This post was originally published on this site

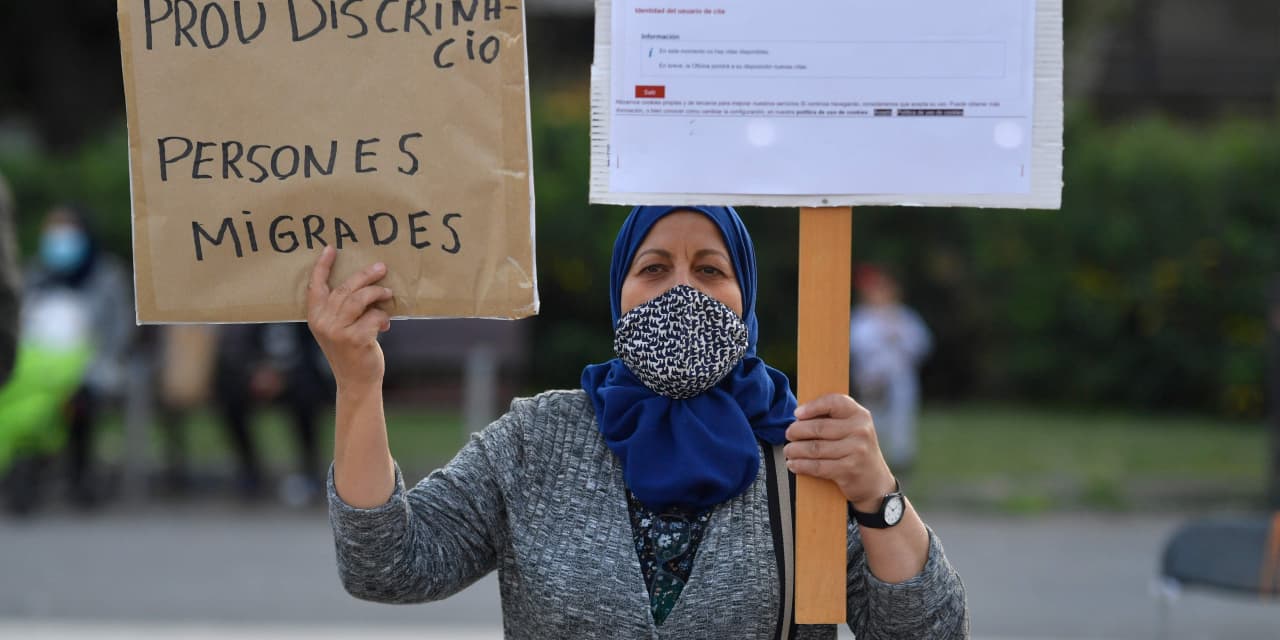

Undocumented immigrants in the U.S. will be a critical population to reach with COVID-19 vaccines, advocates and experts say, and public-health officials will first have to knock down barriers to access.

The issue came to the fore on Jan. 4 when Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts, a Republican, answered a question during a news conference about vaccinating undocumented workers in meat-processing plants. “You’re supposed to be a legal resident of the country to be able to be working in those plants, so I do not expect that illegal immigrants will be part of the vaccine with that program,” he said.

Ricketts spokesman Taylor Gage later clarified on Twitter TWTR, +3.64% that the governor had meant that undocumented immigrants “are not allowed to work in meat-processing facilities and therefore will not be receiving the vaccine in that context.” He added that while the federal government was expected to make vaccine doses available to everyone eventually, “Nebraska is going to prioritize citizens and legal residents ahead of illegal immigrants.”

(The term “illegal immigrants” is regarded as a slur by advocates of undocumented workers and others who argue that the term implies they are a criminal, say that a human being cannot be illegal, and advocate for the term “undocumented immigrants.”)

