, and its chances for inclusion in a final package are good.

“It’s a longstanding priority,” he said. “In terms of the interplay with Romney, I think it’s almost kind of incidental, but in terms of their intentions here, they seem pretty clear this is a high priority.”

While the Democratic plan as proposed is temporary, history has demonstrated lawmakers’ willingness to extend popular temporary tax breaks when they are set to expire. That could make the proposal, for which the Democrats did not specify any offsetting cuts or revenue increases elsewhere, one of a group of provisions called “tax extenders” that are routinely given new life on an annual or biennial basis.

Donovan said that including the idea in the coronavirus bill and passing the bill through the budget reconciliation process, which means it can’t be blocked by Republicans in the Senate, shows how the tax code will reflect the political polarization of the times.

“So long as the only route to major legislation is through reconciliation, I think the tax code is going bear all the hallmarks of what it takes to get something done through reconciliation. It’s going to make it more complicated, but that’s just the nature of the beast at this political moment,” he said.