This post was originally published on this site

The coronavirus situation in the U.K. is far more pervasive now than in March when the country first locked down.

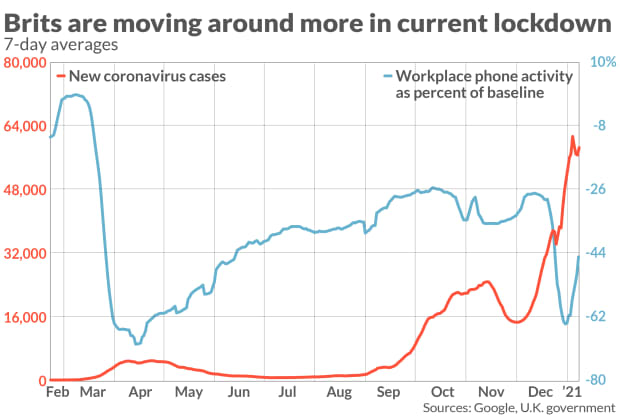

When U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced the country’s first lockdown on Mar. 23, 2020, there were 967 new cases. Even in the two months that followed, the highest daily new case reading was 6,201. When Johnson again addressed the nation on a new lockdown, on Jan. 4, 2021, there were 58,784 cases.

It is fair to note that the situation isn’t 10 times worse — hospitalizations are up about 10% from the worst levels of April, and deaths are slightly lower, reflecting the younger mix of new coronavirus patients as well as better treatment. But experts are warning that the peak in hospitalizations is still to come, with the National Health Service examining how to discharge patients into hotels to free up beds.

But faced with at least as bad a situation as March, Brits are out and about.

That is clearly seen in the mobility data. In the days after the Mar. 23 lockdown, mobile phone traffic around workplaces fell as much as 70%, according to Google. In the days after the Jan. 4 lockdown, mobile phone activity around workplaces is down about 50% from normal levels.

Car use, down to as low as 23% of normal levels after the March lockdown, was 56% of normal levels on Monday, according to the U.K. Department for Transport. On the London Underground, activity was 16% of normal levels, which doesn’t sound like much except when compared with the roughly 5% usage after the March lockdown.

Andrew Goodwin, chief U.K. economist at Oxford Economics, said current rules are in many cases weaker now than they used to be. The housing market, for example, is now able to operate pretty much as normal, while it was closed last year.

“In addition, firms have become much more adaptable,” said Goodwin. “Last March, many firms across sectors such as manufacturing and construction closed down, partly because the government messaging around what was and wasn’t permitted was not very clear and they adopted a cautious approach. But this time around they have been able to demonstrate they comply with the government’s COVID-safe rules and, because their workers cannot work from home, many have remained open.”

The U.K. government’s definition of key worker has changed, which is significant because those workers are allowed to put their children into schools. Some schools have up to 50% of their classrooms filled, according to U.K. press reports.

A construction worker uses a spade to remove mud from the tracks of a vehicle as work continues near Ashford in Kent, southeast England on Dec. 17, 2020.

ben stansall/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

David Owen, European economist at Jefferies, echoed that view that the change in mobility is a function of different rules rather than weak adherence to them. “There seems to be pretty much adherence to the rules,” he said. “Where I live in southwest London, there’s not that many people around. People seem to be much more concerned about being close to other people.”

There is hope on the horizon, as the U.K. is so far leading all but a handful of countries in vaccinations. “I’m sure for a lot of people, what they don’t want to do over the next few weeks [while waiting to get vaccinated] is actually catch the thing,” Owen said.

This increased activity should mean the U.K. economy will be stronger than it was in April 2020. Deutsche Bank is forecasting a 1.4% downturn in U.K. gross domestic product in the first quarter, which isn’t nearly as steep as the 19.8% nosedive in the second quarter of 2020, though that is off a base that is about 7% lower than it was before the COVID-19 pandemic.