Reached for comment several days later, Gage told MarketWatch this prioritization plan remained the position of the governor’s office. But he also noted that “similar to other vaccines, proof of citizenship is not required to be vaccinated.” He did not respond to a question about how citizens and legal residents would receive higher vaccine prioritization if proof of citizenship wouldn’t be required.

The messaging from the governor’s office ran counter to public-health principles, said Darcy Tromanhauser, the director of the immigrants and communities program for the nonprofit Nebraska Appleseed — causing unnecessary confusion and undermining trust in immigrant communities after months of work preparing for effective vaccine outreach.

“On one hand, I don’t know that on a practical level [that] that’s even workable policy or that the authority would be there,” Tromanhauser said. “On the other hand, just saying it created damage.”

‘We cannot have any populations that are not vaccinated’

Alejandra, a Los Angeles resident who overstayed her visa in the U.S. more than two decades ago after two of her siblings were killed in Mexico, told MarketWatch through a Spanish-language interpreter that she believed it would be “very unfair” to prioritize vaccine access based on immigration status.

“Just because we’re undocumented does not mean we’re worth less than other people,” said Alejandra, whose full name MarketWatch is not publishing for privacy reasons. “I’ve been working in this country for 23 years; I’ve always followed the rules. … The only bad thing I’ve done is being here without any documentation.”

It doesn’t matter whether someone is documented or undocumented, successful or not, she added: “Our lives are worth the same.”

Some 10.5 million unauthorized immigrants lived in the U.S. as of 2017, the Pew Research Center estimates, making up about 23% of the foreign-born population.

The country’s roughly 22 million noncitizen immigrants — a group comprising both undocumented and lawfully present immigrants — have likely faced a number of exposure risks during the pandemic related to home, work and commuting, according to an analysis of 2018 data by the Kaiser Family Foundation, a health-care think tank. They may also have experienced financial strain from job loss and low income, as well as hurdles to testing and treatment access, the report said.

“ ‘They are the people growing our food, preparing our food, delivering our food, providing health care and providing transportation.’ ”

Noncitizen immigrants are more likely than citizens to reside in households with more than four people, live in urban areas and be uninsured, according to the Kaiser analysis.

Meanwhile, almost a quarter of the United States’ almost 13 million noncitizen workers have jobs in restaurant and food services and construction, industries hardly conducive to remote work; they make up substantial shares of agricultural workers (42%), housekeepers and maids (30%) and janitors and building cleaners (16%). They are also twice as likely as citizen workers to have a household income less than 200% of the federal poverty level, and before COVID-19, they were more likely to commute using public transit or carpools.

While official COVID-19 data doesn’t account for immigration status or country of birth, “the COVID-19 case rate and mortality among undocumented immigrants are undoubtedly much higher than they are in the general Latinx population,” Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine researchers wrote this month in a New England Journal of Medicine article. (People born in Mexico and Central America make up a majority of the U.S. undocumented population.)

“We know that the virus does not discriminate based on immigration status,” Samantha Artiga, a co-author of the Kaiser report, told MarketWatch. “In particular, noncitizen immigrants face a real set of increased risks and challenges associated with the virus and the pandemic: They are in working and living situations that put them at increased risk for exposure to the virus.”

This, she added, “points to the importance of ensuring that they have access to vaccines.”

Many noncitizen immigrants are at increased COVID-19 risk through their role in the essential workforce, Artiga added, “providing us continued access to the food and supplies we need throughout the pandemic.” In New York state, for example, nearly one-third of essential workers are foreign-born and 70% of the undocumented labor force is employed by essential businesses, according to a report by the Center for Migration Studies of New York, a pro-immigration think tank.

“It does not matter what someone’s immigration status is — it matters that they are the people growing our food, preparing our food, delivering our food, providing health care and providing transportation,” said Max Hadler, the director of health policy for the New York Immigration Coalition, a policy and advocacy organization.

