This post was originally published on this site

One key to unlocking the logjam of COVID-19 vaccines is in plain view but so far overlooked: the neighborhood retail pharmacy.

As of Monday, 9 million people had received at least one dose of the Pfizer PFE, -0.14% or Moderna MRNA, -0.05% vaccines since they were approved in December. That is just a fraction of the more than 25 million doses that had been delivered to states and federal agencies in that same time.

Several factors are in play. Pfizer’s vaccine must be stored at minus 70 degrees Celsius which complicates inoculation efforts that are not close to specialty freezers. Moderna’s vaccine must also be stored in a freezer, but at a more manageable minus 20 degrees.

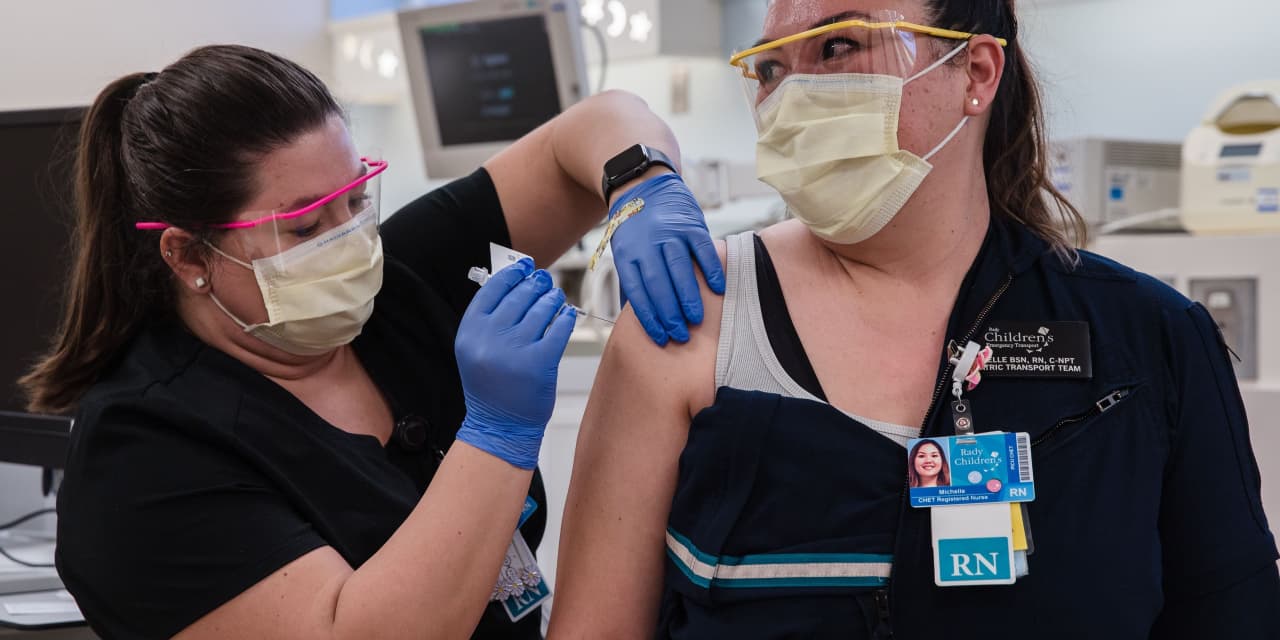

In addition, the Centers for Disease Control recommends that the shots be prioritized, with health-care workers first, which creates a welter of tiers, and categories within tiers, for public health agencies to manage.

Another protocol–that doses be held back to guarantee that second shots are available to complete vaccinations—may be eased once the Biden Administration takes office.

But perhaps most important, we need to get a better plan in place to involve independent pharmacies so that mass inoculations can ramp up more quickly.

The federal government contracted in November with the CVS CVS, +1.61% and Walgreen WBA, -0.81% chains (and some pharmacies in the Managed Health Care Associates organization) to provide vaccinations to long term care facilities. But CVS and Walgreens run only 18,400 of the 62,100 retail pharmacies operating in the U.S.

In recognition of the need for broader reach, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said on Jan. 7 that federal partnerships with 19 chains and associations would ultimately include 40,000 pharmacies.

Left out for the most part are the independent pharmacists, who are the single most accessible health providers to Americans. Thanks to independents that blanket the country, 90% of the population lives within 5 miles of a pharmacy.

West Virginia vs. California

Their efficiency and accessibility is already on display in the COVID-19 rollout. West Virginia, which does not have many chain stores, elected to use 250 independent pharmacies as the backbone of its vaccination drive. As a result, West Virginia is the top state so far in distributing initial shots among states that have received at least 100,000 doses. It has used 60% of its allocated vaccines to inoculate 5.4% of its population.

By comparison, the nation’s most populous state, California, has used only 28% of its allocation and has inoculated just 2% of the population. Los Angeles County, now the national epicenter of the pandemic and desperate to accelerate its vaccine distribution, is turning to pharmacies. It is planning to open 75 additional vaccination sites, up from 19. Seventy of those will be retail pharmacies.

In the battle against COVID-19, pharmacies have more advantages than just ubiquity and trained vaccinators. They are among the most trusted professionals in the country, according to the Gallup Poll, and therefore are in good position to help their communities overcome vaccine hesitancy.

They also are the most contacted health professionals for people with chronic conditions and therefore can act quickly to vaccinate clients when they come in for other medications. In many independent pharmacies, they know their clients well enough to be proactive in urging them to come in for a vaccination.

Chain and independent pharmacies are very similar in their vaccine workflow processes, including drive-through or parking lot-based injections, giving immunizations by appointment to limit foot traffic, and setting aside space for patients to wait to check for adverse reactions. Availability of a deep freezer may prevent some pharmacies from providing the Pfizer vaccine, but otherwise all other vaccines can be safely stored. Moreover, independent pharmacies tend to be less crowded than chain pharmacies, which may be an advantage.

An alternative strategy for expanding vaccinations—the use of large sites where thousands could come for shots—is not without risks. Initial shots need 10 days to muster an immune response, so such sites have the potential to turn into disease spreaders rather than preventers.

Marshalling pharmacies is not a perfect solution. Many neighborhoods in low-income urban areas are pharmacy deserts, where residents have to travel to get prescriptions filled. Officials will have to create mobile clinics and mount outreach drives to fill that gap.

But tapping pharmacies would allow public health departments to maximize efficiency and potential by utilizing existing infrastructure, freeing resources for harder-to-reach populations. In this early phase of the vaccination efforts, when we are in a race to build herd immunity and save lives, we can’t afford to ignore the role of a valued and trusted American institution, the corner pharmacy.

Vassilios Papadopoulos is dean of the School of Pharmacy at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.