This post was originally published on this site

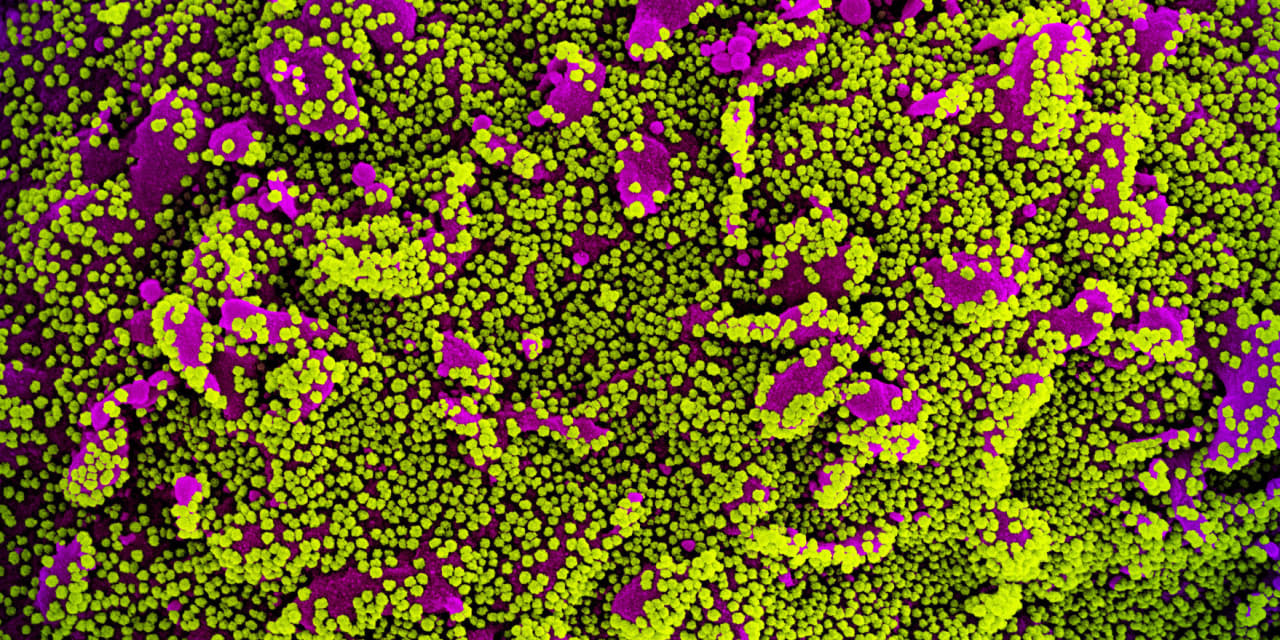

The United Kingdom’s use of genomic sequencing to identify a more infectious strain of SARS-CoV-2 has largely served as a wake-up call for inadequate use of the technology in the U.S.

Up until mid-December, the U.S. had sequenced about 0.3% of its COVID-19 samples, a percentage that is significantly lower than other developed countries despite the fact that it has one-fourth of the world’s cases.

In comparison, the U.K. is sequencing about 10% of its samples, and Australia aims to real-time sequence all of the relatively limited number of positive COVID-19 tests there.

“The U.S. has been a no-show for sequencing if you look at the world stage,” said Dr. Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute. “Sequencing gives us many different things. It tells us how the virus is moving from place to place. It tells us how fast it’s changing. We can say it was here on this day, and it was there another day. It can tell a super-spreader.”

See also: Here’s what we know so far about the new strain of COVID-19

Growing concern about “hyper-transmissable” new strains of SARS-COV-2 has raised more awareness about the nation’s lack of federal funding and development of the kind of genomic surveillance that helped the U.K. identify the B.1.1.7 strain and South Africa pinpoint the B. 1.351 strain in December. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Friday it’s likely that B.1.1.7 will become the most dominant form of the virus in the U.S. by March.

“We simply do not have the kind of robust surveillance capabilities that we need to track outbreaks and mutations,” President-elect Joe Biden said Thursday, when he called for a dramatic boost in genomic sequencing and surveillance as part of his proposed $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan.