Denying vaccination to undocumented immigrants would be wrong from not just a moral perspective but from a public-health standpoint, said Georges Benjamin, the executive director of the American Public Health Association.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Anthony Fauci has suggested, with some caveats about uncertainty, that between 75% and 85% of the U.S. population may need to be vaccinated against the disease to reach herd immunity.

“As a matter of good, sound public-health policy and protection, we cannot have any populations that are not vaccinated,” Benjamin told MarketWatch.

Some immigrants may feel ‘it’s safer to just avoid accessing programs or services’

Experts anticipate several challenges to vaccinating undocumented immigrants. Some pertain to access, Artiga said: Noncitizen immigrants are less likely to have existing connections with health-care providers, for example.

While the federal government has worked to provide free vaccine doses available to uninsured people regardless of immigration status, uninsured individuals may still worry about potential vaccine costs, and noncitizen immigrants may hit roadblocks in the form of “limited transportation options, lack of flexibility in work and child-care demands, and/or language and literacy challenges,” added a more recent Kaiser Family Foundation report co-authored by Artiga.

Noncitizen immigrants may also have greater concerns about vaccine side effects and their potential to impact their ability to work, the report said.

On top of access-related barriers, fear and uncertainty have spread through immigrant communities over the past few years, making people increasingly reluctant to access programs and services, Artiga said. Those fears include an undocumented person’s potential exposure to deportation or detention, she said, but also potential jeopardization of a person’s immigration status or ability to transition to lawful permanent resident status in the future.

Concerns extend broadly across immigrant families, and aren’t just limited to undocumented people or families with an undocumented individual, she added.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, sounded the alarm in December about a federal vaccine-distribution plan under which he said individuals’ identifying details could be collected and potentially shared with “multiple federal agencies,” warning that could discourage undocumented people from taking the vaccine. He later announced that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had amended their requirements such that the state wouldn’t provide any data that could be used to identify someone’s immigration status.

“ ‘Despite these limits on how the data may be used, the collection of personal data and sharing of it with the federal government will likely make some immigrant families more reluctant to access the vaccine.’ ”

The CDC’s vaccine data use and sharing agreement says “the use of vaccine administration data will be limited to completing work in furtherance of the public-health response to COVID-19,” and notes that vaccine recipients’ data may not be used “for any civil or criminal prosecution or enforcement, including, but not limited to, immigration enforcement.”

Still, the second Kaiser report noted: “Despite these limits on how the data may be used, the collection of personal data and sharing of it with the federal government will likely make some immigrant families more reluctant to access the vaccine.”

Many immigrants may also be concerned about the Trump administration’s public-charge rule, under which the U.S. government can deny Green Cards or visas to people it deems likely to become dependent on public benefits like food stamps or Medicaid. U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services have said they will not include COVID-19 testing, treatment or vaccines in public-charge determinations.

The country’s overall immigration-policy climate has made many immigrants increasingly uncertain about various rules and policies, Artiga added. “It is very confusing and complicated,” she said. “In many cases, people may not fully understand the full details of different policies and who is and is not affected — and may just feel like for them, it’s safer to just avoid accessing programs or services.”

Ran Harnevo, the CEO of the immigrant social-networking app Homeis, which has become a hub for COVID-19 resources during the pandemic, said he believed a key vaccine concern among some users was that their personal information could be used against them. Another is cost, despite the federal government’s vow to provide vaccine doses for free. “We saw a lot of people that are not going to get tested, because they’re not sure if they’ll get a bill at the end of the day,” he said.

See also: Should Black and Latino people get priority access to a COVID-19 vaccine?

Many immigrants have been unsure of whether they’re eligible for COVID-19 stimulus programs, Harnevo added, an uncertainty he believed could extend to vaccination.

Alejandra, a Homeis user, says “of course” she will take a vaccine once it’s available to her. Her chronic lung and heart problems, which put her at increased risk for COVID-19, have prevented her from working for the past two years because she has always held physically demanding jobs that involve carrying and lifting. “I believe in medicine and I believe in doctors,” she said.

But she also understands many undocumented residents’ aversion to interacting with medical and governmental institutions. “Generally, I’m well-informed, but there’s a lot of people that are not,” Alejandra added. “Even [some] people with documentation are not informed, so they’re still afraid.”

Reports suggest misinformation and scams may pose an additional barrier among immigrants and undocumented people. Alejandra, for example, said she had recently witnessed a man in her COVID-19 testing line purporting to sell a vaccine and “remedy” for large sums of money.

Support from the outgoing and incoming administrations

Some states, unlike Nebraska, have worked to address potential obstacles in vaccinating immigrants, Kaiser’s analysis showed: Arizona’s state health director said this month that the state’s undocumented population was high priority for vaccination, for example, and Illinois’ public-health department explicitly states that all populations, “including individuals who are undocumented, can receive the vaccine.”

Meanwhile, officials in Connecticut and Utah have assured residents that their personal information will be kept safe.

“ ‘As we go out to the broader population, we should leave no pockets of potential infection behind.’ ”

The CDC, the Department of Health and Human Services, and President Joe Biden’s team did not return MarketWatch requests for comment on whether they would issue specific guidance for prioritizing and distributing COVID-19 vaccines to undocumented people.

But Biden’s proposed $1.9 trillion COVID-19 stimulus plan notes that his administration will work to ensure everyone in the country, “regardless of their immigration status,” can receive the vaccine for free and without cost sharing. Biden will ensure “equitable distribution of vaccines and supples” for underserved communities, according to his blueprint.

“Every person in the country, whether they’re undocumented or documented, should have access to a vaccine, if and when it occurs,” he said in August.

The Trump administration’s surgeon general, Jerome Adams, also sought to assure undocumented residents in December that they would be able to get vaccinated.

“No one in this country should be denied a vaccine because of their documentation status, because it’s not ethically right to deny those individuals,” Adams said on CBS’s “Face the Nation.” “I want to reassure people that your information, when collected to get your second shot if you get the Pfizer PFE, -0.63% or Moderna MRNA, +0.10% vaccine, will not be used in any way, shape or form to harm you legally.”

Don’t miss: For some, Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID-19 rescue plan is a ‘lifeline’ — and wouldn’t come a moment too soon

How to make the vaccine accessible and address fears

Inoculating the country’s millions of undocumented residents will mean ensuring vaccination is available in locations and during hours that people can access it, making sure they know where and how to access it, and making clear that there are no associated costs, Artiga said.

This effort will involve “outreach programs where the vaccine comes to them or where they’re brought in to get the vaccine … recognizing that many communities of essential workers are not necessarily Monday-to-Friday, 9-to-5 availability,” Benjamin said. The vaccine needs to be accessible to shift workers and people without cars, he said.

Outreach will also mean providing materials in people’s first language, he added, as well as messengers “who represent their same ethnicity or culture, or at the very least speak their language quite well.”

In the short term, Artiga said, “messaging about who is eligible and that it cannot have negative impact on immigration status can be a key part of outreach.”

The Kaiser report also recommended “minimizing the collection of personally identifiable information, clearly explaining how it will be used, and clarifying that it cannot be used for immigration-related purposes.” The federal government has said it won’t use vaccination data for immigration enforcement or public-charge determinations, the report added, but “communicating this information directly to families through trusted messengers will be key” to assuaging concerns.

Vaccines without complicated storage logistics — the Pfizer-BioNTech BNTX, -1.40% product must be kept in expensive ultra-cold freezers — will be easier to administer in large settings like vaccine fairs to harder-to-find people, Benjamin added. That also applies to the forthcoming vaccine candidates that may require only one dose instead of two, like the highly anticipated Johnson & Johnson JNJ, -0.25% vaccine.

“As we go out to the broader population, we should leave no pockets of potential infection behind,” Benjamin said. “All that will result in is a tragic opportunity, and a risk for us all.”