While a good chunk of federal pandemic dollars have gone so far toward immediate needs like testing, contact tracing, and helping drugmakers scale up their vaccine manufacturing capabilities, experts are now pushing the U.S. to build a stronger genomic surveillance system that can help public-health departments identify new strains while also better addressing regional or community outbreaks.

All viruses evolve, and SARS-CoV-2 is thought to develop one to two variants a month, though it mutates much more slowly than the flu virus. Back in mid-2020, researchers began talking about the 614G mutation, which is now considered the dominant form of the virus worldwide. Now, concern has shifted to the B.1.1.7 and B. 1.351 strains, which are both thought to be more infectious.

The B.1.1.7 strain from the U.K. has been detected in at least 76 people in 12 states, as of Jan. 13, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (The B. 1.351 strain from South Africa has not been identified in the U.S. at this time.)

In the U.S., where rates of infections, hospitalizations, and deaths continue to soar, there has been less emphasis on population-level public health initiatives when testing and care remain in such high demand.

Read: Biden plans to distribute COVID-19 vaccine doses immediately

Intermountain Healthcare, a hospital system based in Salt Lake City, sent off all positive COVID-19 tests for sequencing in the early days of the pandemic. But when cases began to rise, and workload increased, the process began too disruptive and time-consuming, and it was stopped, said Dr. Bert Lopansri, chief of Intermountain’s Division of Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology.

“With increasing treatment options, vaccine rollout and emergence of novel variants, scaling up sequencing is critical going forward,” he said in an email.

If the U.S. sequenced at least 5% of positive COVID-19 tests, then it would be able to detect emerging strains or variants when they make up less than 1% of total positive cases, according to a model developed by the sequencing company Illumina Inc. ILMN, +1.43%. (Their model is set to be published this weekend as a preprint, a type of preliminary medical study.)

This would cost less than $500 million in 2021, according to Dr. Phil Febbo, the company’s chief medical officer.

Experts say that putting money behind a national genomic sequencing surveillance network cannot only help identify new variants in the future, it could aid overworked public-health departments with giving priority to who should get tested, contact traced, and isolated.

It could also be used to inform vaccine makers if there is “a vaccine escape strain,” a strain of the virus that could render currently available vaccines less effective or ineffective.

(A study conducted in a lab in mice by BioNTech SE BNTX, -4.02% and Pfizer Inc. PFE, -0.14% showed that their vaccine is still effective against the new strains, according to the Jan. 7 preprint. Moderna Inc. MRNA, -0.05% has also said it’s confident its MRNA vaccine will work against the U.K. strain)

“When they see a small cluster of a new variant come into a community, they can react quickly,” Febbo said, “and they can raise awareness to those who are infected and make sure that they do their best efforts to contain that.”

See also: FDA identifies 3 COVID-19 tests that may be impacted by new variant

Earlier this month, Illumina announced plans with a privately held testing company called Helix OpCo to develop a CDC-backed national sequencing surveillance system. Helix looks for samples from positive COVID-19 tests with the “S gene dropout” for Illumina to sequence. So far, they’ve ID’ed at least 51 cases of B.1.1.7. in the U.S.

Incorporating genomic sequencing into national surveillance isn’t the only way to modernize the way the U.S. can track and take action against the virus. Beyond testing, contact tracing, and isolating, this could include genomic sequencing, monitoring wastewater, gathering mobility data, and using digital sensors, according to Topol.

“As we get vaccines out there at full tilt, we’re going to start seeing containment of the virus,” he said. “And then there’s going to be places that are like whack-a-mole, where the virus tends to crop up again. If you’re sequencing, doing wastewater, digital, mobility, you basically have a real time dashboard in the country, and you see that, ‘Oh, wow, Kalamazoo is lighting up.’”

Illumina shares have gained 18% in the last 12 months, while the SPDR S&P Biotech ETF XBI, -1.11% has gained 59% and the S&P 500 SPX, -0.72% has gained 15%.